IMAGE SOURCE GETTY IMAGES image caption There has been increasing pressure to boycott the Winter Games

By Stephen McDonell

BBC News, Beijing

This had not seemed like it would pose much of a problem. People had become accustomed to life without many Covid restrictions, with authorities stamping out each outbreak of the virus as it came along.

But everything changed when the highly-contagious Delta variant made its way into China via an airport in the eastern city of Nanjing.

In July and August it quickly spread to dozens of cities and towns, threatening China’s status of having the virus controlled.

As they had before, authorities pursued a goal of full elimination.

The strategy is always the same. Phone app health clearance is implemented in order to enter public buildings, track and trace methods go into overdrive and, as infected people are identified, their housing estates placed into lockdown.

At the time of writing, this latest outbreak seems to have been reined in like those before it but officials remain on alert to guard against any new clusters threating the Games with several measures in place.

With these tools, officials are hoping to have zero domestic Covid infections when the Winter Games begin.

This will have a major impact on the look and feel of the Olympics.

IMAGE SOURCE GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE GETTY IMAGESBut this does not necessarily mean no spectators.

Beijing-based Canadian winter sport specialist Justin Downes has been advising Games organisers. He says local officials have been studying how Tokyo managed coronavirus risks for athletes and the decision there to not have crowds.

I asked how this would be achieved. With bubbles?

“That’s the current discussion,” he said. “I mean the organising committee and relevant authorities are not releasing any of these plans until September, so yeah there will definitely be some sort of a bubble involving the athletes and there will be discussion as to who’s vaccinated and who’s not and how those flows work. But, from a winter sports perspective, they tested all of these protocols in Europe last year.”

“There is no question Beijing will be ready in terms of venues for the competitions,” he adds. “In fact, all of the competition venues are already ready and they’ve already hosted test events”.

Across the road from the newly built high-speed train station outside the mountains of Beijing, I speak to Mr Downes as we pass hundreds of workers finishing off the supporting infrastructure around a medal presentation area. There are thousands more electricians, welders and the like at multiple sites nearby.

IMAGE SOURCE GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE GETTY IMAGESThey’re all racing to build food and beverage areas, temporary stands and hotels in time. The spectacular locations will no doubt impress a global audience – from the space-age looking ski jump facility to the beauty of the ski runs.

Protest parks and press freedom

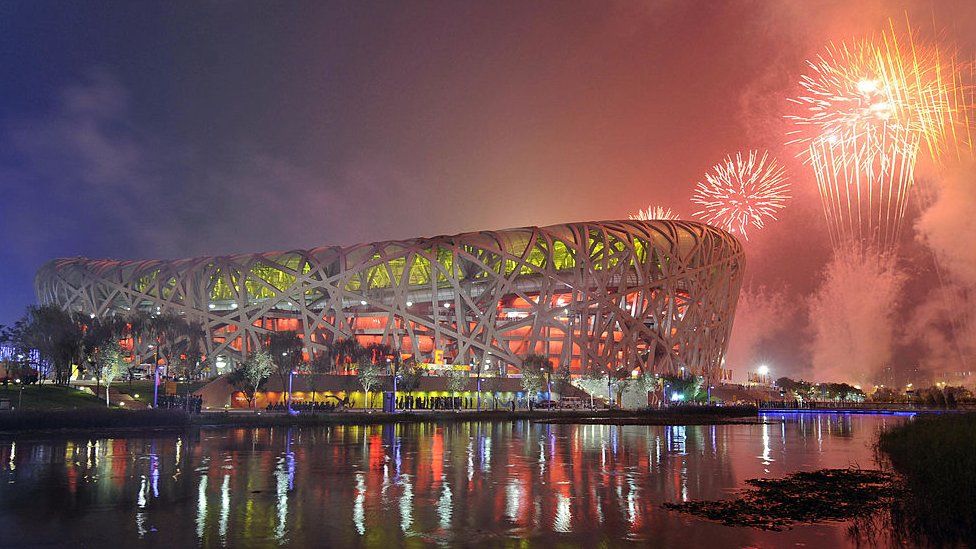

Back in the heart of the capital, facilities built for the Summer Olympics will again be used for Winter events and the Bird’s Nest stadium will once more light up for the opening ceremony.

