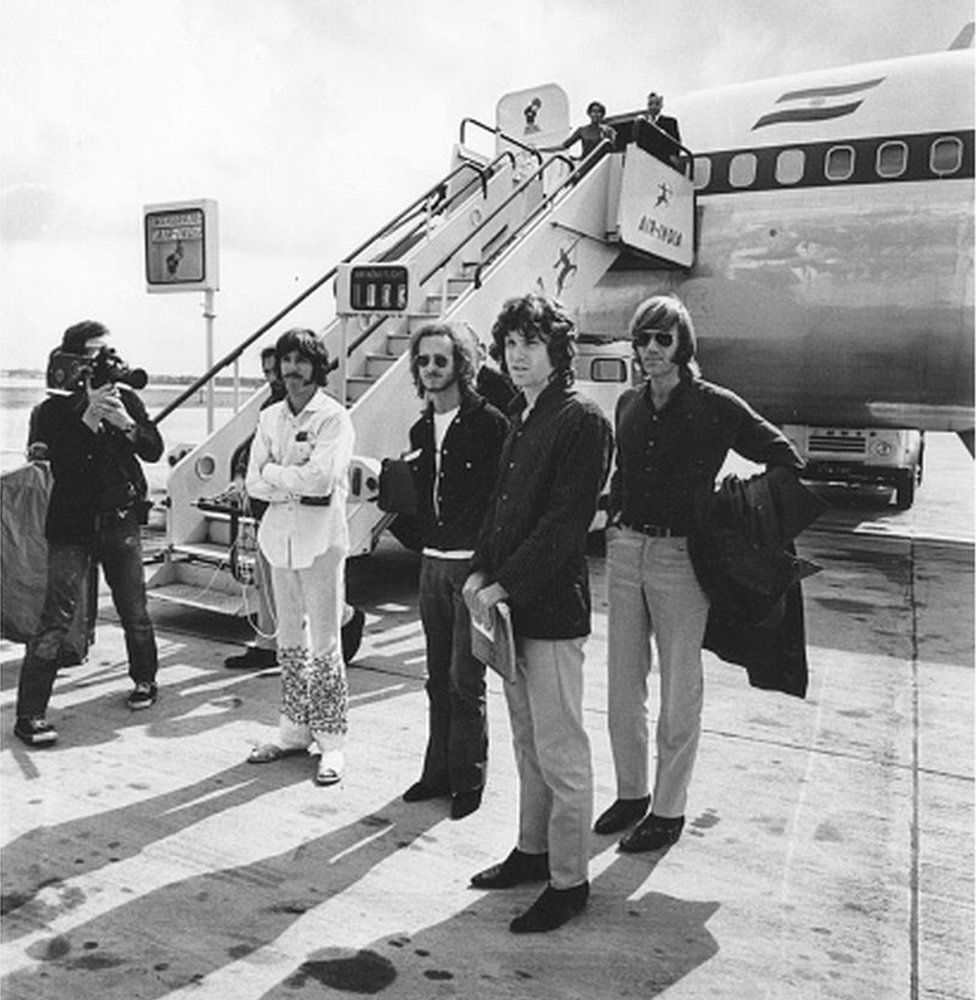

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGES Image caption, Air India has a fleet of more than 140 planes and employs hundreds of pilots and crew

Soutik Biswas

India correspondent

The Puss Moth – one of the two that Tata purchased from England – was beginning a modest weekly mail service.

The plane cruised at 100mph (160km/h), battling headwinds in what was a “bumpy and hot flight”. A bird flew into the cabin and had to be killed.

After a refuelling stop – a bullock cart ferried fuel to the airline in Ahmedabad – the plane landed on a mud flat in Bombay (now Mumbai) in the late afternoon. After offloading some of the mail, the second, waiting plane took off with the remainder of its cargo to two cities in southern India.

The planes had to be started up by swinging the propeller by hand, flew without navigational or landing aids, and had no radio communication.

They routinely took off from the mud-flat near the beach in Bombay where the “sea was below what we called our airfield, and during the high tide of the monsoon, the airfield was at the bottom of the sea,” Tata recounted later.

When the place got flooded, the airline – two planes, three pilots and three mechanics – moved to a small airfield in the city of Poona (now Pune), 150km to the south-east.

