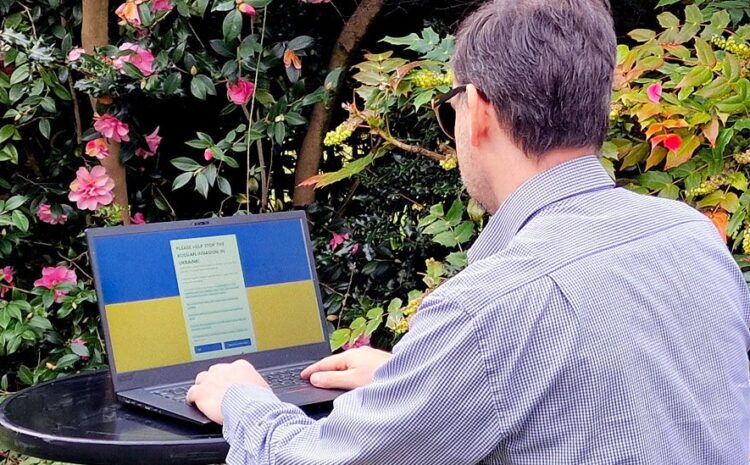

IMAGE SOURCE, FABIAN Image caption, Fabian at work on his spamming website

By Joe Tidy

Cyber reporter

All over Russia email inboxes are pinging.

Millions of messages are being received with the same intriguing subject Ya vam ne vrag – I am not your enemy.

The message appears in Russian with an English translation and it begins: “Dear friend, I am writing to you to express my concern for the secure future of our children on this planet. Most of the world has condemned Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.”

The lengthy email goes on to implore Russian people to reject the war in Ukraine and seek the truth about the invasion from non-state news services.

In just a few days, more than 22 million of these emails landed in Russian inboxes, and they’re being sent by volunteers around the world, who are donating their time and email addresses to the cause.

Elsewhere hacker groups claim to have defaced Russian news websites with messages to Russian people to “stop Putin”.

But the spam email campaign created by a small team in Norway seems to have caught the imagination of thousands of people searching for ways to help Russians learn about the war.

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGES“During the Second World War, and in earlier wars, people flew over Germany with leaflets and dropped them out. This is just a more modern way of trying to get people to open their eyes,” says Fabian, who came up with the idea.

The 50-year-old Norwegian, who runs a computer network business, doesn’t want his surname to be published for fear of retaliation from the Russian authorities. He says he felt compelled to do something after becoming increasingly anxious about the possibility of World War Three.

People power

His website, which the BBC is not naming, is circumventing Russian censorship through a mix of clever computing and people power. The system allows people to send his templated message to dozens of Russian email addresses at once, and he estimates that tens of thousands of volunteers have done this since the website went live.

Users can choose to contact from one to 150 Russian people. Then, with a click, the volunteer’s default email client (Outlook or Gmail, for example) is loaded up with the unique email addresses, subject and body text ready to send.

People are also able to personalise the contents too, to increase the chances of getting their email read.

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGESThere are two reasons, says Fabian, for using people’s personal email accounts: the emails get through email spam filters if they are sent from real accounts, and in small numbers.

“But also, people can actually receive replies from Russians and engage with them and have conversations about the war.”

Fabian says some accounts will be less active than others and in some cases the email may end up in the junk mail folder. But many of the messages are being read, he says, and some Russians are replying.

Replying Russians

Alex, also in Norway, was asked to test the system by Fabian’s team, but has kept sending emails since.

“I’ve sent around 500 emails so far and got around 20 replies within a day, so I’m hoping for more,” he says. “Most of the replies are people asking me to take them off my mailing list but I got talking to a 35-year-old woman from St Petersburg. She told me she wasn’t sure what was going on in the conflict and wanted to know more. She said there was a lack of news coming out of Europe and she wanted to read about it all but didn’t know how to get through the blocks on websites.”

Alex then explained how she could sidestep Russia’s internet blocks

“I think I’ve got a friend in her now!” he says.

Another 18-year-old volunteer shared the reply she received from an unknown Russian. The message argued strongly that she was wrong and it was Ukraine that was killing innocent people which is why “this special operation is a necessary measure”.

Fabian says his team are constantly tweaking the text and subject of their email template to evade email spam filters, and hope many of the 90 million email addresses will eventually receive the message. If they run out of emails to try he says the team will find more.

They have also had to fend off attacks from unknown hackers trying to bring the site down.

‘Not propaganda’

Fabian argues that what he is doing is “not propaganda”. Asked how he feels about spamming millions of people, he replies that the intrusion is justified because the stakes are so high.

Is he putting unsuspecting recipients in danger?

“You can’t charge the recipient of the email. They’re served our email without being able to consent to it, so it’s kind of involuntarily receiving a leaflet. It’s literally a war. You have to stand up for what you believe in. And I believe in this.”