But recollections of the 2008 Olympics have also dredged up the human rights pressures placed on the Games when held in this country.

In order to secure the Olympics the first time round, Beijing made concessions in terms of opening up and freedom.

It had already lost its bid for the 2000 Games which was awarded to Sydney just four years after the bloody crackdown in and around Tiananmen Square in 1989.

It is an official Olympic requirement for the host city to allow a degree of “press freedom”. With this in mind, in the run up to the 2008 Games, rules for foreign correspondents in China were relaxed, allowing us in theory to travel around the country without first obtaining permission from the local authorities.

Fast forward to 2021: you would struggle to find a foreign correspondent based here who would say they are able to travel around China freely to do their job. Journalists report being harassed, followed and recently threatened with violence.

Interviewees say they have been pressured into not speaking and various arms of the ruling Communist Party have launched attack campaigns on the international press in order to discredit their coverage.

IMAGE SOURCE GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE GETTY IMAGESThere are other significant differences between 2008 and 2021.

Prior to the 2008 Games, to show its newfound openness, Beijing also announced it would allow several so-called “protest parks” to coincide with the event.

The catch was that you needed to apply for and be granted permission in order to use them.

Two grandmothers in their 70s took the government at its word and tried five times to get permission for a protest over a controversial housing development.

Not only were they never allowed to protest but they were given a year’s “re-education through labour” sentence for being troublemakers. After an international outcry, that punishment was later withdrawn.

This time round there will be no protest parks.

Also in 2008, activists overseas followed the Olympic torch around, drawing attention to China’s human rights abuses

When the torch made it to China – some reporters were allowed to travel with it into Tibet. In front of the Potala Palace in Lhasa, its arrival was used for a full-scale nationalist rally.

Standing beside a hand-picked group of traditional dancers, we listened as Tibet’s Communist Party Secretary Zhang Qingli declared that “Tibet’s sky will never change and the red flag with five stars will forever flutter high above it. We are certainly going to smash the splittist schemes of the Dalai Lama clique.”

In China the Olympics becomes political. There is no getting away from it.

During the Beijing Summer Olympics, I also witnessed a group of activists, who had travelled to China for this purpose, manage to unfurl a giant banner at the base of the newly-constructed China Central Television Tower reading “Free Tibet” in huge letters.

A repetition of this type of protest would seem highly unlikely next February. Foreigners visiting for the Games may not be allowed to travel beyond specific Olympic sites and normal tourist visas are unlikely to be granted by then.

In recent years, the most significant human rights flashpoints in China have been the construction of a network of “re-education” camps for ethnic Uyghurs and other minority groups in Xinjiang and the draconian state security law in Hong Kong.

This has all taken place in the years since Beijing was granted the upcoming Winter Olympics. If the camps and the security law had happened before 2015, might they have harmed Beijing’s chances of becoming the world’s first city to host both the Summer and Winter Games?

Many Olympic observers would say that, these days, it might not have made any difference.

IMAGE SOURCE GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE GETTY IMAGESNevertheless there is mounting pressure for a diplomatic boycott in February. Governments are being asked by human rights groups not to send representatives to the Olympics. This call has been supported by votes in the UK and European parliaments.

However, in the end, the Olympic Games is supposed to be about the athletes.

For ordinary Chinese people – despite any criticism this country faces – many say they are excited about hosting the world’s most important sporting festival again and that they are optimistic about what it will bring.

“It’s a huge event. I’m very proud,” one woman visiting the Olympic sites in the mountains told us.

“We had great success here with the Summer Games. The world saw it,” said another who had come for a look.

One way or another, the Games is coming to Beijing again, with the coronavirus, human rights abuses, impressive transport, flash venues and spectacular scenery.

It won’t be a moment in history to miss.