IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGES image caption Rajpath has been a huge draw for Delhi residents and tourists over the decades

By Geeta Pandey

BBC News, Delhi

The manicured lawns on either side of the wide ceremonial boulevard are a place for thousands to gather to soak up the winter sun or have an ice-cream on summer evenings.

But the 3km (1.8 mile)-long road, stretching from Rashtrapati Bhavan, the presidential palace, at one end to the India Gate war memorial at the other, now resembles a massive dust bowl.

The area is dotted with craters and mounds of earth – barricades stop people from getting close to men in reflective vests and yellow hard hats who are laying sewage pipes and tiled footpaths. A sign warns against taking photos and videos.

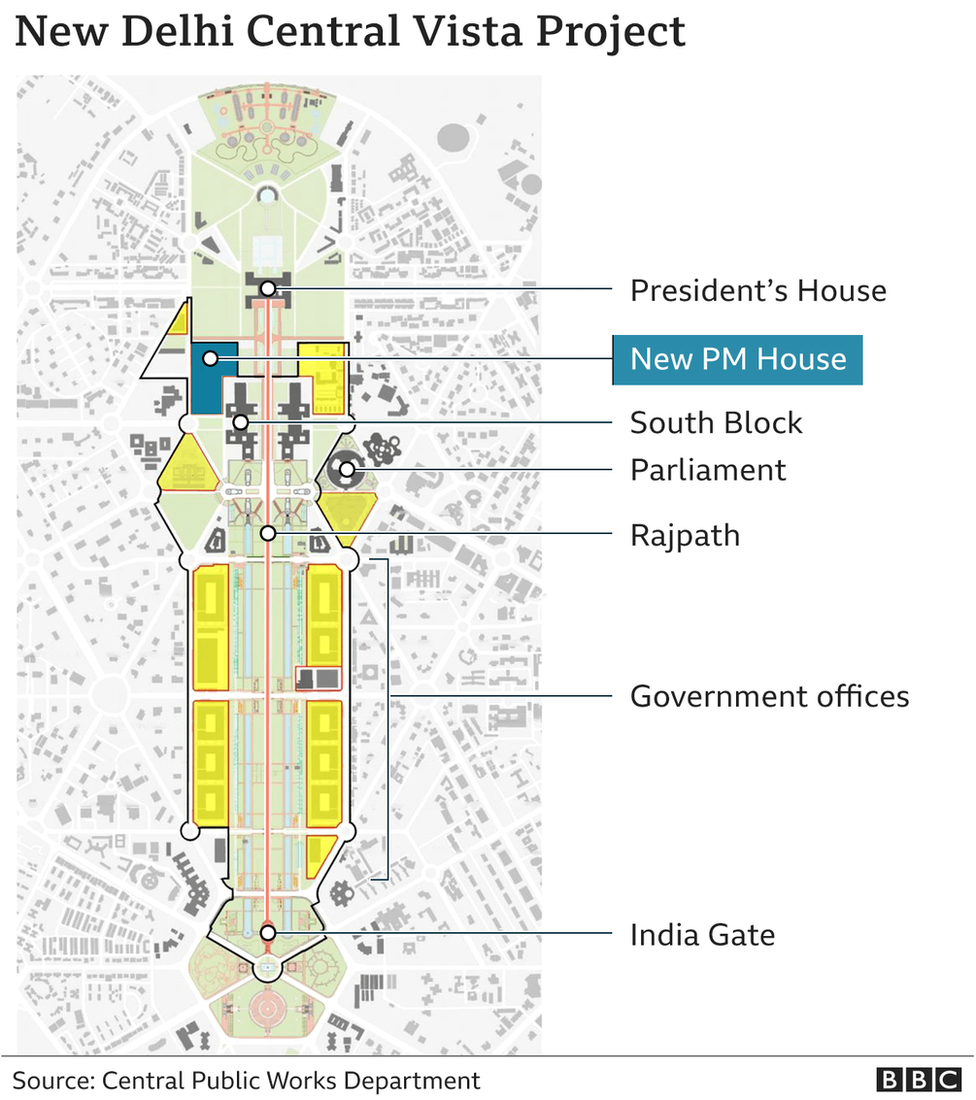

The work is part of the Central Vista project – a vast redevelopment plan that includes a new parliament, new homes for the vice-president and prime minister and multi-storey office blocks. It’s expected to cost upwards of 200bn rupees ($2.7bn; £2bn).

The project has been mired in controversy since it was announced in September 2019, with critics saying the money could be better spent on people’s welfare or cleaning up Delhi’s air, which is among the filthiest in the world.

Construction work is continuing even as India battles a devastating second wave of Covid-19, which has fuelled further public resentment. Critics have questioned Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s priorities, comparing him to “Nero fiddling while Rome burns“.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGESOpposition leader Rahul Gandhi has called it a “criminal waste” and urged Mr Modi to focus instead on dealing with the pandemic. In an open letter to Mr Modi, scholars criticised the project as an extravagant waste of resources “that could be used to save lives”.

