IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGES image caption Only one in three voters turned out for the first round last Sunday and the proportion of young French voters was even smaller

By Lucy Williamson

BBC Paris correspondent

For some of them, France’s regional elections this month are their first ever opportunity to vote. But when polls opened for the first round of voting last Sunday, almost 90% of the country’s youngest voters failed to show up.

Abstention rates were only slightly lower for voters under 35. The second round run-offs take place on Sunday.

‘Politics is a huge lie’

“I absolutely did not vote,” said Jean-Lucien. “Politics is a huge lie.”

I didn’t vote. I’m not really interested, I don’t think it changes anything. I didn’t even remember there was an election

“People are turning to other means of action,” added Alexandre. “Like activism, which can have a more concrete and direct impact on people’s lives.”

It’s not just the youngest voters who seem uninspired by this election. France’s recorded its lowest ever turnout in an election last Sunday, with two out of three voters staying at home.

Covid restrictions blocked a lot of campaigning – but the problem is deeper than that. President Emmanuel Macron called it a “democratic alert”.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT AFP

IMAGE COPYRIGHT AFPEven some older voters, who made it to the polling station, were uninspired by the choices on offer. François Tessé, an engineer in Paris, said it wasn’t easy to choose who to vote for.

“I don’t have a predefined idea,” he told me. “[Politics] has changed over the past few years; it was clearer before.”

Success for mainstream parties

The irony is that the first round of this election has left France looking much like it did five years ago, before President Macron is supposed to have “redrawn the political map”.

Incumbents from France’s traditional centre-right and left-wing parties are the main winners, going into the second-round run-offs.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGESMr Macron’s main far-right opponent, Marine Le Pen, has done worse than expected, while the president’s own party has so far struggled to make much of an impression at all.

“It’s very risky to go to the next presidential election with such a weak political organisation. It’s worked once; it doesn’t prove that it’s going to work a second time.”

Who to look out for in run-off votes

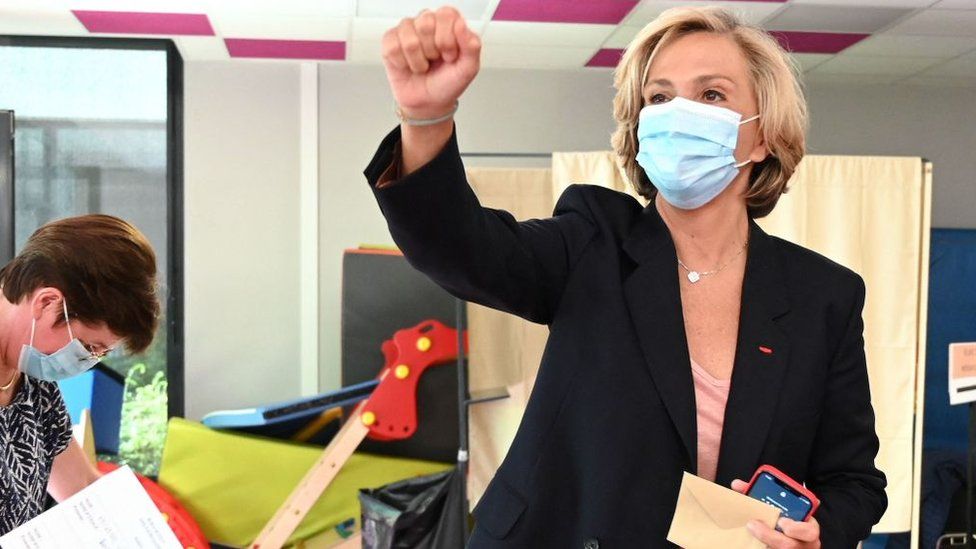

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGES- Xavier Bertrand – 41% of first-round vote in Hauts-de-France – bidding to be Republicans presidential candidate

- Laurent Wauquiez – 43% in Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes – Republicans

- Valérie Pécresse -35% in Paris region of Ile-de-France – Republicans

- Thierry Mariani – 36% in Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur -National Rally, up against Renaud Muselier (31%) of Republicans

- Carole Delga – 39% in first round in Occitanie – Socialists

- Greens/Socialist alliance of Matthieu Orphelin and Guillaume Garot (35% combined) against Christelle Morançais of Republicans (34%) in Pays de la Loire

Ms Le Pen’s National Rally is still in with a chance to win a region in the run-off this Sunday. That would be a major step up for a party that’s never controlled anything bigger than a town hall in France.

Campaigning at a market in Provence last week, Ms Le Pen posed for selfies every few metres. The party is running a new “calm and responsible” image – with a candidate poached from the mainstream centre right – all designed to broaden its support, among voters like Rose.

“It’s less extreme, for sure,” Rose told me. “I have a lot of people around me who are right-wingers like me, and who are going to try the National Rally.”

IMAGE COPYRIGHT REUTERS

IMAGE COPYRIGHT REUTERSBut new converts aren’t always as committed to voting as core supporters. Turnout for the National Rally last Sunday was unusually low.

The party is also facing stiff opposition in Provence this Sunday from the centre-right Republicans – so far, the biggest winners in this election.

“What’s at stake is colossal,” François de Canson, one of the Republicans’ candidates in Provence told me last week.

“We are a rampart, we must stay a rampart,” he said. “If we win this election, it would be a strong symbol that the National Rally can’t conquer France.”

François likes to end town-hall meetings with the Marseillaise.

After all, this regional election, largely ignored by voters, is seen by politicians as the aperitif to France’s presidential race.