IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGES

By Shruti Menon

BBC Reality Check

India also set itself a deadline of 2030 to reduce its emissions by one billion tonnes.

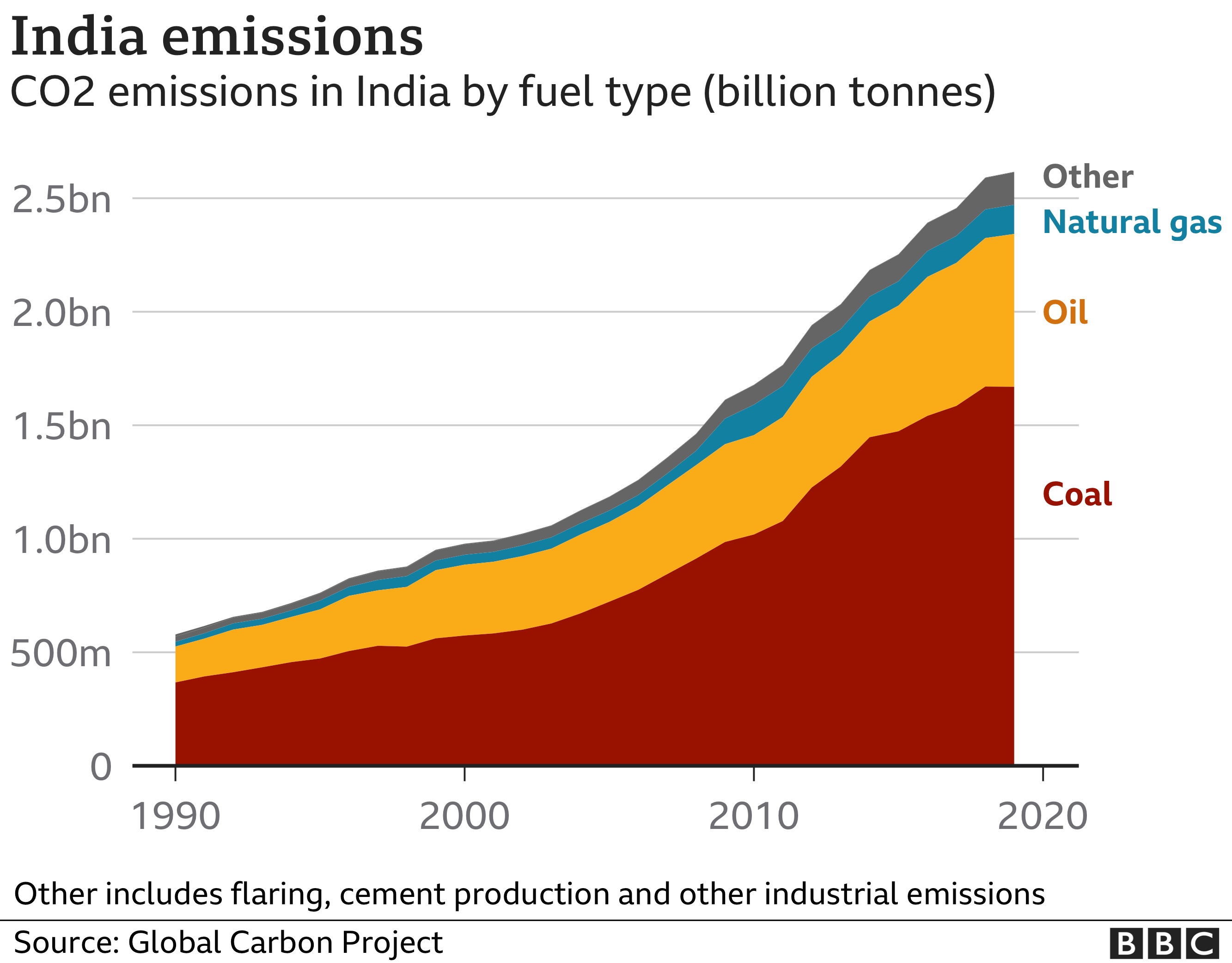

After China and the US, India is the third largest emitter of carbon dioxide (CO2).

With its rapidly growing population and an economy heavily dependent on coal and oil, its emissions are on a steep upward trajectory unless action is taken to curb them.

What emission cuts has India promised?

India has resisted setting overall reduction targets, saying industrialised nations should bear a much greater share of the burden as they have contributed far more towards global warming over time.

It says an “emissions intensity” target, which measures emissions per unit of economic growth, is a fairer way to compare it with other countries, it says.

