That’s the future catastrophe imagined by Susan Donovan, a high school teacher and science fiction writer based in New York. In her self-published story New York Hypogeographies, she describes a future in which vast amounts of data get deleted thanks to electrical disturbances in the year 2250.

In the years afterwards, archaeologists comb through ruined city apartments looking for artefacts from the past – the early 2000s.

“I was thinking about, ‘How would it change people going through an event where all of your digital stuff is just gone?’” she says.

In her story, the catastrophic data loss is not a world-ending event. But it is a hugely disruptive one. And it prompts a change in how people preserve important data. The storms bring a renaissance of printing, Donovan writes. But people are also left wondering how to store things that can’t be printed – augmented reality games, for instance.

Data has never been completely safe from obliteration. Just consider the burning of the Great Library of Alexandria – its very destruction is possibly the only reason you’ve heard about it. Digital data does not disappear in huge conflagrations, but rather with a single click or the silent, insidious degradation of storage media over time.

You might also like:

- The trouble with big data? It’s called the ‘recency bias’

- The tiny bits of code that can wreck computers

- How to destroy your digital history

Today, we’re becoming accustomed to such deletions. There are lots of examples – the MySpace profiles that famously vanished in 2019. Or the many Google services that have shut down over the years. And then there are the online data storage companies that have offered to keep people’s data safe for them. Ironically, they have sometimes ended up earmarking it for deletion.

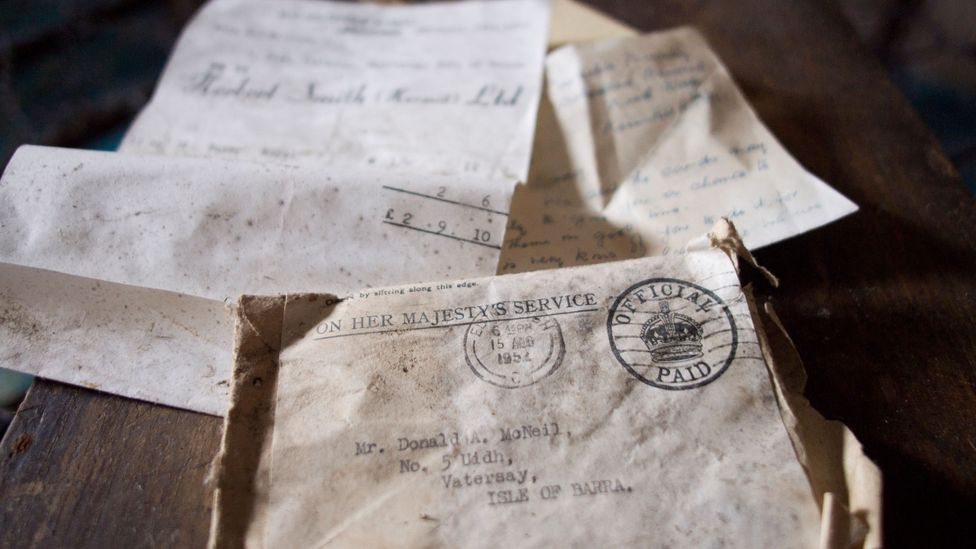

In other cases, these services actually keep running for long periods. But users might lose their login details. Or forget, even, that they had an account in the first place. They’ll probably never find the data stored there again, like they might find a shoebox of old letters in the attic.

Donovan’s interest in the ephemerality of digital data stems from her personal experiences. She studied maths at university and has copies of her handwritten notes. “There’s a point when I started taking digital notes and I can’t find them,” she says with a laugh.

Story continues below

The Great Library of Alexandria was a vast repository of physical knowledge in the ancient world, much of which was accidentally destroyed (Credit: Alamy)

She also had an online diary that she kept in the late 1990s. It’s completely lost now. And she worked on creative projects that no longer survive intact online. When she made them, it felt like she was creating something solid. A film that could be replayed endlessly, for instance. But now her understanding of what digital data is, and how long it might last, has changed.

“It was more like I produced a play, and you got to watch it, and then you just have your memories,” she says.

Thanks to the permanence of stone tablets, ancient books and messages carved into the very walls of buildings by our ancestors, there’s a bias in our culture towards assuming that the written word is by definition enduring. We quote remarks made centuries ago often because someone wrote them down – and kept the copies safe. But in digital form, the written word is little more than a projection of light onto a screen. As soon as the light goes out, it might not come back.

That said, some online data lasts a very long time. There are several examples of websites that are 30 years old or more. And now and again data hangs around even when we don’t want it to. Hence the emergence of the “right to be forgotten”. As tech writer and BBC web product manager Simon Pitt writes in the technology and science publication OneZero, “The reality is that things you want will disappear and things you don’t will be around for forever.”

Someone who aims to redress this balance is Jason Scott. He runs Archive Team, a group dedicated to preserving data, especially from websites that get shut down.

He has presided over dozens of efforts to capture and store information in the nick of time. But often it’s not possible to save everything. When MySpace accidentally deleted an estimated 50 million songs that were once held by the social network, an anonymous academic group gave Archive Team a collection of nearly half a million tracks they had previously backed up.