Much scorn has been reserved in particular for the PM’s new house, due for completion by December 2022.

“This is pure escapism,” historian Narayani Gupta told the BBC. “At a time when the pandemic is killing thousands, crematoria are full and graveyards have run out of space, the government is building castles in the air.”

Where does the PM live now?

By all accounts, Mr Modi’s current accommodation is pretty fancy.

Besides the PM’s residential quarters, the complex has accommodation for guests, offices, meeting rooms, a theatre and a helipad. A few years ago, an underground tunnel was built to connect it to nearby Safdarjung airport.

“The Indian PM occupies an entire street – in Britain, 10 Downing Street is just a door with a number,” says Delhi-based architect Gautam Bhatia.

The property was chosen by Rajiv Gandhi in 1984. Intended to be temporary, it has been home to all Indian prime ministers ever since.

“Gandhi used three bungalows, the fourth and the fifth were added later on as the requirement to host more staff and security personnel grew,” says political analyst Mohan Guruswamy, a regular visitor over the years.

“It’s a relatively new construction,” says Gautam Bhatia. However, it has been repeatedly refurbished “at a great deal of expense”.

What do we know about the new house?

It will be centrally located in Delhi’s power corridor – between the Rashtrapati Bhavan at one end and the Supreme Court at the other, with parliament just across from the PM’s house.

According to government documents, the prime minister will occupy 10 four-storey buildings on a 15-acre plot between the president’s house and South Block, where offices of the PM and defence ministry are currently located. Rows of barracks built by the British in the 1940s and currently used as temporary offices will be demolished.

But further details about the residence are scarce. In an email to the BBC, project architect Bimal Patel’s office said “for security reasons we cannot share the details/blueprints with you”, refusing to say how much it would cost.

Architects, conservationists and environmentalists have criticised the authorities for a “lack of transparency”.

“There have been no proper public hearings and the project details keep evolving so there is no clarity,” said one architect, Anuj Srivastava.

Another, Madhav Raman, said building “such a massive structure” so close to South Block – a protected monument designed by leading 20th Century British architects Edwin Lutyens and Herbert Baker – was a cause for concern.

“The Archaeological Survey of India rules stipulate that there should be a minimum distance of 300m from a heritage structure but the new PM house will be just 30m away. There are also lots of trees on the plot, what will happen to them?”

So why does Mr Modi want to move?

Authorities say the PM’s present home is “not well-located”, is “difficult to secure” and needs “better infrastructure that is comfortable, efficient, easy to maintain and cost-effective”.

They say it should be located in “close proximity” to his office since road closures during his travels “cause major disruptions to city traffic”.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGESBut Mohan Guruswamy believes the new house has more to do with Mr Modi’s ambition.

“All real decision-making takes place in the PM’s house. He has a staff of hundreds and they clear 300 files a day.

“He has centralised power in his hands. He is creating a presidential form of government and he needs a bigger building – a White House or a Kremlin.”

Mr Guruswamy says Indian prime ministers have always lived in “buildings at the back”. But with his new home, Mr Modi wants to put himself in the centre of Delhi’s power corridor.

“But separation of power has to be physical too. He’s not just making a new home, he’s rearranging the institutions of government. Architecture changes the nature of power.”

What will happen to the Rajpath area?

Rajpath is a public space popular for recreation and also for protests and candle-light marches.

And even though the government insists that it will remain a public space, critics say it’s unlikely that large gatherings would be allowed because of the proximity to the PM’s house.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGESHistorian Narayani Gupta says the multi-storey office buildings, which will replace popular cultural centres like the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, the National Museum and the repository of our modern history, the National Archives, would overshadow India Gate and drive away people.

“They are moving rare manuscripts and fragile objects to temporary locations. How do we know that there won’t be any damage?”

Kanchi Kohli, of the think tank Centre for Policy Research, says land in Delhi is designated for specific purposes – such as recreational, semi-public or government – and authorities can’t just take over an area and change its use.

“This is a land grab.”

What is the government saying?

Minister for Urban Development Hardeep Singh Puri has defended the project.

Rejecting criticism of government priorities during the pandemic, he said the project cost was 200bn rupees over several years “while the government has allocated nearly twice that amount for vaccination”.

In a series of recent tweets, he asked people to “not believe in fake photos and canards about ongoing work at Central Vista Avenue”.

“The transformed Central Vista will be a world class public space,” he said, adding “it will eventually be something every Indian will be proud of”.

A senior bureaucrat who did not want to be named said Mr Puri was trying to “defend the indefensible”.

“I do not doubt that the end result will be something every Indian will be proud of, but I do believe that the timing is completely wrong. What is the tearing hurry to erect yet another building when all around us people are dying?”