IMAGE SOURCE, NEOM.COM Image caption, A Neom ad promises the city will be like a playground

By Merlyn Thomas and Vibeke Venema

BBC News

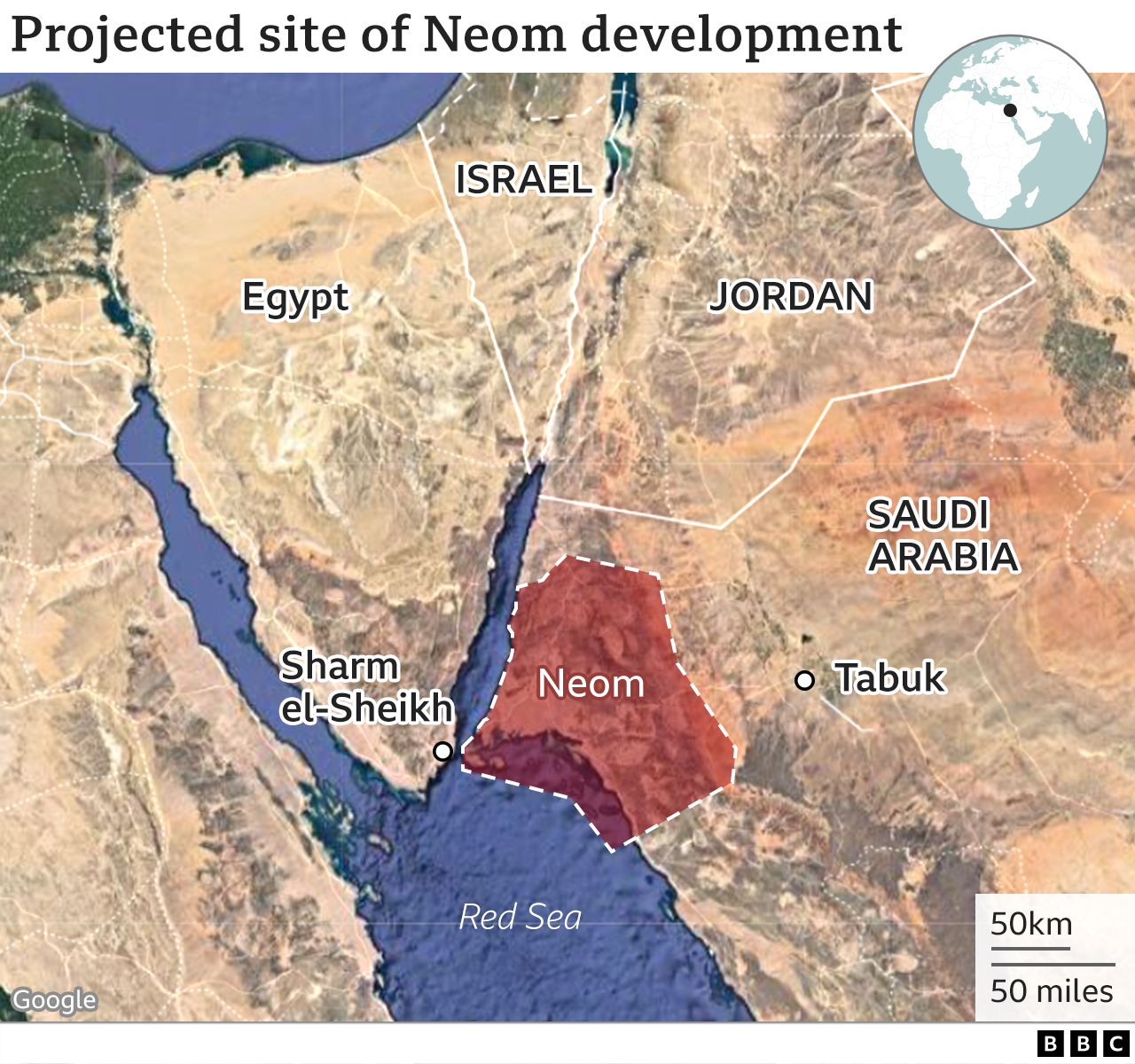

Neom claims to be a “blueprint for tomorrow in which humanity progresses without compromise to the health of the planet”. It’s a $500bn (£366bn) project, part of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 plan to wean the country off oil – the industry that made it rich.

Covering a total area of over 26,500 sq-km (10,230 sq-miles) – larger than Kuwait or Israel – Neom will, developers claim, exist entirely outside the confines of the current Saudi judicial system, governed by an autonomous legal system that will be drafted up by investors.

Ali Shihabi, a former banker now on Neom’s advisory board, says the mega-territory will include a 170km (105m) long city, called The Line, which will run in a straight line through the desert.

If that sounds unlikely, Shihabi explains that The Line will be built in stages, block by block. “People say this is some crazy project that’s going to cost gazillions, but it’s going to be built module by module, in a manner that meets demand,” he says.

Much like Barcelona’s traffic-free “superblocks“, he explains that each square will be self-sufficient and contain amenities such as shops and schools so that anything people need will be a five-minute walk or cycle away.

When complete, travel along The Line will be via hyper-speed trains, with the longest journey “never more than 20 minutes”, the developers claim.

What’s more, Neom will be home to Oxagon, a city floating on water spanning 7km (4.3 miles) – making it the largest floating structure in the world. Neom’s chief executive, Nadhmi al-Nasr, has said the port city will “welcome its first manufacturing tenants at the beginning of 2022”.

IMAGE SOURCE, NEOM.COM

IMAGE SOURCE, NEOM.COMFurther up the Red Sea coast from this “industrial hub”, Neom has announced plans for the world’s largest coral reef restoration project. Its website, which sometimes sounds like something out of a sci-fi novel, claims that the first phase of the mega-territory will be completed by 2025.

That’s the vision. The reality, for now, is more modest.

A satellite image currently shows that a single square has been built in the desert. As well as rows of homes, it has two swimming pools and a football pitch. Ali Shihabi says this is the camp for Neom staff, but we are not on the ground to verify.

IMAGE SOURCE, GOOGLE EARTH

IMAGE SOURCE, GOOGLE EARTHBut how feasible is it to build a cutting-edge city that lives up to its green credentials in the middle of the desert?

Dr Manal Shehabi, an energy expert at the University of Oxford, says that when evaluating how sustainable Neom can be, there are many things to consider. Will food be produced locally in a system that doesn’t use an excessive amount of resources or will it rely on food imports from abroad?

The website claims that Neom will become “the world’s most food self-sufficient city”. It sets out a vision for vertical farming and greenhouses – revolutionary for a country that currently imports about 80% of its food. There are questions about whether this can be done sustainably.

IMAGE SOURCE, YOUTUBE/NEOM

IMAGE SOURCE, YOUTUBE/NEOMCritics accuse the Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman, the driving force behind Neom, of greenwashing – making grand promises about the environment to distract from reality.

The “giga-project” is part of the crown prince’s vision of a greener Saudi Arabia. A week before the COP26 climate change negotiations he also launched the Saudi Green Initiative, announcing a target of achieving net zero emissions by 2060.

That was initially seen as a major step forward in the climate community, but it didn’t stand up to scrutiny, says Dr Joanna Depledge, an expert on the international climate change negotiations from the University of Cambridge. She points out that in order to limit warming to 1.5C, global oil production needs to fall by roughly 5% a year between now and 2030.

Yet Saudi Arabia promised to increase oil production just weeks after making headline green pledges for this year’s COP26 climate conference. The energy minister Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman reportedly said the Saudis wouldn’t stop pumping: “We are still going to be the last man standing, and every molecule of hydrocarbon will come out.”

IMAGE SOURCE, YOUTUBE/NEOM

IMAGE SOURCE, YOUTUBE/NEOM“I think it’s really quite shocking that Saudi Arabia still seems to think that it can continue to exploit and extract this oil in this current context,” says Dr Depledge.

A country’s emissions come from the fuel it burns, rather than the fuel it produces. So if a country like Saudi Arabia produces millions of barrels a year, and ships them abroad to other countries, the kingdom doesn’t have to count them.

Even domestically, Saudi Arabia has a long way to go – although its latest target aims for 50% of electricity to be generated with renewable energy by 2030, only about 0.1% of electricity was generated this way in 2019.

