The overarching goal of any action, which could also include stepped-up counter cyber espionage efforts, would be to create an effective deterrence and diminish the potency of future Russian cyber spying, the person said.

The unfolding crisis – and the lack of visibility over the extent of the infiltration into the computer networks of federal agencies including the Treasury, Energy and Commerce Departments – will push to the front of Biden’s agenda when he takes office on Jan. 20.

President Donald Trump only acknowledged the hacking on Saturday almost a week after it surfaced, downplaying its importance and questioning whether the Russians were to blame.

The discussions among Biden’s advisers are theoretical at this point and will need to be refined once they are in office and have full view of U.S. capabilities.

Biden’s team will also need a better grasp of U.S. intelligence about the cyber breach before making any decisions, one of the people familiar with his deliberations said. Biden’s access to presidential intelligence briefings was delayed until about three weeks ago as Trump disputed the Nov. 3 election results.

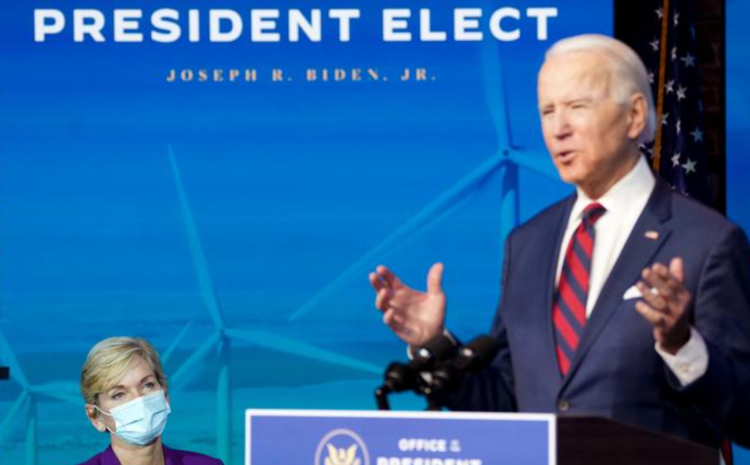

“They’ll be held accountable,” Biden said in an interview broadcast on CBS on Thursday when asked about how he would deal with the Russian-led hack. He vowed to impose “financial repercussions” on “individuals as well as entities.”

TEST OF WORKING WITH ALLIES

The response could be an early test of the president-elect’s promise to cooperate and consult more effectively with U.S. allies, as some proposals likely to be put before Biden could hit the financial interests or infrastructure of countries friendly to the United States, a person familiar with the matter said.

“Symbolic won’t do it” for any U.S. response, said James Andrew Lewis, a cyber security expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington think tank. “You want the Russians to know we’re pushing back”

A spokeswoman for Biden’s transition team did not respond to a request for comment.

Moscow has denied involvement.

One potential target for U.S. Treasury financial sanctions would be the SVR, said Edward Fishman, an Atlantic Council fellow who worked on Russia sanctions at the State Department during the Obama administration.

Media reports have suggested the SVR-linked hacking group known as “Cozy Bear” or APT29 was responsible for the attacks. The United States, Britain and Canada in July accused here “Cozy Bear” of trying to steal COVID-19 vaccine and treatment research from drug companies and academic institutions.

“I would think, at the bare minimum, imposing sanctions against the SVR would be something that the U.S. government should consider,” Fishman said, noting that the move would be largely symbolic and not have a major economic impact. The U.S. Treasury has already imposed financial sanctions on other Russian security services, the FSB and the GRU.

Financial sanctions against Russian state companies and the business empires of Russian oligarchs linked to Russian President Vladimir Putin may be more effective, as they would deny access to dollar transactions, both Fishman and Lewis said.

Those targets could include aluminum giant Rusal, which saw U.S. sanctions lifted in 2018 after blacklisted Russian billionaire Oleg Deripaska reduced his stake to a minority in a deal with the Treasury.

Lewis said a stronger option could be to cut Russia off from the SWIFT international bank transfer and financial messaging system, a crippling move that would prevent Russian companies from processing payments to and from foreign customers.

Such a move was contemplated in 2014 when Russia annexed Ukraine’s Crimean peninsula, but it would hurt the Russian energy sector, complicating gas sales to Europe and hit European companies with Russian operations.

Neither the Treasury nor State Department responded to questions about possible actions in response to the hacking.

The Pentagon’s U.S. Cyber Command likely has options for counter actions that could cripple Russian technology infrastructure, such as disrupting phone networks or denial of internet actions, Lewis said, adding that this too could hurt European allies.

“They’ll need to think through the diplomacy of that,” Lewis said.

The hackers likely left behind some malicious code that would let them access U.S. systems for retaliation against any U.S. cyber attack and it will take months to find and eliminate those “Easter eggs,” he added.

Reporting by Trevor Hunnicutt in Wilmington and David Lawder and Daphne Psaledakis in Washington; Writing by David Lawder; Editing by Mary Milliken and Daniel Wallis

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles