By Paul Kirby

In Paris

Emmanuel Macron has done something no other French president has achieved before: winning re-election while still being in charge of his own government.

The centrist president’s victory over Marine Le Pen may have been convincing, but he has a problem. There are new elections around the corner to France’s National Assembly and a big section of the electorate dislikes him.

“There is a lot of hate,” sociologist Michel Wieviorka told the BBC. “He said last night ‘I am happy’ but I don’t think he can be totally happy because there are plenty of clouds in his sky.”

Politically, if he fares badly in the June elections, he could end up losing his majority and may not be able to form his own government. That’s why his opponents are calling the next vote a “third round”.

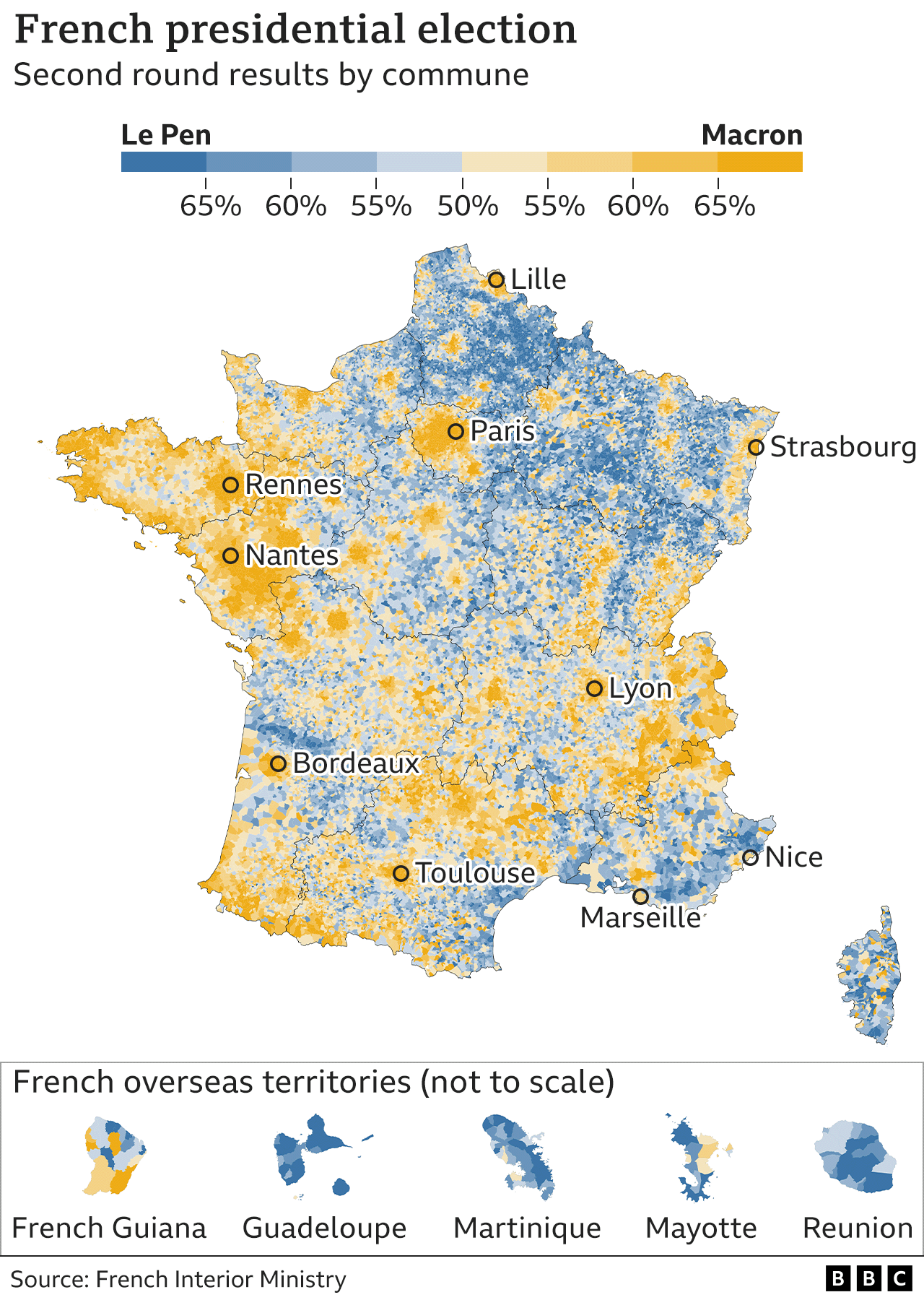

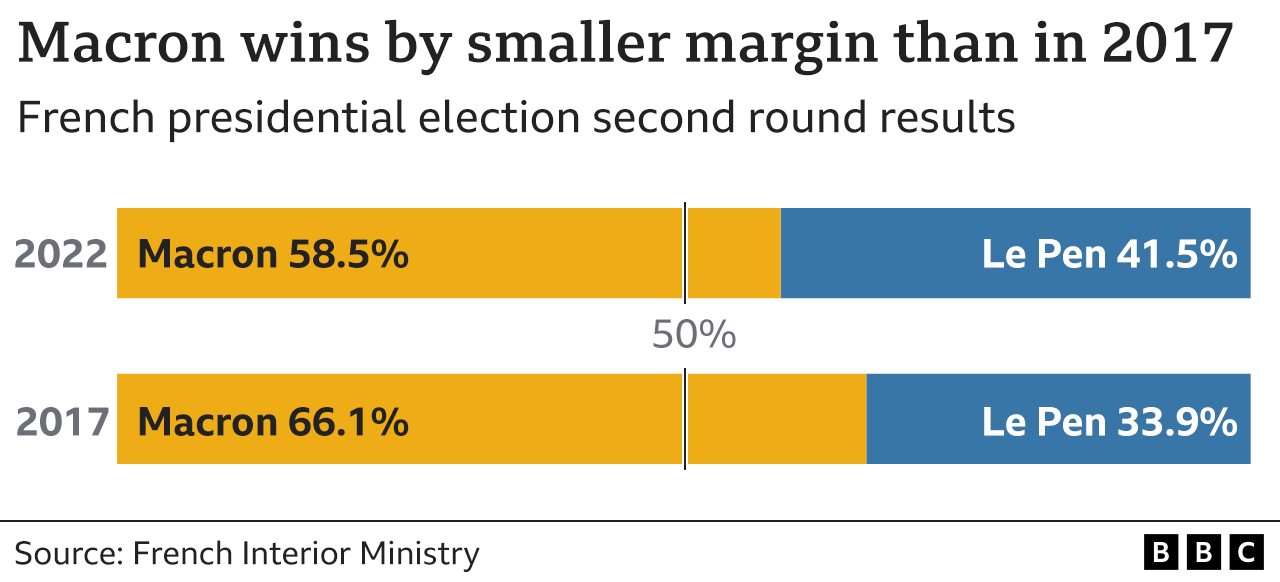

Why would that matter if he’s just won 58.5% of the national vote?

Many of his voters are not natural supporters and are unlikely to back him in June. A large number of far-left voters held their noses to keep the far right out of power, but then there are also a number of mainstream parties that threw their weight behind him too, including the Republicans, Greens and Socialists.

Far-left leader Jean-Luc Mélenchon has designs on becoming prime minister himself. If that were to happen, there would be little love lost between him and the president. He claimed that Mr Macron had won the vote with the worst result in French history. Even if he was wrong, it was still a valid point that more than a third of voters had either stayed away from the election or voted for no candidate at all.

France’s election winner is therefore a man in a hurry. He wants to rush through important reforms to persuade a jaded electorate to vote for his party.

Within days, he needs to form a new government, replacing Prime Minister Jean Castex, who led France through the Covid pandemic.

