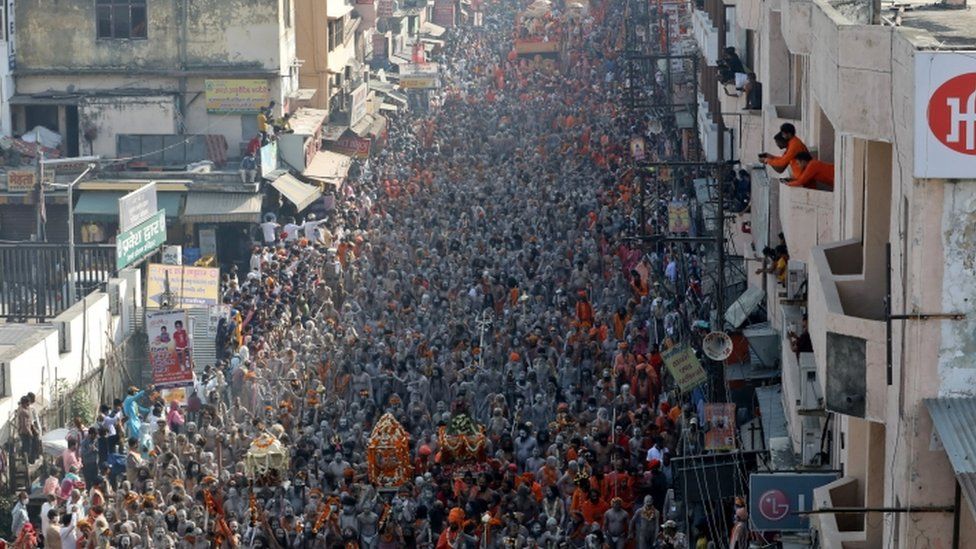

IMAGE COPYRIGHT EPA image caption Hindus believe taking a dip in the Ganges will cleanse them of their sins

By Geeta Pandey

BBC News, Delhi

When millions of devout Hindus gathered last month in the Himalayan town of Haridwar to participate in the Kumbh Mela festival even as India battled a devastating second wave of coronavirus, many feared that it would turn out to be a “super-spreader event”.

Those fears, it now seems, are coming true, with reports of Kumbh returnees testing positive – and possibly spreading the infection – coming from many parts of the country.

When Mahant Shankar Das arrived in Haridwar on 15 March to participate in the festival, cases of Covid-19 were already rising in many parts of India.

On 4 April, just four days after the festival officially began, the 80-year-old Hindu priest tested positive for Covid-19 and was advised to quarantine in a tent.

But instead of isolating, he packed his bags, boarded a train and travelled 1,000km (621 miles) to the city of Varanasi.

There, his son Nagendra Pathak met him at the railway station and they rode a shared taxi to their village 20km (12 miles) away in the adjoining district of Mirzapur.

He insisted that he did not pass on the virus to anyone else, but within days, his son and a few other villagers also developed Covid symptoms.

Mr Pathak, who’s also made a full recovery, says their village has seen “13 deaths in the past fortnight from fever and cough”.

The infections in the villagers may – or may not – be linked to Mahant Das, but health experts say his behaviour was irresponsible and that by travelling in a crowded train and sharing a taxi, he may have spread the virus to many along the way.

Epidemiologist Dr Lalit Kant says “huge groups of mask-less pilgrims sitting on the river bank singing the glories of the Ganges” created an ideal environment for the virus to spread rapidly. “We already know that chorus singing in churches and temples are known to be super-spreader events.”

IMAGE COPYRIGHT REUTERS

IMAGE COPYRIGHT REUTERSIn Haridwar, officials said 2,642 devotees had tested positive, including dozens of top religious leaders.

With growing fears that the Kumbh returnees could start to infect others, several worried state governments ordered a 14-day mandatory quarantine and warned of strict action against those who withheld information about their travels.

Some made the RT-PCR test mandatory for them, but few states have a database of travellers and no state has a foolproof system of testing and tracing those entering its borders.

