GETTY IMAGES

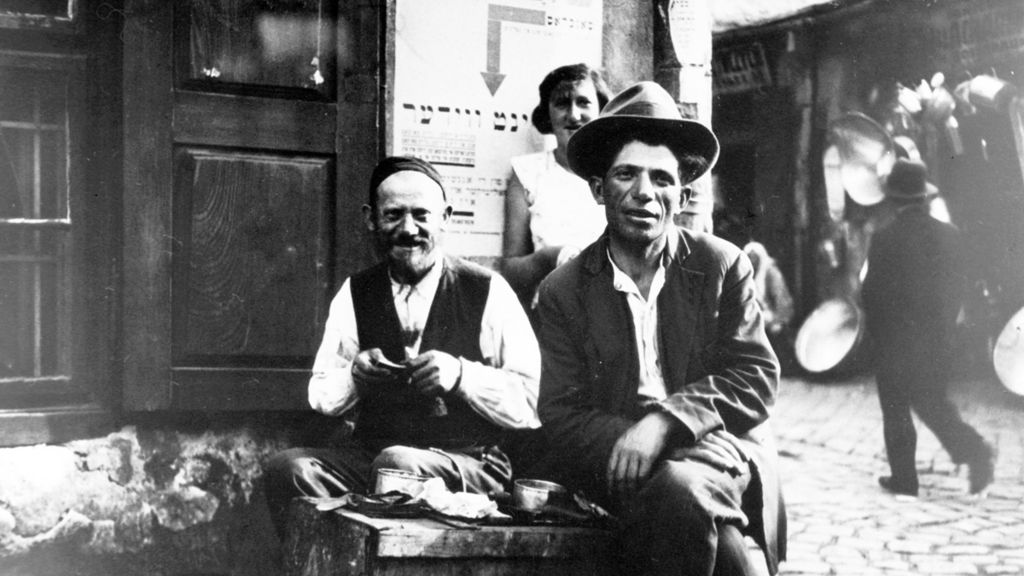

Even when the spring sunlight fills the little park, it remains an unsettling place. The Jewish world commemorated at Arsenalna Square in central Lviv was destroyed by genocide. The people who worshipped at the Golden Rose synagogue were either exiled or killed. There is no escape from history here. It is present in the memorial stones for the dead and in the void left by a murdered generation.

In western Ukraine’s biggest city, the past collides with the present in other ways too. You can hear it in the rattle of today’s refugee suitcases being pulled across the same cobblestoned streets where, in the high summer of 1941, the Germans and their Ukrainian collaborators chased Jews to their deaths. The photos of those days are some of the most terrible of the Holocaust – women being stripped and beaten before jeering mobs, eyes wide in horror, mouths frozen in mid-scream.

We are not in the middle of a new world war, or a Holocaust, but the lessons for the world of that terrible conflict – and the promises made in its aftermath – have a relevance we cannot ignore today.

It was a reality framed in scathing terms by the Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky when he addressed the Security Council of the United Nations this week. He reminded his audience that the UN had been established in 1945 to guarantee peace after the horrors of World War Two.

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGESListing allegations of war crimes by Russian troops in Ukraine – summary killings, torture, rape – he called for the council to order a war crimes investigation.

“Are you ready to close the UN?” he asked. “Do you think that the time of international law is gone? If your answer is no, then you need to act immediately.”

The threat to the peace of Europe is greater now than at any time since the end of the Cold War in 1989. For nearly a month, I watched families flee westward from Lviv in trains, cars and buses as Russia waged war on their homeland. I listened to survivors from the besieged port of Mariupol talk of a hell on earth with bodies lying in the streets and the cityscape they knew, of shops, restaurants, the Hurov Park with its spectacular fountains, reduced to rubble.

Less than a year ago, I walked through the Hurov with Lyubov Vasilievna and Dominic, her two-year-old grandson. I have known Lyubov for eight years, since the day she was wounded and two other grandchildren – Nikita, 10, and Karolina, six – were killed at the war’s beginning in 2014 after Russian-backed forces staged a rebellion in eastern Ukraine against the Kyiv government.

The three of them had been out walking when a shell exploded. In hospital, Lyubov told me she blamed herself for their deaths. “I don’t know how I am going to survive this. The images of them are always in front of my eyes,” she said.

So, it was heartening to meet her again last year, in a time of relative peace, with a new grandchild. “I am smiling because I live for him now,” she told me. “I have someone to take care of. He brings me joy.”

