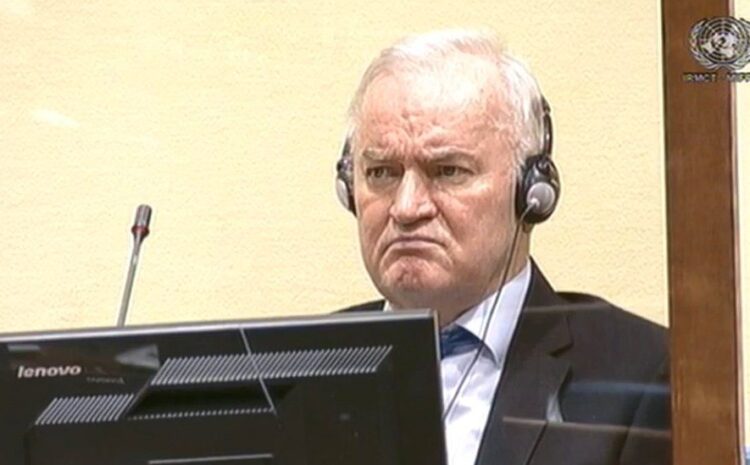

image caption Ratko Mladic was in court to hear the verdict on Tuesday

The UN court upheld the life sentence for his role in the killing of around 8,000 Bosnian Muslim (Bosniak) men and boys in Srebrenica in 1995.

The massacre, in an enclave supposed to be under UN protection, was the worst atrocity in Europe since World War Two.

It is not yet clear where Mladic will serve the rest of his sentence.

The five-person appeals panel found Mladic had failed to provide evidence to invalidate the previous convictions against him, although the presiding judge dissented on almost all counts.

However, the Appeals Chamber also dismissed the appeal brought by the prosecution, which had sought a second conviction against Mladic over crimes committed against Bosnian Muslims and Bosnian Croats in some other areas during the war.

Survivor Semso Osmanovic, who lost 23 family members in the massacre, told the BBC’s Guy De Launey that the verdict meant he finally felt able to return to his home town.

But the former general’s son, Darko Mladic, said his father “did not have a chance for a fair trial” and described the proceedings as “a travelling circus”.

Mladic had denounced the tribunal during his appeal hearing in August, calling it a child of Western powers. His lawyers had argued he was far away from Srebrenica when the massacre happened.

Mladic, known as the “Butcher of Bosnia”, was one of the last suspects to face trial at the UN’s International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. He was arrested in 2011 after 16 years on the run.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT REUTERS

IMAGE COPYRIGHT REUTERSIn 2016, the same court convicted former Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadzic of planning the Srebrenica massacre, among other crimes.

His initial 40-year sentence for genocide and war crimes was later increased to life in prison in 2019 – the remainder of which he will serve in the UK.

Long wait for justice

“He has blood on his hands,” Munira Subasic told me when I visited her home, a short walk away from the killing fields of Srebrenica.

Ratko Mladic was the enforcer of a political plot, engineered at the top, to make sections of Bosnia’s Muslim population disappear.

The ethnic cleansing began with persecution – propaganda turned neighbours against one another – and for many thousands it ended when Ratko Mladic’s men overran the UN base at Potocari, a designated safe zone.

It was here that Munira’s 17-year old son Nermin was torn from her arms, as he tried to reassure her everything would be fine. Twenty-two members of her family perished in the genocide.

Ratko Mladic spent 16 years as a fugitive, many feared he wouldn’t live to see this final legal judgment.

Munira travelled to The Hague to witness the moment she believes will bring her peace.

Prosecutors here hope this trial sends a message that resonates in the region and beyond – that justice delayed does not mean justice denied.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT REUTERS

IMAGE COPYRIGHT REUTERSWhat happened during the appeal?

The hearing in August had been delayed by Mladic’s health problems and coronavirus restrictions.

He remained defiant throughout, attacking both the court and the prosecutor.

Speaking about Srebrenica, he said he had signed an agreement with the Bosnian Muslim army to honour it and other protected areas, and suggested he was not to blame for any violation of these zones.

But prosecution lawyer Laurel Baig said Mladic had been convicted of some of “the most heinous crimes of the 20th Century”.

“Mladic was in charge of the Srebrenica operation,” she said. “He used the forces under his command to execute thousands of men and boys.”

A defence lawyer, Dragan Ivetic, denied his client had played a role, saying: “Mr Mladic is not a villain. He was someone who at all times was trying to help the UN do the job it couldn’t do in Srebrenica at a humanitarian level.”

How did the genocide happen?

Between 1991 and 1999 the socialist state of Yugoslavia broke up violently into separate entities covering the territories of what were then Serbia and Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia and Slovenia.

Of all the conflicts, the war in Bosnia was the bloodiest as, ethnically and religiously, it was the most divided.

Yugoslav army units, withdrawn from Croatia and renamed the Bosnian Serb Army, carved out a huge swathe of Serb-dominated territory in Bosnia.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT AFP

IMAGE COPYRIGHT AFPMore than a million Bosniaks and Croats were driven from their homes in so-called ethnic cleansing, and Serbs suffered too. By the time the war ended in 1995, at least 100,000 people had been killed.

At the end of the war in 1995, Mladic went into hiding and lived in obscurity in Serbia, protected by family and elements of the security forces.

He was finally tracked down and arrested at a cousin’s house in rural northern Serbia in 2011.