‘Creative thinking’

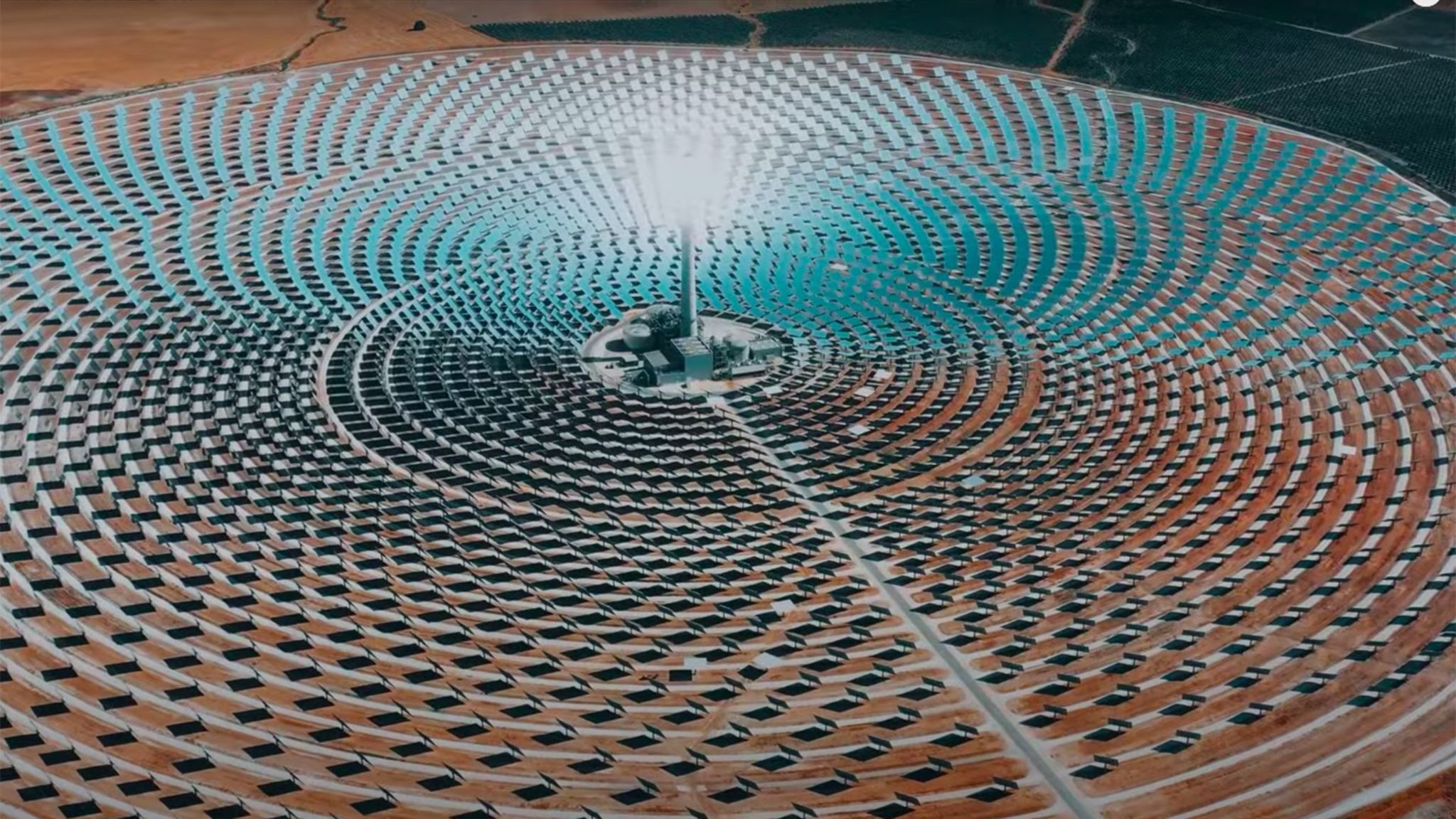

Defenders of Neom say it’s necessary to start afresh and build a smart, sustainable city powered by wind and solar, with water provided by carbon-free desalination plants.

“Saudi Arabia needs some creative thinking, because the Middle East is running out of water,” says Ali Shihabi of Neom’s advisory board.