Now, as Mariupol is being destroyed, I do not know what has happened to Lyubov and Dominic. I have called and called, but her phone no longer rings.

IMAGE SOURCE, MAXAR/ GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE, MAXAR/ GETTY IMAGESEvery day at Lviv railway station I watched for their faces in the crowds of refugees, but there was no sign. Lyubov and Dominic, and the dead Nikita and Karolina, are among many millions failed by history’s greatest broken promise. It was made in the aftermath of World War Two and is firmly rooted in the story of Lviv.

In the far western corner of Ukraine, Lviv is a city to remind us of the worst of mankind, but also of what can be done to protect us from the consequences of aggression.

Walk five minutes west from the ruins of the synagogue and you reach a squat two-storey building that was the cradle of the world’s most important human rights legislation – the very principles under which President Putin and his armies might yet face judgement.

The law faculty of the University of Lviv was the alma mater of Raphael Lemkin who invented the word genocide to describe the attempt to exterminate “in whole or in part” a national, religious or racial group. Aghast at the Nazi Holocaust Lemkin coined the term in 1944 and, four years later, succeeded in having the UN define genocide as a crime under international law.

His fellow alumnus, Hersch Lauterpacht, was instrumental in bringing about the legal concept of crimes against humanity which was first used to prosecute Nazi leaders at the Nuremberg trials in 1945-46.

Both men were Jewish and studied in Lviv in the early decades of the 20th Century. Lviv was called Lemberg then and was a city of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, home to a cosmopolitan mix of Poles, Ukrainians, Russians and other nationalities from across the empire.

World War One destroyed Austria-Hungary and ushered in an age of instability as Poles, Ukrainians, the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany fought for control of the city. The majority of the remaining Jewish population was wiped out in the Holocaust, among them the relatives of Lemkin and Lauterpacht.

IMAGE SOURCE, ALAMY

IMAGE SOURCE, ALAMYAt the end of World War Two, Lviv came under the rule of the Soviet Union, where it remained until the fall of communism and the creation of an independent Ukraine in 1991.

Although they differed in important respects – Lemkin argued in favour of group protections, Lauterpacht focused on individual rights – their legacies were enshrined in the 1945 UN Charter, which promised to “save succeeding generations from the scourge of war which, twice in our lifetimes, has brought untold sorrow to mankind, and to reaffirm faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person…”

Now, Lviv finds itself once more at the centre of a great historical trauma.

I think of that phrase – “the dignity and worth of the human person” – after watching people fight to board trains in the early days of the evacuation of Ukraine. I remember it when I see the images of executed civilians in Bucha, and I wonder what has happened to the dream of the lawyers from Lviv?

