GETTY IMAGES Image caption, The African grey parrot is endangered and it is illegal to sell them

By Shiroma Silva & Carl Miller

BBC Click

Row after row of thin barred cages holds brilliantly coloured birds whose screeches fill the air with a deafening noise.

Faiz Ahmed sits at a desk, oblivious, as he turns to a team of undercover BBC News journalists.

He’s busy with his business of importing and selling birds.

It’s a popular line of trade in Bangladesh, where he’s based, particularly among people with connections and money to invest.

The conversation had started over the purchase of legal captive-bred parrots but turned to a particular species, the African grey.

“Wild grey parrots are good. Many people are breeding from wild ones,” he says.

“It’s hard to get import permission for grey parrots. There’s another species almost the same as the grey parrots, Timneh parrots. It’s possible to get permission for Timneh parrots and import grey parrots instead,” he said.

But how we’ve arrived at Faiz’s establishment is a sign of how drastically the illicit trade in endangered plants and animals has transformed.

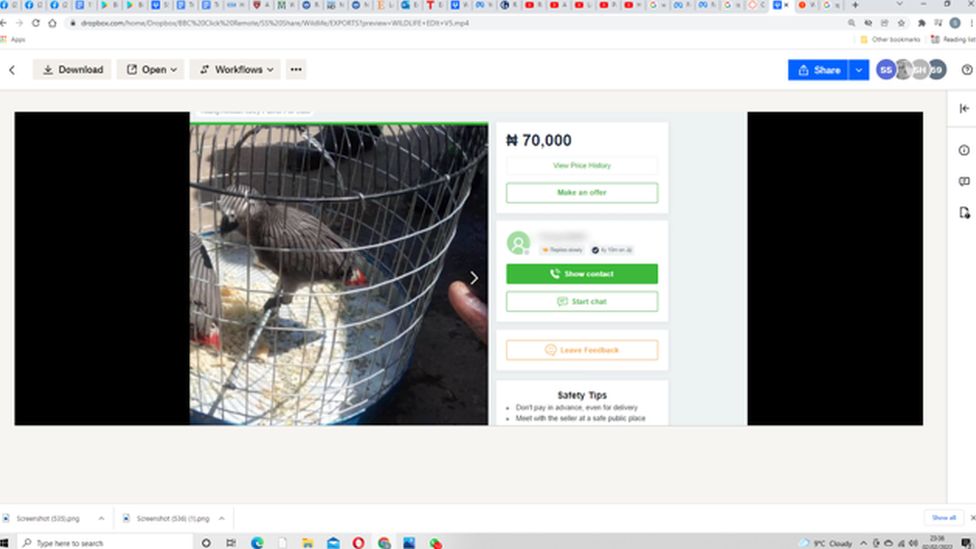

He has been openly advertising the sale of endangered birds and animals across social media.

“The internet has made the setting up of trade routes much easier, and buyers and sellers can communicate with each other much more easily than before,” says Simone Haysom, from Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime (Gitoc).

When Faiz was approached by the BBC’s producer in the UK he first denied having offered to trade wild-caught African greys. He then claimed he didn’t know their import and trade was now illegal, pointing out that there are many such sellers in Bangladesh.

Meanwhile, Rowan Martin, of the World Parrot Trust, says: “More and more people want exotic birds and animals as pets – driven by a desire to own something unusual.

“It was an African grey parrot after all that taught Dr. Dolittle how to speak all the languages of the other animals, so it goes back a long way.

“This is driving wildlife trafficking, not least because wild-caught animals are often cheaper than those bred in captivity.”

Plain sight

Other cyber-crimes, like drug sales and images of child sexual abuse, have typically been pushed into encrypted spaces such as the darknet, but much of the online illicit wildlife trade remains in plain sight.

But there is also a large collection of smaller websites, from classified advert sites in Africa and Asia to specific forums for collectors and enthusiasts, where ownership of these animals is normalised and applauded.

Yet while it is well known there is an illegal activity, wildlife campaigners have had to rely largely on anecdotal evidence to gauge its nature and extent.

The often-elusive nature of the material on the internet has made evidence gathering very ad hoc.

And the tactics of sellers, wise to the online platforms trying to detect their activity, can make the job doubly difficult.

A new project led by Gitoc, bringing together conservationist and technology partners, uses machine learning to identify the language traffickers use.

“Jitot”, for example, means a fully tamed bird, while “raw” signifies wild and plentiful.

So far, the project has found more than 4,500 classified adverts for African greys, among 10,000 likely cases of endangered plants and animals being offered for sale.

And this is likely to be the tip of the iceberg, as the project works to expand its search to illicit commodities, such as bear bile and ivory.

New trends

Facebook and Instagram took down several pieces of content when alerted by BBC News.

Parent company Meta said: “We prohibit the trading of endangered wildlife or their parts.

“Meta is a dedicated member of the Coalition to End Wildlife Trafficking Online. And through our partnerships with the likes of WWF {the World Wide Fund for Nature] and [wildlife trade specialists] Traffic, we are committing to tackling this industry-wide issue.”

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGESOnline harms such as disinformation, hate, and extremism are coming under increased scrutiny. But some conservationists feel an environmental crime has not received the attention it deserves, and that platforms have come under less pressure to respond to it.

“They have the technological capacity to deal with this overnight if there is a will,” says wildlife expert Chris Packham.

“If I had my finger on the conservation purse, I’d spend a lot more money tackling these tech-led issues – because we’re underestimating how much damage is being done and we’ve got to change that.

“We have to elevate the position of wildlife crime because it impacts on all of our lives.”

‘Catastrophic declines’

And while Faiz’s warehouse remains full of birdsong, the forests where these populations live have fallen silent.

Gary Ward, a curator of birds at London Zoo, said this is “because the birds have been trapped out of these environments”.

He added: “We’ve had catastrophic declines of whole suites of bird communities. This isn’t just a climate crisis, it’s also a biodiversity crisis.”