IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGES Image caption, This children’s painting adorned the wall of Le Carillon bar after the 2015 attacks

By Hugh Schofield

BBC News, Paris

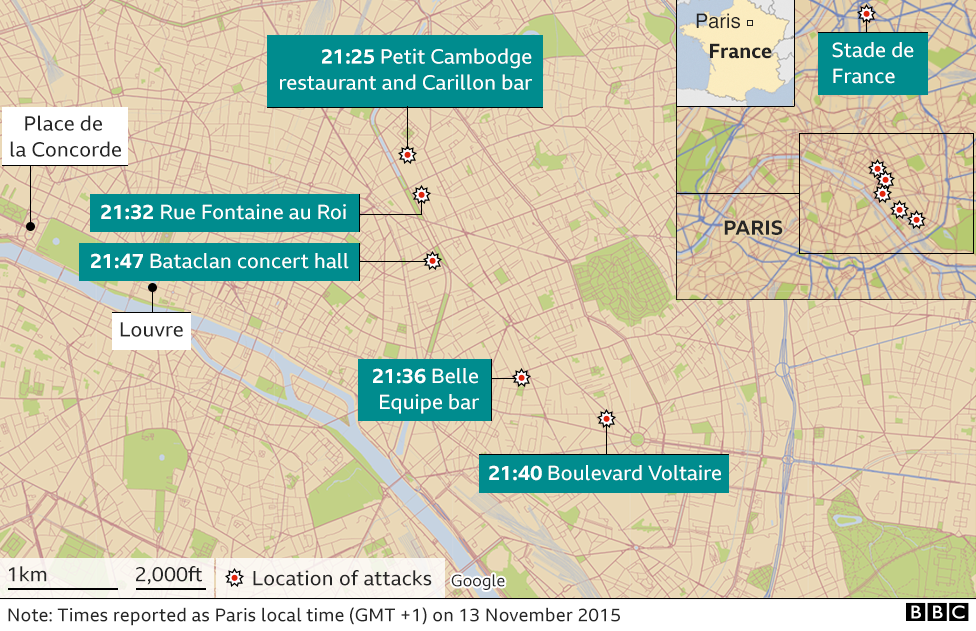

The personal stories of people caught in the November 2015 attacks are now at the heart of the jihadist trial that began in Paris three weeks ago.

For the next five weeks around 350 survivors and relatives of the dead are scheduled to give their accounts. Some have already proved to be unbearably poignant.

On Wednesday, Maya told how she lost her husband Amine and two best friends in the shootings at Le Carillon bar. Like many she asked for her surname not to be released.

Eleven died there, out of the 130 murdered the night of 13 November 2015.

Warning: You may find some of the details in this piece upsetting.

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGESOn the evening of 13 November 2015, Maya was at Le Carillon for a regular Friday evening rendezvous with Amine, his old friend Mehdi, and twin sisters Emilie and Charlotte Meaud.

Maya’s story: All I see is his eyes

[Amine] was my first love. We spoke of the children we would have together. He was beautiful, sunny. He was a great cook. He was funny. He was the man of my life.

I remember exactly what we were talking about. I was 27 at the time and others were 29, so we were talking about their 30th birthdays.

It’s all a big confusion, out of which words and sounds and images come up to the surface.

First I hear the noises, the detonations which I think are fire-crackers, and then there is the smell of gunpowder. I think Amine, Emilie and Charlotte are hiding under the table but in fact they’ve fallen beneath the bullets.

Maya took refuge in the gutter by a car but her legs were sprayed with bullets.

I know straight away that death is around me. Between me and the car is a man. I hear his spasmodic breathing, his rattle, and I know these are his last moments. Something so intimate – I know I am living through the last moments of his life.

IMAGE SOURCE, REUTERS

IMAGE SOURCE, REUTERSI get up, I look for Amine, I see him on the ground lying on his back, his eyes open. I know immediately he is no longer there. I don’t see the wounds, the blood, the bullet holes, the 22 impact points. I don’t see the projectiles that have passed through his body.

All I see is his eyes. Empty. Nothingness. I know he is dead.

Amine, Charlotte, Emilie: none of them ever celebrated their 30th birthday.

Mehdi’s injuries were even worse than mine. It has been too much for him. We have lost touch. Then we were five. Now I am alone here.

Earlier, on Tuesday, the court heard memories of the first episode in the wave of killings: the three suicide bombings outside the Stade de France.