Labour Minister Elisabeth Borne is seen as a popular choice, because she has a strong record on social issues and it is social reforms that are his priority right now.

Mr Macron is also believed to want a woman in the job.

“We need to provide quick answers,” she said.

Indeed, within hours of the election result, Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire promised to keep in place a price cap on gas and electricity price rises until the end of 2022.

But spending is just one of four priorities Macron needs to push in the coming weeks, according to Junior Economy Minister Agnès Pannier-Runacher. The environment, education, and health are also key, with green issues a particular priority for younger voters.

And don’t forget, 41% of 18 to 24-year-olds did not bother to vote on Sunday.

But the flagship reform Macron is really determined to push through is controversial: raising the pension age from 62 to 65.

He insisted there would be a change of approach over the next five years, and on pensions they would redouble consultation to “hear people’s anxieties”.

Asking the French people to work three more years before they collect their pensions is not exactly a popular move, so Mr Macron is at pains to say he is flexible on how it is brought in and when. And yet his finance minister did not rule out forcing it through without a vote if they had to.

For a president sometimes dubbed Jupiter for perceived arrogance, observers see this as a critical moment for him to adapt.

“He must accept the idea that negotiation is important, it doesn’t mean top-down decisions,” says Michel Wieviorka. “I think it’s difficult for him psychologically and culturally to change to a more democratic way of politics.”

In his victory speech, Mr Macron declared he was no longer a candidate in one camp but the president for everybody. No-one would be left by the wayside, he vowed.

He also insisted that the next five years would be handled differently from the last, without explaining how. He may not have long to prove it.