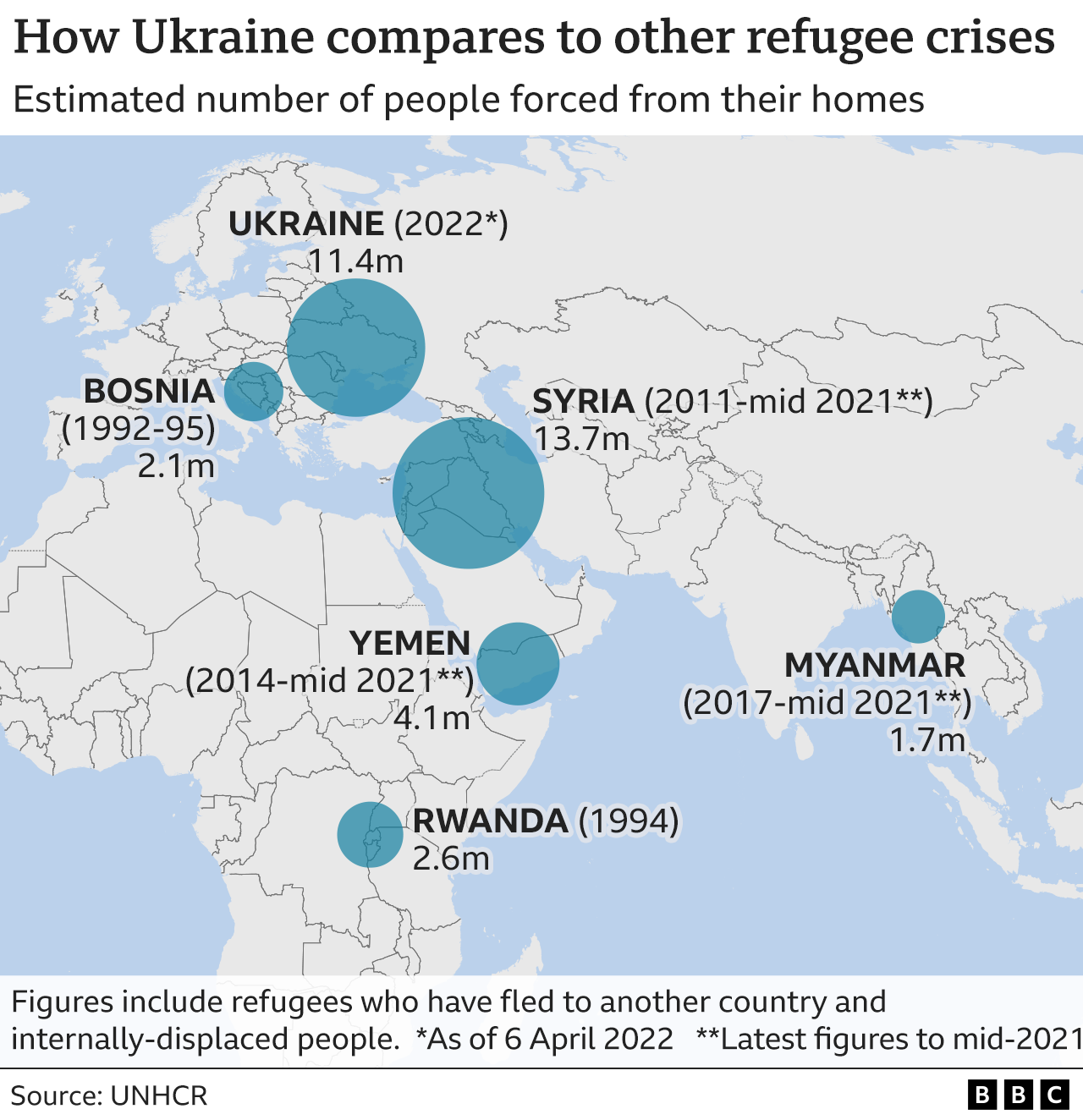

We are living in an age where millions are displaced by war. I have seen them jumping from smugglers’ boats into the shallows on a Greek beach, shouting with joy that “God is Great”. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, Myanmar and Yemen, I have heard civilian victims describe cruel military campaigns.

According to the most recent UN statistics – gathered before the Russian invasion of Ukraine – 84 million people are now forcibly displaced worldwide. The figures reflect an international order in crisis with the UN unable to prevent the murder and abuse of civilians in many regions of the world.

To understand how we have come to this point it is necessary to go back a little to one of the most terrible crimes of our modern era.

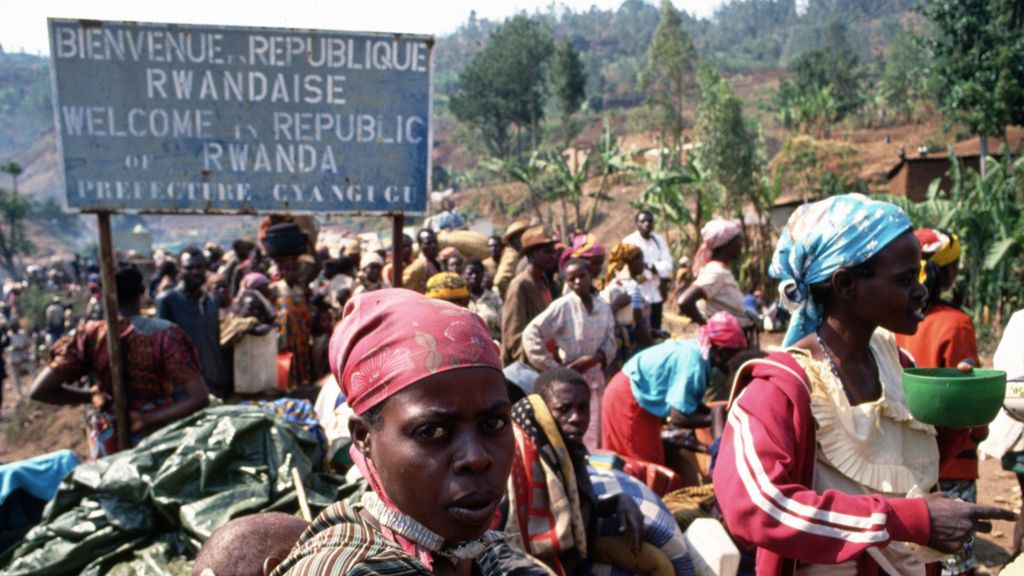

It all happened in Rwanda – genocide, crimes against humanity and mass rape as a weapon of war. In late spring of 1994, I was sent to the small, central African country that had become a vast open-air cemetery. The dead flowed down rivers. They lay piled up in churches. The smell of decomposing bodies hung over abandoned villages.

