IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGES

The vast territory, which belongs to Denmark but is autonomous, lies between North America and Europe and has a population of just 56,000.

Greenland’s economy relies on fishing and Danish subsidies, but melting ice and a planned mine could change the course of the vote – and the territory’s future.

Here’s what you need to know.

What’s at stake

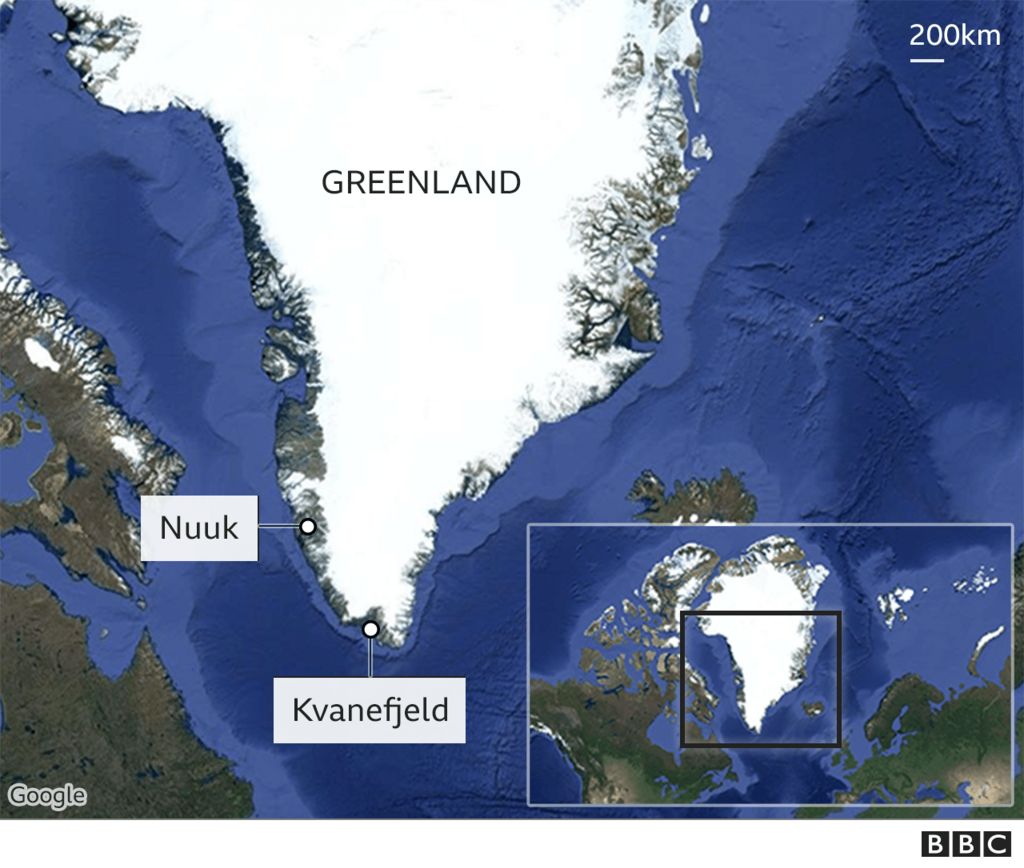

Disagreement over a controversial mining project in the south of Greenland has split the government and paved the way for this week’s election.

The company that owns the site at Kvanefjeld says the mine has “the potential to become the most significant western world producer of rare earths”, a group of 17 elements used to manufacture electronics and weapons.

The Siumut (Forward) Party supports the development, arguing that it would provide hundreds of jobs and generate hundreds of millions of dollars annually over several decades, which could lead to greater independence from Denmark.

But the opposition Inuit Ataqatigiit (Community of the People) party has rejected the proposal, amid concerns about the potential for radioactive pollution and toxic waste.

The future of the Kvanefjeld mine is significant for a number of countries – the site is owned by an Australian company, Greenland Minerals, which is in turn backed by a Chinese company.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GREENLAND MINERALS LTD/HANDOUT VIA REUTERS

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GREENLAND MINERALS LTD/HANDOUT VIA REUTERSWhy is Greenland important?

Greenland has hit the headlines several times in recent years, with then-President Donald Trump suggesting in 2019 that the US could buy the territory.

Denmark quickly dismissed the idea as “absurd”, but international interest in the territory’s future has continued.

China already has mining deals with Greenland, while the US – which has a key Cold War-era air base at Thule – has offered millions in aid.

Denmark has itself acknowledged the territory’s importance: in 2019 it placed Greenland at the top of its national security agenda for the first time.

And in March this year, one think tank concluded that the UK, the US, Australia, Canada and New Zealand – known collectively as the Five Eyes – should focus on Greenland to reduce their dependency on China for key mineral supplies.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT EPA

IMAGE COPYRIGHT EPAMining isn’t Greenland’s only issue, however.

The territory is on the front line of global warming, with scientists reporting record ice loss last year. This in turn has significant implications for low-lying coastal areas around the world.

But it is the retreating ice that has both increased mining opportunities and raised the possibility of new shipping lanes through the Arctic, which could reduce global shipping times.

This changing reality has also increased focus on long-running territorial disputes, with Denmark, Russia and Canada all seeking sovereignty over a vast underwater mountain range near the North Pole known as Lomonosov Ridge.