Only one other person was killed in those attacks: Manuel Dias, a 63-year-old coach driver who had brought fans from Reims to the France-Germany football match.

IMAGE SOURCE, HANDOUT

IMAGE SOURCE, HANDOUTHis daughter Sophie recalled that she was in Portugal on the night, preparing for her wedding. In desperation she called dozens of times to Paris before getting confirmation the next day that her father was dead.

“The world fell apart,” she said. “And then there began the long solitary struggle, which every day knocks you down.”

Mounted police officers from the Republican Guard who were patrolling at the Stade de France broke down in tears when they spoke of the events.

“What stays with you is the noise and the smell,” said Pierre. “I was shocked by the sight of a human torso cut in two. And the bits of flesh everywhere.”

Grégory, also on patrol that night, said: “When I went home there were bits of flesh in my hair.”

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGESA journalist named Marylin, who was outside the stadium to get reaction from German supporters, produced before the court the 18-mm screw that penetrated her cheek.

Her cheek still hurt from time to time, she said, “especially around 13 November”.

The three-man gun team began attacking the bars of the 10th and 11th arrondissements shortly after the stadium explosions.

The manager at La Belle Équipe, Grégory Reibenberg, lost Djamila, the mother of his daughter Tess.

“She took some bullets in her back, and that had knocked her out. I woke her. She was alive. She was having difficulty breathing, gasping. But I wasn’t worried.

“I wasn’t thinking about death. I took her hand. Then she said ‘Tess’. And then I knew she was dead. I was still holding her hand. I shut her eyes. I don’t think she suffered.”

Survivors have contrasting feelings towards the 14 men in the dock.

Olivier lost his friend Sebastien at Le Carillon and was himself hit in the left arm. Unlike most others, he gave vent to anger on Wednesday.

“Do you know what Kalashnikov bullets actually do?” he said.

Lifting his arm towards the accused, he continued: “Seven bullets. Boum, boum, boum, boum, boum, boum, boum. That’s what seven bullets do. They destroy a person. It took four days to reconstruct his body, plugging the holes with wax.”

Olivier then read from a prepared text, describing the accused as “junk-grade warriors with brains fried by cannabis”.

The principal accused, Salah Abdeslam, he called “a little yob trying to magnify his pathetic existence by pretending to be a warrior”.

IMAGE SOURCE, ELISABETH DE POURQUERY/FRANCETELE/REUTERS

IMAGE SOURCE, ELISABETH DE POURQUERY/FRANCETELE/REUTERS“If there is any honour left in this country, never open a door to dialogue with the cancer that is Islamism,” he said. “When you are ill you don’t have a conversation with your cancer. You fight it and you kill it.”

In contrast, Claude – who lost a foot and part of his intestine at Le Petit Cambodge – said this to the defendants: “I speak to you without hate… Despite all I have been through I consider you above all to be human beings. If you are ready to start a dialogue and show remorse, I am ready to forgive.

“That means both of us going on a long journey. It won’t bring me back my foot or my intestine. I am prepared to come to talk – even in prison. But first you need to have the courage to be men.”

Rarely do the defendants speak.

Salah Abdeslam, lone survivor from the 10 jihadists who set out on 13 November, has from the start of the trial been the most provocative.

On Thursday he responded to Aminata Diakite, a survivor whose sister Asta was killed next to her in a car outside Le Carillon.

She said that “those who did this are not Muslims. Our Islam forbids us to kill.”

Having got permission to speak, Abdeslam answered her: “What I have to say will not please everyone, but we targeted only non-believers. If we hit Muslims, that was not our intention.”

“I hear a lot of suffering. I hear the victims speak. I don’t doubt they are good people, with many qualities. But there are victims on our side too, in Syria and Iraq, who were hit by coalition strikes.

“We did not target Muslims, and if your sister was Muslim and if she died, that was an accident on our part.”

Only one co-defendant has sought to emerge from Abdeslam’s dominance – Yassine Atar.

On Thursday he said: “I have been extremely distressed by what I have been hearing. Last night I did not sleep – especially after Maya’s account.

“I want people to know there are some of us in the box who are distressed by each story. We are human beings. I speak now to condemn these atrocities with the greatest firmness. I ask victims to let me express my deepest compassion.”

None of the others in the dock has spoken.

The trial continues with more accounts from the café-terrace shootings. After that will come stories from the Bataclan concert hall, given by around 200 survivors and relatives.