IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGES

By Soe Win, Ko Ko Aung and Nassos Stylianou

BBC Burmese and BBC Data Journalism

Myanmar is seeing increasingly deadly battles between its military and organised groups of armed civilians, new data suggests. Many of those fighting the military are young people who have put their lives on hold since the junta seized power a year ago.

The intensity and extent of the violence – and the coordination of the opposition attacks – point to a change in the conflict from an uprising to a civil war.

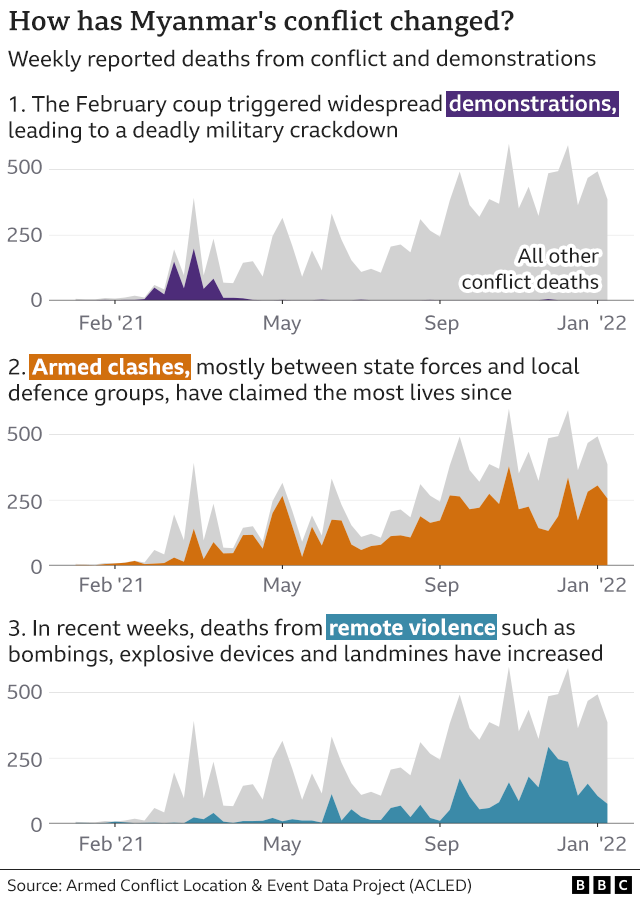

Violence is now spread across the country, according to data from conflict monitoring group Acled [Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project]. Reports from the ground also suggest the fighting has become increasingly co-ordinated and has reached urban centres which have not previously seen armed resistance to the military.

Although precise death tolls are hard to verify, Acled – which bases its data on local media and other reports – has collated figures to suggest about 12,000 people have been killed in political violence since the military seized power on 1 February 2021. Clashes have grown deadlier month on month since August.

In the coup’s immediate aftermath, most civilians died as security forces cracked down on nationwide demonstrations. Now, however, the rising death toll is a result of combat – as civilians have taken up arms – Acled figures show.

UN Human Rights chief Michelle Bachelet agreed in an interview with the BBC that the conflict in Myanmar, also known as Burma, should now be termed a civil war and called on the UN Security Council to take “stronger action” to put pressure on the military to restore democracy. She said the international response to the crisis had “lacked urgency” and described the situation as “catastrophic”, warning that the conflict now threatened regional stability.

The groups fighting government forces are known collectively as the People’s Defence Force (PDF) – a loose network of civilian militia groups largely made up of young adults.

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGESHera [not her real name], 18, had just finished high school when she joined anti-government protests following the coup. She has put university plans on hold to become a PDF platoon commander in central Myanmar. She says she was motivated to join the PDF after the high-profile death of student Mya Thwe Thwe Khaing who was shot during the February 2021 protests. Hera’s parents were initially concerned when their daughter began a PDF combat training course, but they relented when they realised she was serious.

“They told me: ‘If you really want to do it, do it to the end. Don’t give up halfway.’ So I talked to my trainer and fully joined the revolution five days after the training.”

Before the coup, people like Hera had grown up enjoying a degree of democracy. They deeply resent the military takeover and are being supported and trained by other ethnically-driven militias in the border regions who have been fighting the military on and off for decades.

Civil war in Myanmar – how the data was collected

The BBC used figures from Acled, the non-profit organisation, which collects data on political violence and protests around the world. It draws on news reports, publications by civil society and human rights organisations, and security updates from local and international organisations.

While Acled does not independently verify each news report, it says its data on fatalities are continually updated as new information about events and fatality estimates become available. This is due to the difficulty in capturing all relevant events in a conflict zone where reports can often be biased or incomplete, as well as Acled’s policy of recording the lowest estimates reported.