In the past fortnight, reports of Kumbh returnees testing positive have come from all over India:

- Authorities in Rajasthan blame the pilgrims for the rapid spread of Covid cases in the state, especially in rural areas

- At least 24 Kumbh visitors tested positive on return to the eastern state of Odisha (formerly Orissa)

- In Gujarat, at least 34 of a total of 313 passengers returning by one train were positive

- And 60 of the 61 – or 99% – returnees tested in a town in central Madhya Pradesh state were found to be infected. Officials are now frantically looking for 22 others who are missing

“It’s disastrous,” says Dr Kant. “And these numbers are only the tip of the iceberg. The groups of pilgrims travelling in crowded trains and buses would have the multiplier effect on the number of infections. I can say without hesitation that the Kumbh Mela is one of the main reasons behind the rise in cases in India.”

Mahant Das is combative when I ask him if it would have been better to cancel the Kumbh at a time India was recording huge surges in daily cases and hospitals were turning away patients due to a shortage of beds, medical oxygen and life-saving drugs.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT REUTERS

IMAGE COPYRIGHT REUTERSCritics say Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s reluctance to cancel the gathering was because of possible backlash from Hindu religious leaders like Mahant Das. The priests, the seers and the ascetics are among the party’s biggest supporters and play an important role in mobilising Hindu votes during elections.

On 12 April, the first big day of the festival – when more than three million devotees took a dip in the river Ganges in the belief that bathing there would help them attain salvation – India logged more than 168,000 new cases, overtaking Brazil to become the country with the second-highest number of cases globally.

The festival was scaled down only a week later after the lead monk of one of the participating groups died. Mr Modi requested the seers to turn the festival from then on into a symbolic event.

But the damage had already been done.

Last week, the event organisers said 9.1 million pilgrims visited Haridwar even as the Uttarakhand high court said the state had become a “laughing stock by allowing the Kumbh Mela in the midst of a raging pandemic”.

There had been concerns from the start that holding the Kumbh was fraught with risks.

Health experts had warned the government in early March that “a new and more contagious variant of the coronavirus was taking hold in the country” and letting millions of largely unmasked people gather for a festival was not prudent.

Uttarakhand’s former chief minister, Trivendra Singh Rawat, told me that he had planned the Kumbh to be a “limited, symbolic event” from the start because experts were “telling me that the pandemic is not going to end soon”.

“The festival attracts people from not just India, but other countries too. I was worried that healthy people would visit Haridwar and take the infection back with them everywhere. ”

But just days before the festival, he was replaced by Tirath Singh Rawat, who famously remarked that with “the blessings of Ma Ganga [Ganges, the river goddess] in the flow, there would be no corona”.

The new chief minister said “nobody will be stopped”, a negative Covid report was not necessary to attend, and that it would be enough to follow safety rules. But as millions descended on the town, officials struggled to impose safety norms.

Haridwar’s chief medical officer, Dr Shambhu Kumar Jha, told me that crowd management became “very difficult” because people didn’t come with negative reports and that they “couldn’t turn back the devout who had come all the way driven by faith”.

“You can’t hang people for wanting to attend a religious festival, can you?” he asked.

“There were standard operating procedures (SOPs) by the federal government and the high court and we tried our best to implement them,” he added.

“With crowds of that size, SOPs became almost impossible to follow. They look very good on paper, but it’s impossible to implement them,” Anoop Nautiyal, founder of an Uttarakhand-based think tank, told the BBC.

Mr Nautiyal, who has been collating the health ministry data since the state recorded its first case on 15 March 2020, says Uttarakhand had recorded 557 cases in the week from 14 to 20 March, just as pilgrims had begun arriving. The cases rose rapidly after that, with 38,581 cases recorded between 25 April and 1 May – the last week of the festival.

“It will be wrong to say all the cases were because of the festival, but the surge has coincided with the festival,” he said.

I asked Dr Kant if there’s anything India could do now to contain the damage done by allowing the gathering.

“Someone said that the devotees will take the coronavirus as prasad [god’s blessing] and spread it. It’s tragic that the pilgrims have carried the infection everywhere,” he said.

“I can’t think of anything that can be done now to rectify the situation. Our ship has gone too far out into the sea. We can’t even return to the safety of the harbour. It’s very, very tragic. I just pray that the infections were mild and people can get over them.”