IMAGE SOURCE REUTERS image caption Afghan security forces have faced a major blow with the loss of Kunduz

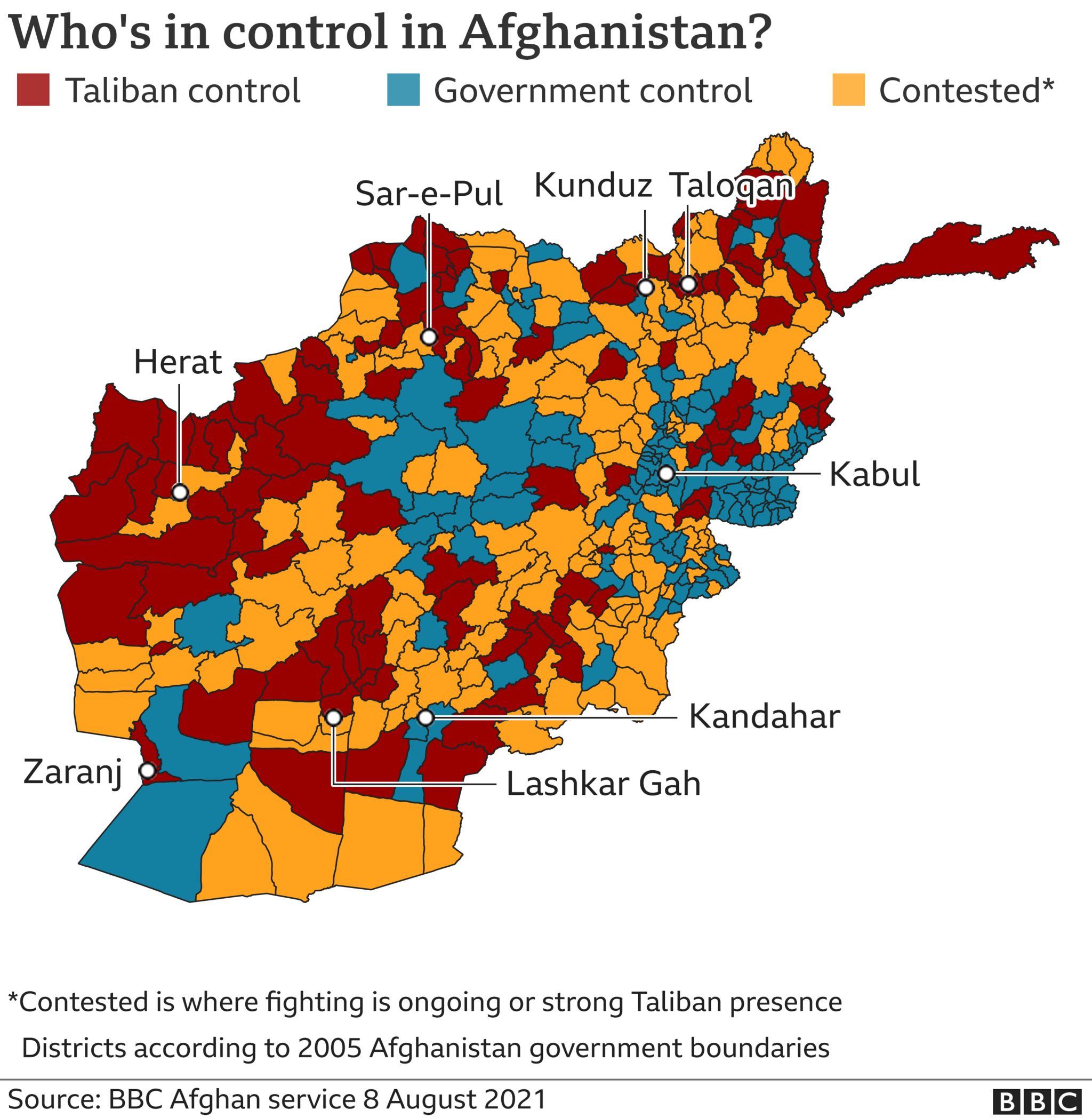

They seized control of the key northern city of Kunduz on Sunday, as well as Sar-e-Pul and Taloqan.

It means five regional capitals have fallen to the militants since Friday, with Kunduz being their most important gain this year.

The Taliban said there is no agreement on a ceasefire with the government.