By 2030 Mr Modi says India will reduce the emissions intensity of its economy by 45% (that’s of all greenhouse gases not just CO2) – a more ambitious target than the previous goal of a 33-35% cut in its emissions intensity from the 2005 level by 2030.

But a fall in carbon emissions intensity does not necessarily mean a reduction in overall emissions.

Climate Action Tracker (CAT), which monitors government policies and actions, says the target is unlikely to have an impact on limiting overall projected emissions.

The Inter-governmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) says a target of global net zero – where a country is not adding to the overall amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere – by 2050 is the minimum needed to keep the temperature rise to 1.5C.

And more than 140 countries have publicly promised to meet this.

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGES

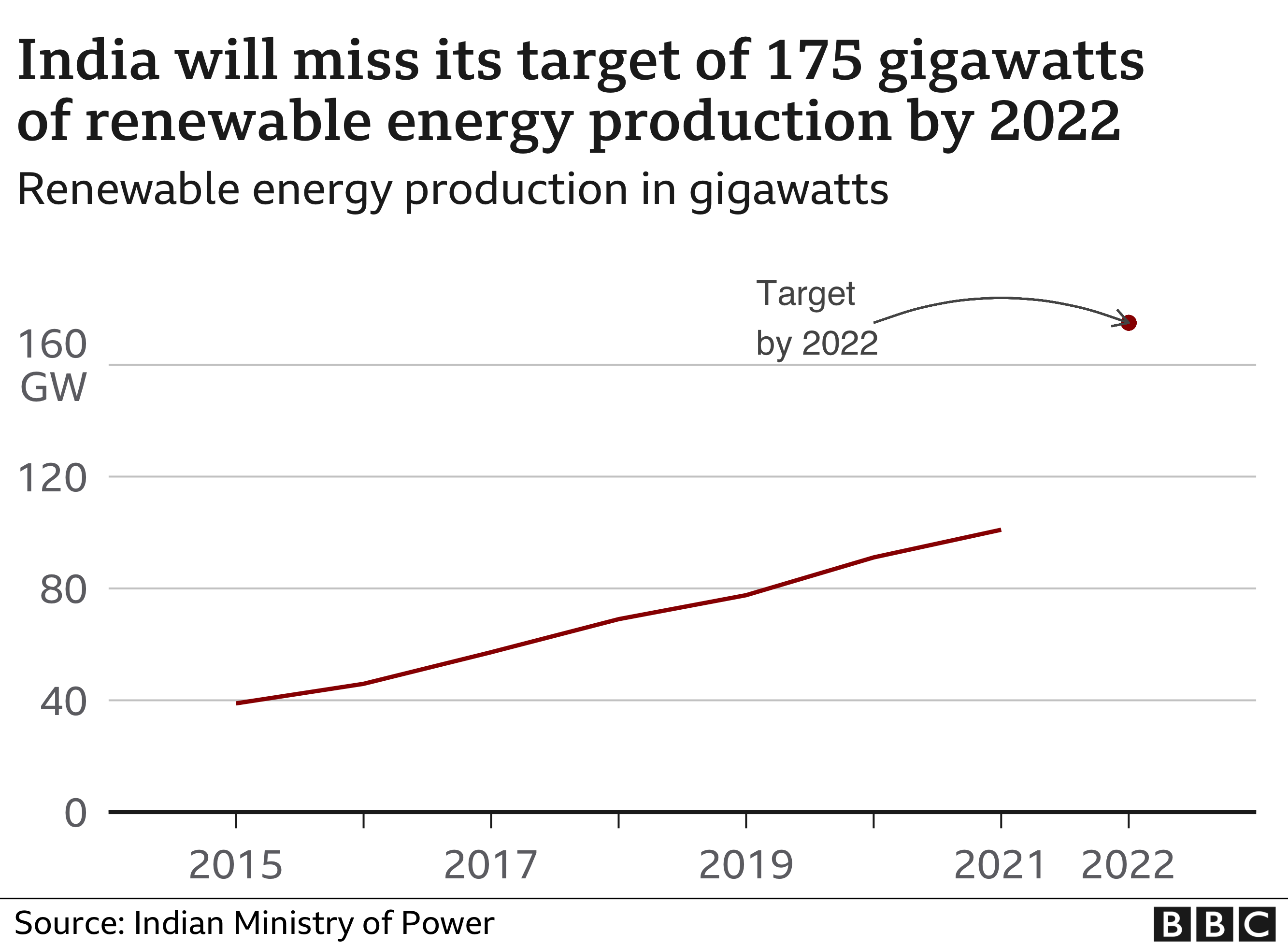

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGESIndia’s prime minister has pledged that it will increase its non-fossil fuel energy capacity to 500 gigawatts (GW) by 2030.

