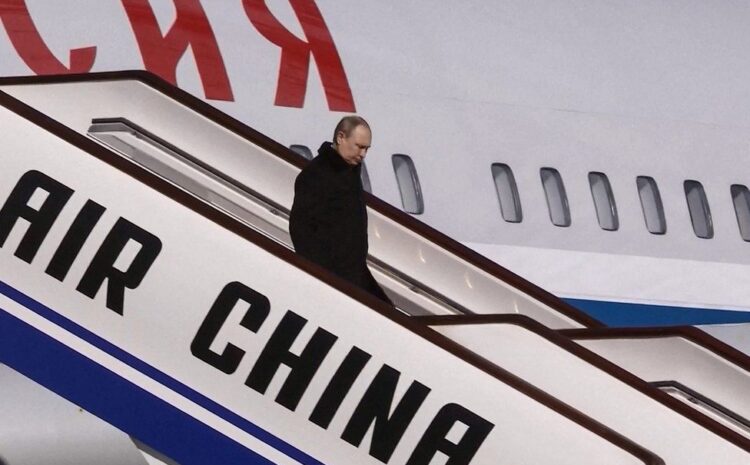

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGES Image caption, President Vladimir Putin arriving in Beijing ahead of his meeting with China’s president and the opening ceremony of the 2022 Winter Olympic Games

By Frank Gardner

Security correspondent

That is what Yevgeny Popov, a member of the Russian Duma (parliament) and an influential TV host in Russia, told the BBC’s Ukrainecast on 19 April. “Of course Nato plans for Ukraine are a direct threat to Russian citizens.”

His views were both surprising and enlightening as to the very different narrative put out by the Kremlin, compared to the way it’s viewed in the West. To European and Western ears, these pronouncements sound almost unfathomable, even amounting to a blatant disregard for carefully documented evidence. Yet these are just some of the beliefs held not only by Kremlin supporters in Russia and across the wider population there but also in several other parts of the world.

After Russia launched its invasion of Ukraine on 24 February, the UN held an emergency vote – 141 nations out of 193 UN member states voted a week later to condemn it. But a number of major countries chose to abstain, including China, India and South Africa. So it would be delusional for Western leaders to believe that the entire world shares Nato’s view – that Russia is entirely to blame for this catastrophic war – because it doesn’t.

There are many reasons, ranging from straightforward economic or military self-interest, to accusations of Western hypocrisy to Europe’s colonial past. There is no one-size-fits-all. Every country may have its own particular reasons for not wanting to publicly condemn Russia or alienate President Putin.

‘No limits’ to co-operation

Let’s start with China, the world’s most populous state with more than 1.4 billion people, most of whom get their news on Ukraine from the state-controlled media, just as most people do in Russia. China received a high-profile visitor to its Winter Olympics shortly before the Ukraine invasion began on 24 February – President Putin. A Chinese communique issued afterwards said there “was no limit to the two countries’ co-operation”. So did Putin tip off his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping that he was about to launch a full-scale invasion of Ukraine? Absolutely not, says China, but it’s hard to imagine that there would have not been even just a hint of what was to come to such an important neighbour.

China and Russia may one day end up being strategic rivals, but today they are partners and share a common disdain, bordering on enmity, for Nato, the West and its democratic values. China has already clashed with the US over Chinese military expansion into the South China Sea. Beijing has also clashed with Western governments over its treatment of its Uighur population, its crushing of democracy in Hong Kong and its frequently repeated vow to “return Taiwan to the fold”, by force if necessary.