Saudi Arabia is an arid country and about half of its water is produced through desalination plants – an industrial facility that takes away salt from water – powered by fossil fuels. It’s an expensive process and the by-product, a slurry of brine and toxic chemicals, is disposed of back in the sea, with detrimental consequences for marine ecosystems.

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGESNeom’s desalination process will be fuelled by renewable energy and the brine, rather than dumped back into the sea, will be used as an industrial raw material. There’s only one hitch – using renewable energies with desalination plants has never been successful.

Shihabi admits that Neom “is a pilot experimental project – but if we can solve the water problem in the Middle East, if just this project works, everything Neom has done is worthwhile”.

But climate experts are concerned that relying on unproven technologies can be a form of climate delay, getting in the way of significant action against the effects of climate change. It’s sometimes described as “technological optimism“.

And there are big questions about who Neom is for.

The desolate terrain between the Red Sea coast and the mountainous Jordanian border may have seemed like the perfect blank canvas to build a mini-state. However, there are people already living there – members of the ancient and traditionally nomadic Bedouin Huwaitat tribe. The project promises to create jobs and generate wealth in this underdeveloped region, but so far the local population haven’t seen any benefits.

Human rights campaigners say that two towns have been cleared and 20,000 members of the Huwaitat forcibly removed, without adequate compensation, in order to build the megacity. “The efforts to forcibly displace the indigenous population is one that breaches every norm and rule of international human rights law,” says Sarah Lea Whitson, executive director of Democracy for the Arab World Now.

One man was even killed. In April 2020, Abdulrahim al-Huwaiti refused to be evicted from his home in Tabuk and began posting videos online. Days later, he was shot by Saudi security forces – as he had predicted would happen.

IMAGE SOURCE, YOUTUBE

IMAGE SOURCE, YOUTUBEThe Saudi embassy’s spokesperson in Washington DC, Fahad Nazer, disputes the allegations of forced removal of the Huwaitat, although he did not dispute the killing of Mr al-Huwaiti, dismissing it as a “minor incident”.

Tourists and the rich

Neom’s slick public relations efforts – part of an effort to attract tourists to diversify the Saudi economy – have also opened it to criticism. Flashy promotional videos show all the glitz and glamour of a cosmopolitan city with its own laws and security forces, a territory independent of the old guard that rules Saudi Arabia.

But critics say the project will mostly cater to the very rich. Palaces have reportedly been built for the country’s royal family. Satellite images show a helipad and a golf course among the first construction projects.

IMAGE SOURCE, GOOGLE EARTH

IMAGE SOURCE, GOOGLE EARTHAli Shihabi claims the city will house everyone “from labourers to billionaires”, although he admits that’s not how it has been perceived.

“I think the problem with Neom is that it has failed in its communication strategy,” he says. “People think that it’s just a rich man’s toy.”

Tough choice

“Beginning this journey to a greener future has not been easy, but we are not avoiding tough choices,” Mohammed bin Salman has said. “We reject the false choice between preserving the economy and protecting the environment.”

Neom is clearly part of this vision. But so far the Saudis are avoiding the toughest choice of all – moving away from producing fossil fuels.

Turning off the taps will be hard, says Manal Shehabi, the Oxford University energy expert. “I think it would be very difficult from an economic perspective to expect any country that depends this much on oil and gas, to all of a sudden stop using it and stop exploiting the resources that it has.”

The Saudis say they are responding to the world’s energy needs. “The reality is that the demand for hydrocarbons around the world is still there,” says Saudi embassy spokesman Fahad Nazer.

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGESBehind the scenes, the Saudis and other fossil fuel-dependent countries have consistently tried to water down language around international climate commitments, says Dr Depledge.

This continued at COP26. “Saudi Arabia was intervening really quite intensively trying to point out uncertainties, costs, natural impacts, to play down the urgency of the climate change problem,” says Dr Depledge, who followed the negotiations in Glasgow closely.

“This is very much the kind of rhetoric and the kind of language that Saudi Arabia has been promoting since the very beginning of the climate change negotiations.”

But Fahad Nazer, the government spokesman, denies allegations of greenwashing and insists that Saudi Arabia is heading towards a green future.

And though questions remain about whether Neom will live up to its promises, Ali Shihabi invites us to reserve a condo on The Line, “before anybody else does”.

Listen to The truth behind Saudi’s eco-city from Trending on the BBC World Service