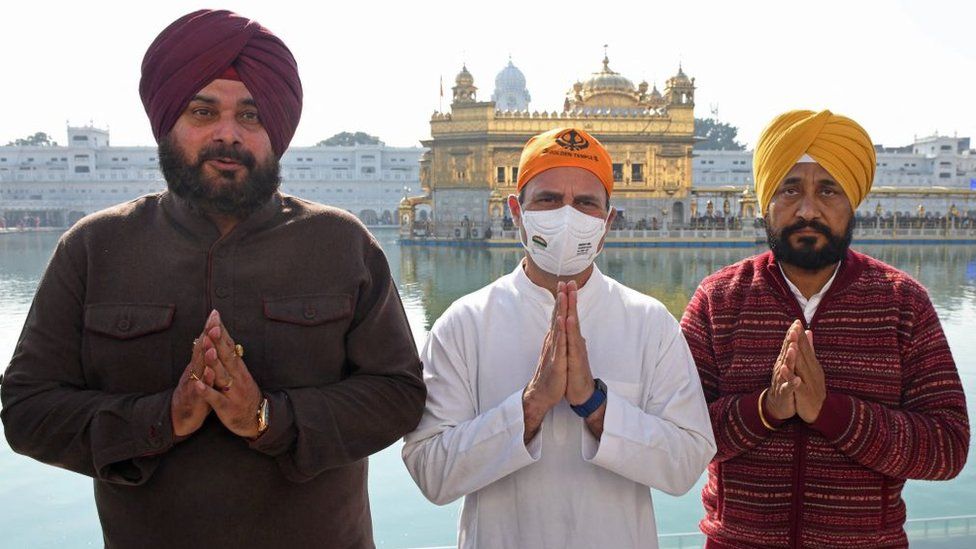

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGES Image caption, Charanjit Singh Channi is the face of the Congress in Punjab

By Atul Sangar

Editor, BBC News Punjabi

Does this choice – in the wake of months of in-fighting – mean that the Congress has succeeded in bringing its divided fold together?

Mr Channi, the 58-year-old low-profile leader from the Dalit (formerly Untouchables) community, was handpicked for the top job four months ago by the Gandhis – Congress party president Sonia Gandhi, her son and MP Rahul Gandhi, and daughter Priyanka Gandhi Vadra. (Together they are known as the party “high command”).

He succeeded Amarinder Singh, a veteran Congress leader who led the party to an impressive victory in the last election. Mr Singh left the Congress and is now a bitter opponent who has tied up with the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which is in opposition in the state.

The events leading up to Amarinder Singh’s resignation and Mr Channi’s selection left many bruised egos in the Punjab Congress – chief among them was Navjot Singh Sidhu, an unpredictable cricketer-turned-politician who threatened to quit as the party’s state chief after Mr Channi’s appointment.

“The visuals of Mr Channi, Mr Sidhu and Mr Gandhi warmly embracing each other on the stage did send a positive message,” says Jagtar Singh, a political observer.

The Congress hopes this will help establish Mr Channi’s authority as the first amongst equals and help him focus on campaigning without having to fend off attacks from his own colleagues.

The party faces an uphill task to retain power in the state, just one of three where it is currently governing.

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGESIts main rivals are the Aam Aadmi Party or AAP, which impressively became the main opposition party in its debut in the state in 2017, the regional Shiromani Akali Dali (SAD) and a BJP-led coalition.

Also in the fray are former CM Mr Singh and candidates backed by the Sanyukt Samaj Morcha, an alliance of 22 farmer unions, which took shape after the massive farmers’ protests that lasted for more than a year.

“Punjab wants to be led by one who has seen poverty and understands the poor,” he said.

In his more than four months in power, Mr Channi has announced several welfare measures and projected himself as a common man whose heart beats for the ordinary Punjabi.

He was successful to come extent – AAP felt threatened enough to focus its energies on calling his promises out.

The opposition got some ammunition from a recent raid by the Enforcement Directorate, a federal agency that fights financial crime, on Mr Channi’s nephew over allegations of sand mining – the agency also seized cash from his premises.

Mr Channi told the BBC that there is an attempt to “politically damage” his reputation.

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGESBut the bigger challenge might well be Mr Sidhu. Without naming names, he has said that dole and freebies aren’t the answer for Punjab’s young people. He has also floated his own “Punjab model” – a roadmap that, he claims, can rid the state of systemic corruption by politically-connected cartels and replenish the exchequer by tackling pilferage of resources, thereby enabling the government to launch social welfare measures and provide jobs.

With Sunday’s announcement, however, the Congress leadership has clearly thrown its weight behind Mr Channi. Will it work?

His appointment in September was seen as politically astute one amid a crisis – it led to fracturing of the power held by the Jat Sikh community for most of the time since the state’s creation in 1966, and also to appeal to the Dalit votes.

But while Dalits form 32% of Punjab’s population and there are signs of them consolidating in favour of the Congress in some areas, the community is not a monolith.

The Congress has traditionally received support from upper-caste Hindus in urban areas and, in the last election, from many Jat Sikhs as well. And these voters may not be too happy with the party overtly wooing the Dalit vote.

“This time, the Congress has given primacy to the Dalit vote and its politics in Punjab is veering from inclusive to an exclusive one,” says Dr Pramod Kumar, a social scientist who follows Punjab politics.

Many analysts feel that the Congress would have been more successful if it had a leader at the helm who could appeal not just to a core voting segment but also be acceptable to other sections of the population.

Despite his partial success in making the ordinary Punjabi identify with him, Mr Channi will take time to become such a leader.