REUTERS image captionThe 737 Max was cleared to fly again late last year, after being grounded since March 2019

Boeing has agreed to pay $2.5bn (£1.8bn) to settle US criminal charges that it hid information from safety officials about the design of its 737 Max planes.

The US Justice Department said the firm chose “profit over candour”, impeding oversight of the planes, which were involved in two deadly crashes.

About $500m will go to families of the 346 people killed in the tragedies.

Boeing said the agreement acknowledged how the firm “fell short”.

Boeing chief executive David Calhoun said: “I firmly believe that entering into this resolution is the right thing for us to do – a step that appropriately acknowledges how we fell short of our values and expectations.

“This resolution is a serious reminder to all of us of how critical our obligation of transparency to regulators is, and the consequences that our company can face if any one of us falls short of those expectations.”

‘Fraudulent and deceptive conduct’

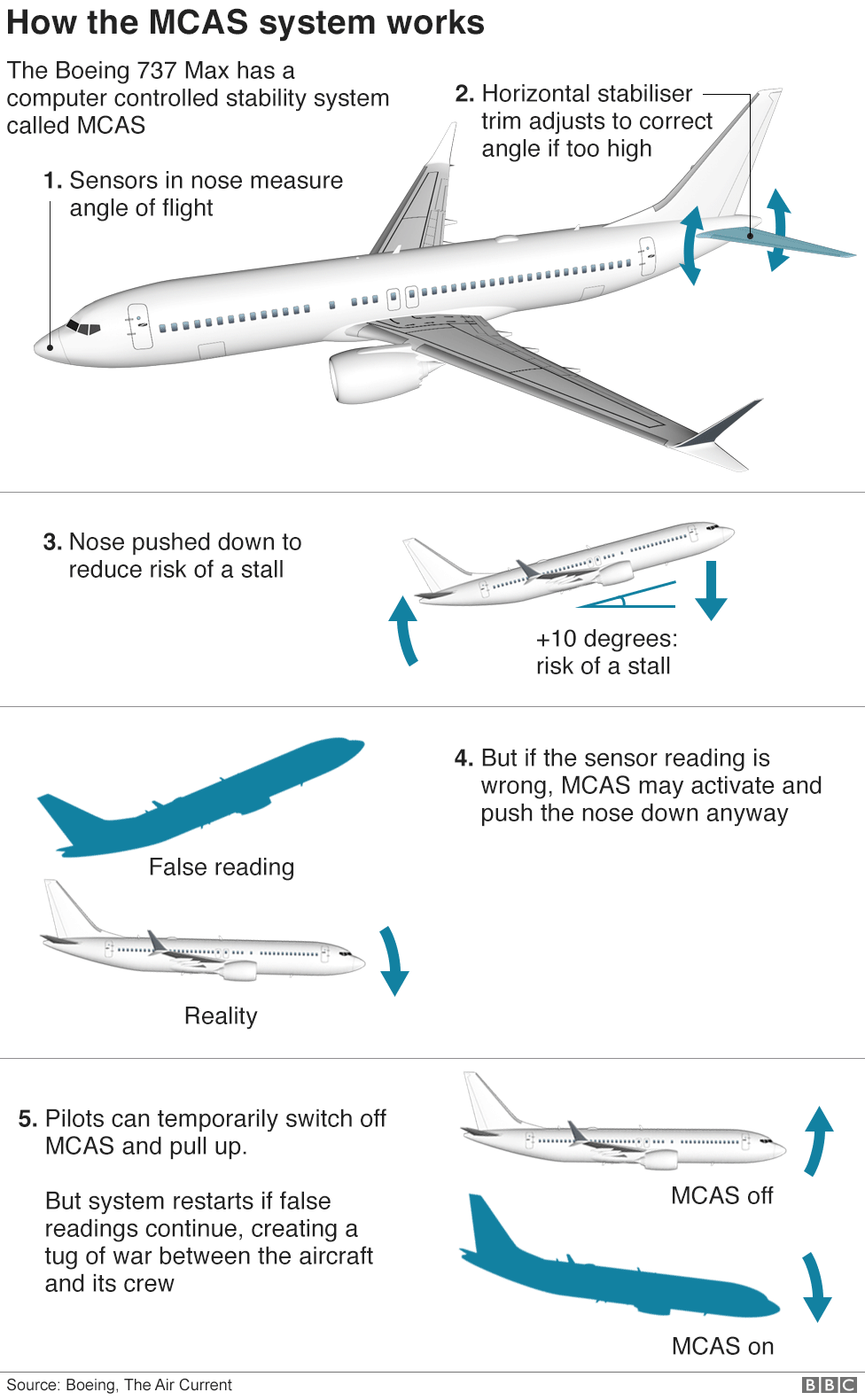

The Justice Department said Boeing officials had concealed information about changes to an automated flight control system, known as MCAS, which investigations have tied to the crashes in Indonesia and Ethiopia in 2018 and 2019.

The decision meant that pilot training manuals lacked information about the system, which overrode pilot commands based on faulty data, forcing the planes to nosedive shortly after take-off.

Boeing did not co-operate with investigators for six months, the DOJ said.

“The tragic crashes of Lion Air Flight 610 and Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 exposed fraudulent and deceptive conduct by employees of one of the world’s leading commercial airplane manufacturers,” said Acting Assistant Attorney General David Burns.

“Boeing’s employees chose the path of profit over candour by concealing material information from the FAA concerning the operation of its 737 Max airplane and engaging in an effort to cover up their deception.”

Under the terms of the agreement, Boeing was charged with one count of conspiracy to defraud the US, which will be dismissed after three years if the firm continues to comply with the deal.

Of the total settlement, the majority – $1.77bn, some of which has already been paid – is due to go the firm’s airline customers, who were affected by the grounding of the planes following the crashes.

The firm also agreed to pay a penalty of $243.6m.

But attorneys for the victims of the Ethiopian Airlines crash said the deal on Thursday would not end their pending civil lawsuit against Boeing.

“The allegations in the deferred prosecution agreement are just the tip of the iceberg of Boeing’s wrongdoing — a corporation that pays billions of dollars to avoid criminal liability while stonewalling and fighting the families in court,” said a statement from the group of lawyers representing them.

They added that the FAA “should not have allowed the 737 Max to return to service until all of the airplane’s deficiencies are addressed and it has undergone transparent and independent safety reviews.”

Boeing says it has now addressed concerns about the Max, while the plane returned to service in the US in December.

‘Scrutiny unlikely to stop here’

The charge against Boeing was that its employees used “misleading statements, half truths and omissions” to dupe the regulator charged with maintaining the safety of US aviation.

In the circumstances, you could say the company got off relatively lightly.

It has avoided prosecution, and a large part of the settlement involves compensation to airlines – a fair amount of which it would probably have ended up paying anyway.

The company would doubtless like to use this moment to draw a line under one of the most traumatic episodes in its history.

Yet while the 737 Max is back in the air, the scrutiny of Boeing and the FAA is unlikely to stop here.

Critics, including victims’ families, lawyers and politicians, insist serious questions about the aircraft remain – and they’re still pushing for answers.