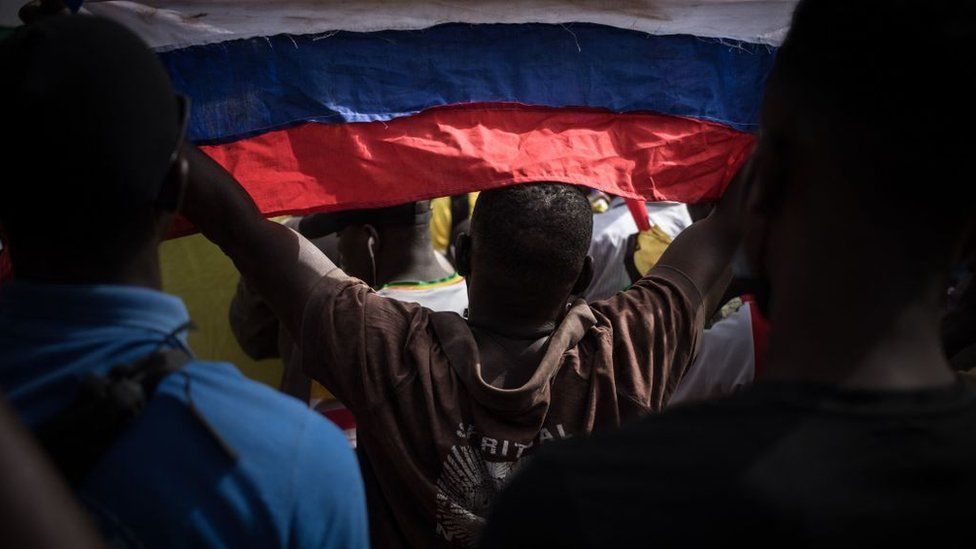

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGESSo China and Russia have a common enemy in Nato, and their governments’ worldview percolates down to both countries’ populations with the result that, for the most part, they simply do not share the West’s abhorrence of Russia’s invasion and alleged war crimes.

India and Pakistan have their own reasons for not wanting to antagonise Russia. India gets much of its arms from Moscow and, after its recent clash with China in the Himalayas, India is betting that one day it may need Russia as an ally and protector.

Pakistan’s recently ousted Prime Minister, Imran Khan, has been a fierce critic of the West, especially the US. Pakistan also receives arms from Russia and it needs Moscow’s blessing to help secure trade routes into its northern hinterland of Central Asia. Prime Minister Khan went ahead with a pre-planned visit to see President Putin on 24 February, the very day Russia invaded Ukraine. Both India and Pakistan abstained in the UN vote to condemn the invasion.

Hypocrisy and double standards

Then there is the accusation, shared by many, especially in Muslim-majority countries, that the West, led by its most powerful nation – the US – is guilty of hypocrisy and double standards. In 2003, the US and UK chose to bypass the UN – and much of world opinion – by invading Iraq on spurious grounds, leading to years of violence. Washington and London have also been accused of helping to prolong the civil war in Yemen, by arming the Royal Saudi Air Force which conducts frequent airstrikes there in support of the country’s official government.

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGESAnd where does the Middle East stand on this? No surprises that Syria – along with North Korea, Belarus and Eritrea – has backed Russia’s invasion. Syria’s President Bashar Al-Assad relies heavily on Russia for his survival after his country risked being overrun by ISIS fighters in 2015. But even long-time Western allies, like Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) although they backed the UN vote, have been relatively muted in their criticism of Moscow. The UAE’s de facto ruler, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed, has a good relationship with Vladimir Putin – his previous ambassador to Moscow has been on hunting trips with him.

It is also worth remembering that Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman has a largely dysfunctional relationship with President Biden. Such is their mutual dislike, that the two men reportedly refuse to take each other’s phone calls. Before that, when the world’s leaders gathered in Buenos Aires for the G20 Summit – in late 2018, just weeks after the West accused the Saudi crown prince of ordering the grisly murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi – most Western leaders gave the Saudi prince the cold shoulder. Putin, by contrast, high-fived him. That’s not something the Saudi leader will have forgotten in a hurry.

None of this means that all those countries mentioned actively support this invasion, apart from Belarus. Only five states voted in favour of it on 2 March at the UN, and one of those was Russia. But what it does mean is that, for multiple reasons, the West cannot assume the rest of the world shares its view of Putin, nor of the sanctions, nor of the West’s willingness to openly confront Russia’s invasion with ever more lethal supplies of weaponry to Ukraine.