In the space of 100 days, up to 800,000 people are estimated to have been murdered in the Rwandan genocide. It also sparked one of the worst refugee crises in living memory.

Rwanda happened because a hate-filled elite decided that the solution to the country’s problems was to exterminate the Tutsi ethnic minority.

Two weeks into the genocide, with tens of thousands already slaughtered, the UN Security Council voted to reduce the peacekeeping force from over 2,000 members to 270. This came after 10 Belgian peacekeepers were attacked and killed by the Rwandan army. The great powers abandoned Rwanda to its fate.

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGES IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGESUnlike Ukraine now, Rwanda was a country with little geo-political importance. The US and other powers on the Security Council refused until it was too late to use the word coined by the Lviv lawyer, Raphael Lemkin, because describing the slaughter as “genocide” might have created a responsibility to intervene and protect the victims under Article 1 of the Genocide Convention.

I cannot ever forget the sight of Tutsi refugees huddled a few yards from me outside a municipal office in Butare – a city in southern Rwanda – surrounded by extremist militia and soldiers, and wondering if they would live or die. Many were ultimately slaughtered.

In July 1995, one year after the Rwandan genocide ended, Bosnian Serb forces under General Ratko Mladic murdered 8,000 men and boys when they overran the town of Srebrenica. It happened under the eyes of Dutch UN peacekeepers.

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGESThe two genocides of the 1990s – in central Africa and the former Yugoslavia – showed what happened when the Security Council was challenged to live up to words of the UN charter. The promise of 1945 was frustrated by lack of political will and division.

But those terrible years of the 1990s would come to have a profound effect on international law. If there was a failure to prevent genocide it could at least be punished. Tribunals were set up to try the accused of Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia. There were also courts to try those accused of responsibility for mass killings in Cambodia and Sierra Leone.

There were UN military operations to stop the killing of civilians in Sierra Leone and Nato forces intervened to end the expulsion of ethnic Albanians in Kosovo. Although, the latter provoked an ominous confrontation with Russia, an ally of Serbia and already wary of Nato encroachment to the east.

The world moved to establish a permanent court to try cases of genocide and crimes against humanity. The International Criminal Court – the ICC – was set up in 1998 to try the most serious cases of human rights abuses. It is not part of the UN but was created by UN members and works closely with the organisation.

In 2009, in a landmark moment, President Omar al-Bashir of Sudan, became the first sitting head of state to be indicted for genocide by the ICC, for the killing of civilians in Darfur.

Just as at the end of WW2, the idea was that prosecutions might not only provide accountability but would make future war leaders think twice before abusing the rights of civilians.

But there was a problem from day one, and it is one that shadows the current debate about war crimes in Ukraine.

Neither the US, China or Russia ratified the Rome Statute – the treaty that established the court. This means the three biggest military powers are not subject to ICC jurisdiction.

The only way they could be is if the Security Council votes to refer them. But as each nation has a veto, that is never going to happen. It means the ICC would be powerless if it wanted to indict President Putin and his senior generals for the crime of waging an aggressive war against Ukraine. Aggression was described by the Nuremberg tribunal after WW2 as “the supreme international crime differing only from other war crimes in that it contains within itself the accumulated evil of the whole”.

It is worth remembering what happened when the court tried to investigate alleged war crimes by all the parties in Afghanistan. The Trump administration went as far as placing sanctions on the chief prosecutor of the ICC to signal its opposition to any judicial pursuit of US forces.

And – in China’s autonomous region of Xinjiang – an attempt to investigate Chinese officials for the alleged genocide against the Uyghurs failed because China was not an ICC member.

A lopsided international order – one rule for the weak, one rule for the strong – is ultimately not a sustainable legal order

The war crimes lawyer, Prof Philippe Sands QC, believes the attitude of the superpowers creates “lopsided justice” where the only prosecutions are those involving less powerful nations.