IMAGE SOURCE, POTTER AND POTTER AUCTIONS/GADO

IMAGE SOURCE, POTTER AND POTTER AUCTIONS/GADO“Scarcely anywhere in the world was there an air service operating without support from the government. It could only be done by throwing on the operator the financial risk. Tata Sons were prepared to take the risk,” Sir Frederick Tymms, the then chief of civil aviation in the region told a newspaper in 1934.

Over the years, the mail service expanded to other cities. A lone passenger was also accommodated. In 1937, two Tata planes began a service between Delhi and Bombay, each plane carrying 3,500 letters and one passenger. Within six years of starting up, the airline owned 15 planes, an equal number of pilots and three dozen engineers. It claimed a punctuality of 99.4%.

“It took Tata pilots some time to get accustomed to a human riding in the seat behind them,” the tycoon’s biographer, Russi M Lala, noted. “One day a skipper consuming a leg of chicken is reported to have thrown the bone out of the cockpit. It was carried by the wind into the lap of his startled passenger”.

An aviation buff – he had flown his first solo flight as a 25 year old – Tata had always wanted to build a global airline. In the early 1940s, he spoke presciently about the impending “air age” and how air travel would become “as widely available as railway and steamer facilities today”. By 1946, his fledgling airline was carrying one of every three passengers in India and owned nearly half of the roughly 50 planes operating in the country.

IMAGE SOURCE, EXPRESS NEWSPAPERS

IMAGE SOURCE, EXPRESS NEWSPAPERSTwo years later, Air India went international. A brand new Lockheed Constellation plane christened the Malabar Princess took off from Bombay on a flight to London. Tata told the BBC that the flight was the “first by an Asian airline to link the East and West by a regular service”. By the end of that year Air India was making profits.

Tata, a domineering businessman, was punctilious about in-flight service: he once pointed to the colour of tea served on the flight as “indistinguishable” from the colour of coffee; stopped cabin attendants from smoking in the galleys while on duty; and complained that the bacon and tomatoes were often served “stone cold” in the first class breakfast.

He also ticked off his crew for not being properly groomed. “We must know where to draw the line between the odd, the ridiculous and the attractive. Some of your pursers grow sideburns right into their collars! Some have grown drooping moustaches, that make them indistinguishable from Fu Manchu. Some hostesses have buns bigger than their head… please do pay special attention to make-up and appearance” he wrote in a note to one of his managers in 1951.

IMAGE SOURCE, AIR INDIA

IMAGE SOURCE, AIR INDIAIn June 1953, Air India was taken over by the government. India’s aviation industry had flown into heavy weather: profits were falling, too many aeroplanes had been bought, at least two airlines had shut down. The government proposed merging nearly a dozen airlines – only Air India was the standout operator – in a single state-owned corporation. Tata had mixed feelings about it.

For the next three decades Air India continued to shine. The diminutive maharajah, the airline’s world-famous mascot, became one of India’s most recognisable symbols. In bright destination-driven promotional posters he appeared as a Brit with a bowler hat and umbrella; a Frenchman with a beret; and a ruddy, alpine climber from Switzerland.

The planes were named after royalty and Himalayan peaks. By the 1970s Air India had 10,000 employees in 54 countries. “[Even in the 1980s) it was a brand to reckon with. It was one of the few Indian organisations at that time with a global footprint. It had an aura of glamour and excitement,” noted Jitender Bhargava, a former executive director of Air India and author of the book, The Descent of Air India.

IMAGE SOURCE, D CHAKRAVERTY

IMAGE SOURCE, D CHAKRAVERTYThe carrier was making a loss of nearly $2.6m (£1.9m) a day and was racked by debts worth more than $8bn. The airline still had some of the best pilots, but its on-time performance plummeted and service deteriorated.

Now, Air India has returned to the Tata Group, India’s biggest conglomerate. In an emotional note, Ratan Tata, chairman emeritus and cousin of JRD Tata, said the airline under JRD had “gained the reputation of being one of the most prestigious airlines in the world”.

“Tatas will have the opportunity of regaining the image and reputation it enjoyed in earlier years,” he said.

Fasten your seat belts.