“What are my children or any potential grandchildren […] going to do with the 400 pictures of my pet that are on my phone?” – Paul Royster

“There were bands for whom MySpace was their only presence,” says Scott. “This entire cultural library got wiped out.”

MySpace apologised for the data loss at the time.

“Once you delete the stuff it just disappears utterly,” says Scott, explaining the significance of proactive efforts to preserve data. He also argues that society has, to an extent, sleepwalked into this situation: “We did not expect the online world was going to be as important as it was.”

It should be clear by now that digital data is, at best, slippery. But how to curb its habit of disappearing?

Scott says he thinks there should be legal or regulatory requirements on companies that give people the option to retrieve their data, for a certain period – say, five years – after an online service is due to shut down. Within that time, anyone who wants their information could download it, or at least pay for a CD copy of it to be sent to them.

Not all of the data we accumulate each day will be worth preserving forever (Credit: Alamy)

A small number of companies have set a good example, he adds. Scott points to Glitch, a 2D online multiplayer game that was removed from the web in 2012, just over a year after it was launched. Its liquidation, in data terms, was “basically perfect”, says Scott. Others, too, have praised the fact that the game’s developers acknowledged players’ frustrations and gave them ample opportunity to download their data from the company’s servers before they were switched off.

Some of the game’s code was even made public and multiple remakes of Glitch, developed by fans, have emerged in the years since.

Should this approach be mandatory, though?

“We should have real-time rights, for example to ask for data deletion, data download, or data portability – to take the data from one source to another,” argues Teemu Ropponen at MyData.

He and his colleagues are working on systems designed to make it easier for people to transfer important data about themselves, such as their family history or CV, between services or institutions.

Ropponen argues that there are efforts within the European Union to enshrine this sort of data portability in law. But there is a long way to go.

Even if the technology and regulations were in place, that doesn’t mean that preserving data would become easy overnight. We have so much of it that it is actually quite hard to fathom.

“We should set aside one day of the year when we all go through our data – data preservation day,” – Paul Royster

Around 150 years ago, making a photograph of a family member was a luxury available only to the wealthiest in society. For decades, this more or less remained the case. Even when the technology became more broadly available, it wasn’t cheap to take lots of snaps at once. Photographs became treasured items as a result. Today, smartphone cameras mean it feels like second nature to take literally hundreds or even thousands of photographs every year.

“What are my children or any potential grandchildren […] going to do with the 400 pictures of my pet that are on my phone?” says Paul Royster at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. “What’s that going to mean to them?”

Royster argues that saving all of our data won’t necessarily be very useful to our descendants. And he disagrees with Scott and Ropponen that laws are the answer. Governments and legislators are often behind the curve on technology issues and sometimes don’t understand the systems they intend to regulate, he says.

Instead, people ought to get into the habit of selecting and preserving the data that is most important to them. “We should set aside one day of the year when we all go through our data – data preservation day,” he says.

Unlike old letters, which are often rediscovered years after being forgotten, online memories are unlikely to last unless you take active steps to preserve them (Credit: Alamy)

Scott also suggests that we should think about what we really want to keep, just in case it gets deleted.

“Nobody is thinking of it as the stuff that we have to preserve at all costs, it’s just more data,” he says. “If it’s written, I would print it out.”

There is another option, though. Miia Kosonen at South-Eastern Finland University of Applied Sciences and her colleagues have been working on solutions for storing digital data in archives and national institutions.

“We converted more than 200,000 old emails from former chief editors of Helsingin Sanomat – the largest newspaper in Finland,” she says, referring to a pilot project by Digitalia, a digital data preservation project. The converted emails were later stored in a digital archive.

The US Library of Congress famously keeps a digital archive of tweets, though it has stopped recording every single public tweet and is now preserving them “on a very selective basis” instead.

Could public institutions do some digital data curation and preservation on our behalf? If so, we could potentially submit information to them such as family history and photographs for storage and subsequent access in the future.

Kosonen says that such projects would naturally require funding, probably from the public. Institutions would also be more inclined to retain information that is considered of significant cultural or historical interest.

At the heart of this discussion lies a simple fact: it’s hard for us to know – here in the present – what we, or our descendants, will actually value in the future.

Archival or regulatory interventions could go some way to addressing the ephemerality of data. But that ephemerality is something we will probably always live with, to some extent. Digital data is just too convenient for everyday purposes and there’s little rationale for trying to store everything.

The question has become, at best, one of personal motivation. Today, we decide either to make or not make the effort to save things. Really save them. Not just on the nearest hard-drive or cloud storage device. But also to backup drives or more permanent media, with instructions for how to maintain the storage over time.

This might sound like an exceptionally dry endeavour, but it need not be. A cultural movement might be all it takes to spur us on.

Many audiophiles insist on buying vinyl in an age of music streaming. Booklovers still make the effort to acquire physical copies of their favourite author’s new work. Perhaps we need an analogue-cool movement for preservationists. People who devote themselves to making physical photo albums again. Who go out of their way to write handwritten notes or letters. These things might just end up being far easier to keep than anything digital, which will likely always require you to trust a system you haven’t built, or a service you don’t own.

As Donovan says, “If something is precious, it’s dangerous, I think, to leave it in someone else’s hands.”

—

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “The Essential List”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.