“One rule for the weak, one rule for the strong – is ultimately not a sustainable legal order or even really a legal order,” he says.

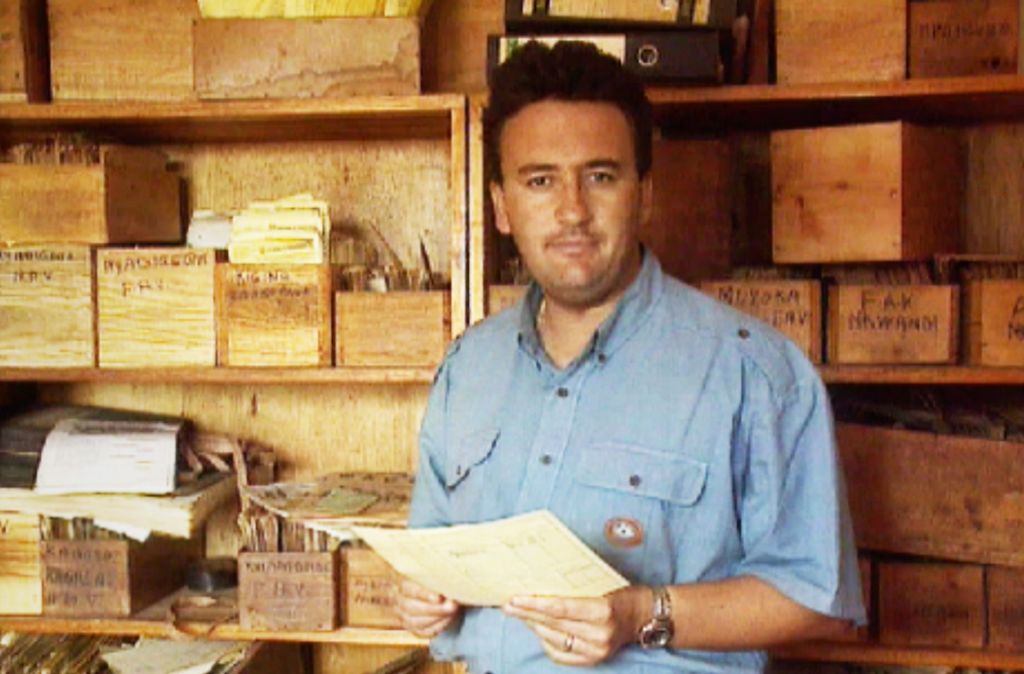

Prof Sands’ grandfather came from Lviv, and his great-grandmother was murdered by the Nazis. He is among those looking at the possibility of setting up a special international tribunal to indict the Russian president and his commanders.

But the legal framework is not the only issue that hangs over the current debate about the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Even some supporters of prosecuting President Putin acknowledge a charge of double standards against the US and the UK.

Prof Sands points out that the invasion of Iraq in 2003 by a US-led coalition polarised world opinion. The then UN Secretary General Kofi Annan would later call the invasion illegal. “You reap what you sow – and what you sow includes your own double standards,” he says.

The British and American governments insisted the invasion was legal.

But President Putin used the Iraq example as a rhetorical stick to beat the US and UK when he announced his decision to attack Ukraine, declaring that there was a “special place” for the invasion of Iraq – which had been carried out “without any legal grounds”.

In reality, there has never been a golden age of post-war peace guided by international diplomacy. The big powers have not fought an apocalyptic nuclear war but millions have died in wars big and small – in Korea, Algeria, Congo, Cambodia, Vietnam, Algeria, Indonesia, Angola, Ethiopia, Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Libya and many other battlegrounds. Some of those wars have been – at least partly – proxy conflicts between superpowers. More than 4,000 UN peacekeepers have lost their lives in different conflict zones trying to protect civilians and act as a buffer between warring parties.

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGESRather than being a place where the great powers consistently work for peace, the Security Council, too often, became a forum of superpower rivalry. Ukraine is just the latest dangerous example.

On 26 February, two days after the Russian invasion began, the Security Council met to discuss a resolution calling on Moscow to stop its attack and withdraw all troops. Russia vetoed that move for peace.

In a singularly ominous moment, President Putin implicitly threatened to use nuclear weapons to deter any intervention by Nato. Whether he intends to deploy nukes or not, the simple issuing of such a threat reflects the perilous state of human affairs in the 21st Century.