Although the new target for 2030 is more ambitious, it will only have a “small impact on real-world emissions,” says Climate Action Tracker.

Also in 2015, India promised to provide 40% of all electric power from non-fossil fuel sources by 2030. Mr Modi has now increased this figure to 50%.

Generation capacity from these sources stands at around 39% as of September this year, according to India’s official statistics.

But the actual amount generated in 2020 was lower at around 20%, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).

Cindy Baxter, of CAT, says developing countries such as India, need international support to decarbonise their economies and limit the temperature increase to 1.5C in line with the Paris Agreement.

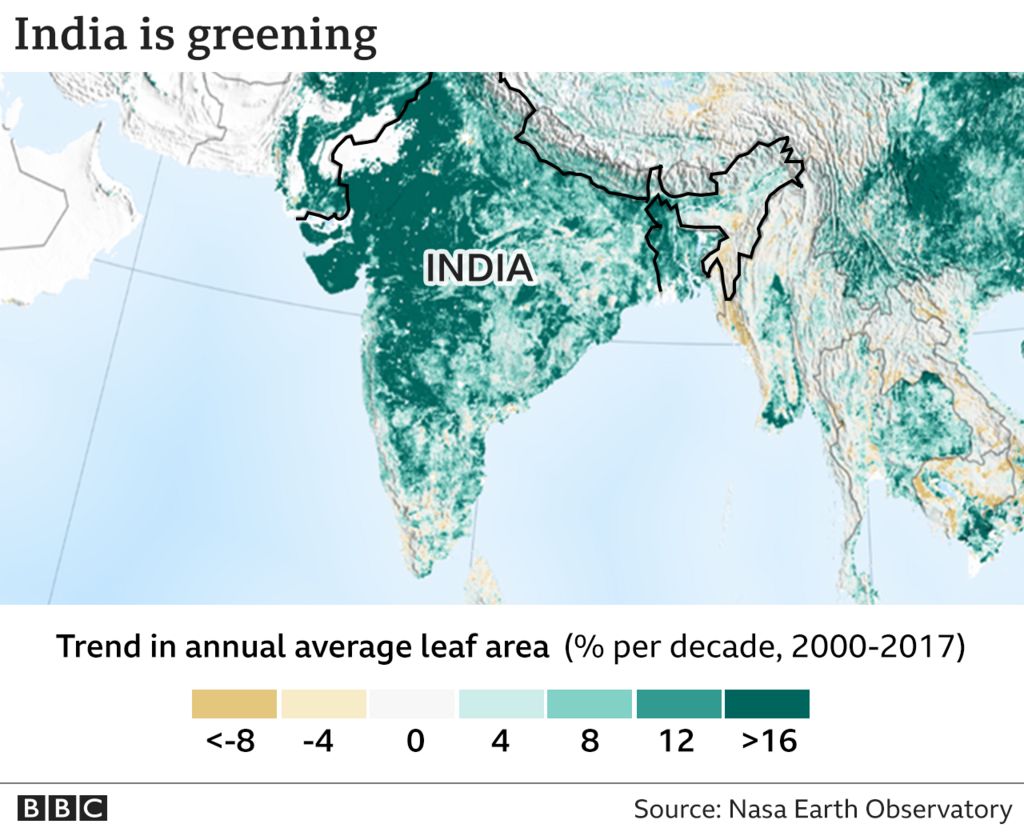

Are India’s forests expanding?

India has highlighted many times it wants to bring a third of its land area under forest cover.

But it has not given a timescale for this – and progress has been patchy.

Although there have been replanting initiatives in the southern parts of India, the north-eastern region has lost forest cover recently.

The expansion of green cover acts a carbon sink.

And India plans to plant enough trees by 2030 to absorb an additional 2.5-3 billion tonnes of CO2 from the atmosphere.

Global Forest Watch – a collaboration between the University of Maryland, Google, the United States Geological Survey and National Aeronautics and Space Administration (Nasa) – estimates India lost 18% of its primary forests and 5% of its tree cover between 2001 and 2020.

But the Indian government’s own survey data indicates a 5.2% increase in forest cover between 2001 and 2019.

This is because the GFW report includes only vegetation taller than 5m (16ft) whereas India’s official calculation is based on tree density over a given area of land.

Additional research by David Brown

The Cop26 global summit, in Glasgow, in November, is seen as crucial if climate change is to be brought under control. Almost 200 countries are being asked for their plans to cut emissions – and it could lead to major changes to everyday lives.