A spokesman for the group warned against further US intervention in Afghanistan while speaking to Al Jazeera TV on Sunday.

Violence has escalated across Afghanistan after US and other international forces began to withdraw their troops from the country, following 20 years of military operations.

The three northern cities fell to Taliban control within hours of each other on Sunday, with one resident in Kunduz describing the situation as “total chaos”.

The Afghan government, meanwhile, said its forces were fighting to retake key installations.

Heavy fighting has also been reported in Herat in the west, and in the southern cities of Kandahar and Lashkar Gah.

Thousands of civilians have been displaced this year. Families, including babies and young children, have been sheltering in a school in the north-eastern city of Asadabad.

“Many bombs were dropped on our village. The Taliban came and destroyed everything. We were helpless and had to leave our houses. Our children and ourselves are sleeping on the ground in dire conditions”, Gul Naaz told AFP.

IMAGE SOURCE AFP

IMAGE SOURCE AFPThe US has intensified its air strikes on Taliban positions, with Afghan military officials saying militants have been killed. But the Taliban say the air strikes hit two hospitals and a school in the city of Lashkar Gah. Neither claim has been independently verified.

The US embassy in Afghanistan condemned the Taliban’s “violent new offensive against Afghan cities”, saying the group’s actions to “forcibly impose its rule are unacceptable”.

“They demonstrate wanton disregard for the welfare and rights of civilians and will worsen this country’s humanitarian crisis,” it said in a statement.

A big change on the battlefield

By Khalil Noori, BBC News, Kabul

This attack on a number of strategic cities and their fall to the Taliban was unprecedented. But as the deadline for the full withdrawal of foreign forces approached, a big change on the battlefield was expected.

It would be difficult for the Taliban to hold Kunduz, but for several weeks the group has kept control of commercial centres important for trade with Iran and Pakistan.

The populations in cities taken by the Taliban are paying the price of war, having lost loved ones or property. They are having to leave their homes, fearing the launch of a government operation to retake the cities.

Peace talks with the Taliban in Doha are deadlocked. If the process resumes, from now on both sides will be trying to control the larger area to justify a greater share of power, if they agree on a transitional government.

The importance of Kunduz

The seizure of Kunduz is the most significant gain for the Taliban since they launched their offensive in May. The city, home to 270,000 people, is considered a gateway to the country’s mineral-rich northern provinces.

And its location makes it strategically important as there are highways connecting Kunduz to other major cities, including Kabul, and the province shares a border with Tajikistan.

- PROFILE: Who are the Taliban?

- ANALYSIS: How the Taliban retook half of Afghanistan

- FROM THE ARCHIVE: Kunduz, the city the Taliban seized

That border is used for the smuggling of Afghan opium and heroin to Central Asia, which then finds its way to Europe. Controlling Kunduz means controlling one of the most important drug smuggling routes in the region.

It also holds symbolic significance for the Taliban because it was a key northern stronghold before 2001. The militants captured the city in 2015 and again in 2016 but have never been able to hold it for long.

Is Afghanistan being left ‘friendless’?

By Paul Adams, BBC Diplomatic Correspondent

Former British Gen Sir Richard Barrons says there is a danger of Afghanistan feeling “friendless”, in the wake of recent battlefield defeats and the possible withdrawal of diplomats and contractors from Kabul if things get worse.

It is much too early to speculate about a Saigon-style withdrawal from the capital, echoing the way the Americans hastily left Vietnam in the final act of the war there, in 1975.

But in recent days, British and American calls for their nationals to leave the country threaten to create a dangerous narrative.

It is something that western military planners have been worried about for some time, following US President Joe Biden’s decision, in April, to withdraw American forces by 11 September.

In June, classified UK Ministry of Defence documents were found at a Canterbury bus stop by a member of the public. One of them voiced just this concern, speaking about the need to counter an “abandonment narrative” in Afghanistan.

“Precise language may be needed,” it said, “to avoid misunderstandings about ‘retrograde to zero’ vs normal diplomatic (including military) representation.”

“Retrograde to zero” is the peculiar euphemism used to describe the withdrawal process now in its final weeks. In other words, planners were only too aware of creating the dangerous impression that Afghanistan might indeed be left “friendless”.

That is not yet the case. American air strikes are still being used in an attempt to halt the Taliban’s advances. Britain and the US will doubtless have hidden assets on the ground, working feverishly to stem the tide of the war.