The current UN Secretary General, António Guterres, sounded almost forlorn when he declared: “We must never give up. We must give peace another chance.” But even some of those critical of the Security Council, argue that this can also be a moment of possibility – if, for example, a special tribunal can be set up to investigate a superpower like Russia for its actions.

“I am partly fearful but also partly optimistic,” says Prof Sands. “This period could destroy the [legal] order created by the 1945 moment [the defeat of Nazism] or it might develop and strengthen it. I am inclined to the latter view. It’s a long game. Two steps forward and one back, then another forward. We just have to stick to a principled approach.”

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGESThere have also been important signs of change at the UN in recent days. The General Assembly – the body made up of all 193 UN members – condemned the invasion and voted to remove Russia from the UN Human Rights Council. China voted against the move and India abstained – between them they represent a third of the world’s population. And while the decision doesn’t affect what the Security Council does or does not do, the moral signal from more than two thirds of UN members was clear.

One former UN official with experience of genocide and war crimes told me that it was a mistake to see the present world order solely through the lens of big power politics. Prof Mukesh Kapila of the University of Manchester is a former UN representative in Sudan and was instrumental in the campaign to have the killings in Darfur recognised as genocide.

“In the struggle between right and wrong, good and evil, there is a lot of activity. It is not all going on the side of the bad guys,” he says. He points to the case against Myanmar at the International Court of Justice – a UN court established in 1945 where one state can bring action against another. Myanmar is being pursued by the small west African nation of The Gambia for alleged persecution of the Rohingya Muslims.

Prof Kapila also cites the development in recent years of “universal jurisdiction” – where individual nations can try alleged war criminals from other countries if they arrest them on their soil. The successful German prosecution last January of a Syrian officer for murder, torture and sexual assault is recent example.

Calls for reform of the UN Security Council are not new. It has long been criticised for representing the imperial and superpower realities that prevailed at the end of WW2. There is no permanent representation for Africa, the Indian sub-continent or Latin America.

Expanding the UN’s top body would not at a stroke remove the potential for great power rivalry. But Prof Kapila suggests one way around the stalemates created by veto powers would be to strengthen the role of the General Assembly – the body that has just acted against Russia.

“If the Security Council is deadlocked, then why not create a mechanism where one member can take it to a bigger jury – the General Assembly. It is more democratic, and it also increases pressure on the Security Council to reach an agreement.”

There seems little prospect at the moment of the “Permanent Five” – China, France, Russia, the UK and US – agreeing to dilute their influence. “Turkeys don’t vote for Christmas,” as Prof Kapila puts it. But he argues that civil society movements have established powerful pressure for progress in recent years – in the area of climate change, for example. “Things which seem improbable now can become real.”

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGESAt the heart of the promise made in the UN Charter was the idea that countries must work together to avoid war. If armed conflict did break out they would send forces to try to keep the peace and the world would ensure abuses were prosecuted – both for the sake of justice and to deter future crimes.

It is possible – no more than that – that the crisis in Ukraine becomes one of those moments where the high stakes of conflict create a genuine moment of international reflection and generate a momentum for change. Before she stepped down from power, the German Chancellor Angela Merkel wistfully reflected on a world where unilateral action by states threatened peace and stability.

Mrs Merkel, who grew up in East Germany before the fall of the Berlin Wall and in the looming shadow of superpower rivalry, warned of the dangers of forgetting – especially as those with lived experience of WW2 died away.

“We have to take care now not to enter a historical phase in which important lessons from history fade away. We have to remind ourselves that the multilateral world order was created as a lesson from the Second World War.”

Remember where we have come from, was the message, and act so that we are not dragged backwards.

War in Ukraine: More coverage

- LIVE: Latest updates from Ukraine

- CHERNOBYL: Inside the nuclear plant after Russians left

- SPIES: Behind their attempts to stop the war

- ANALYSIS: Video appears to show killing of captive Russian soldier

- READ MORE: Full coverage of the crisis

-

Ukraine’s six weeks of devastation and defiance

1 day ago

-

Do Bucha civilian killings amount to genocide?

2 days ago

-

A dangerous escape on Ukraine’s ‘Rescue Express’

25 March

-

Children of the Soviet era running from Russia

9 March

-

For Ukraine’s Jews and Roma, war revives trauma

4 March

-

Pushchair passed over heads in desperate train station scenes

28 February