However, it is impossible to get a fully accurate picture of events given both sides are engaging in a fierce propaganda war. Journalists’ reporting is also heavily restricted.

The BBC’s Burmese Service also collected information on fatalities from clashes between Myanmar’s military and the PDF from May to June 2021. This was consistent with trends in Acled’s data.

The PDF is made up of people from all walks of life – farmers, housewives, doctors and engineers. They are united by a determination to overthrow military rule.

There are units across the country, but it is significant that young people from the Bamar ethnic majority in the central plains and cities are taking the lead – joining forces with youths of other ethnicities. This is the first time in Myanmar’s recent history that the armed forces have faced violent opposition from young Bamars.

“Many [civilians] have gone into these militias or created these so-called peoples’ defence forces,” Ms Bachelet told the BBC. “So that’s why for a long time, I’ve been saying that, if we’re not able to do something more strongly about it, it will echo so much the Syria situation.”

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGESNagar, a former businessman who controls several PDF units in the Sagaing Region in central Myanmar, told the BBC that it is not an equal fight. The PDF began with only catapults, although they have since made their own muskets and bombs. The heavily armed military has aerial firepower – used frequently in recent months. It can procure weapons from countries openly supportive of the junta – including Russia and China.

An open source investigation by Myanmar Witness – shared with the BBC – confirmed that Russian armoured vehicles were unloaded in Yangon a few weeks ago.

But the PDF’s strength is its support on the ground in local communities. What began as grassroots resistance has become more organised, daring and battle-hardened. The exiled National Unity Government [NUG] has helped set up and lead some PDF units – and keeps in touch with others more informally.

The PDF have homed in on soft government force targets, such as police stations and poorly-staffed outposts. They have seized weapons, and have bombed junta-owned businesses including telecom towers and banks.

Nagar says the PDF have no choice but to take on the future of the country themselves. “I think resolving the problems at a round table no longer works today. The world is ignoring our country. So I will arm myself.”

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGESHera, who joined the PDF with her older sisters, says their aim is to “root out the military dictatorship”.

“The military has killed innocent people. They destroyed people’s livelihoods, properties and possessions. And they terrorise people. I can’t accept that in any way.”

There have been several incidents of mass killings of civilians by the military, including the deaths of at least 40 men in July – and the killing of more than 35 men, women and children in December.

The BBC has spoken to a man who survived another attack by the military – also in December – by playing dead. Six men – unable to run away when soldiers entered their village in Nagatwin in central Myanmar – were killed. Three of them were elderly and two had mental health conditions, villagers say. The man who survived says junta troops were looking for resistance fighters.

The widow of one the dead men says her husband’s body showed signs of torture. “They killed an old man who couldn’t even speak well enough to explain. I will never forget it. I cry whenever I think about it,” she told the BBC.

The military rarely gives interviews, but in an exclusive interview with the BBC in late 2021 junta spokesman, Zaw Min Tun, described the PDF as terrorists – using the label as justification for action against them.

“If they attack us, we have ordered [our troops] to respond. We are trying to secure the country and the regions by using appropriate force in order to achieve a reasonable level of security,” he said.

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGESIt is difficult to estimate the exact number of fighters on either side. Officially, Myanmar’s military numbers about 370,000 troops – but in reality it could be much smaller. There have been fewer recruits in recent years – and also defections since the coup. Similarly, it is difficult to get an accurate assessment of the number of people in the PDF.

In addition to the units formed by the NUG, some PDF members are being trained, sheltered and even armed by ethnic armed groups operating along the border. Some of the groups had signed ceasefires with previous governments – those ceasefires have now broken.

The PDF has now publicly apologised to ethnic militias for previously believing military propaganda that the groups had wanted to dismantle the country. The PDF is now unanimously calling for a future federal state in which everyone will have equal rights.

A nun – who knelt in front of a police frontline in March 2021 to protect protesters in the wake of the military coup – has told the BBC that the political upheaval since the takeover has had a seismic effect on the lives of the public.

IMAGE SOURCE, MYITKYINAR NEWS JOURNAL VIA REUTERS

IMAGE SOURCE, MYITKYINAR NEWS JOURNAL VIA REUTERS“Children can’t go to school. Education, health, social and economic and livelihood – everything has gone backward,” says Sister Ann Rose Nu Tawng.

“Some aborted children because they couldn’t provide for them due to the poor economy. Parents can’t guide their children properly because of livelihood difficulties.”

But the nun says she admires the young people who have joined the fight.

“They are brave. They don’t mind [sacrificing] their own lives in working to achieve democracy, for the good of the country, to get peace and to get this country liberated [from military rule]. I praise them, I’m proud of them and I respect them.”

Additional reporting by Rebecca Henschke and Becky Dale. Design by Jana Tauschinski.