GETTY IMAGES BBC Trump wall: How much has he actually built?

By Lucy Rodgers and Dominic Bailey

BBC News

Building a “big, beautiful wall” between the US and Mexico was the signature promise of President Donald Trump’s 2016 election campaign. A concrete barrier, he said, would serve to stop what he described as a flow of illegal immigrants and drugs over the border.

But what actually happened to the wall? How much of it has been built? And how effective has it been?

1. How much ‘new wall’ Trump has built is up for debate

Any calculation of the miles of new wall constructed by Mr Trump and his administration depends very much on the definition of the words “new” and “wall”.

Before he took office, there were 654 miles (just over 1,000km) of barrier along the southern border – made up of 354 miles of barricades to stop pedestrians and 300 miles of anti-vehicle fencing.

Now, according to US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) in its 6 October status report, the southern border has 669 miles of “primary barrier” – the first structure people heading from Mexico to the US will encounter – and 65 miles of “secondary barrier” – which usually runs behind the primary structure as a further obstacle.

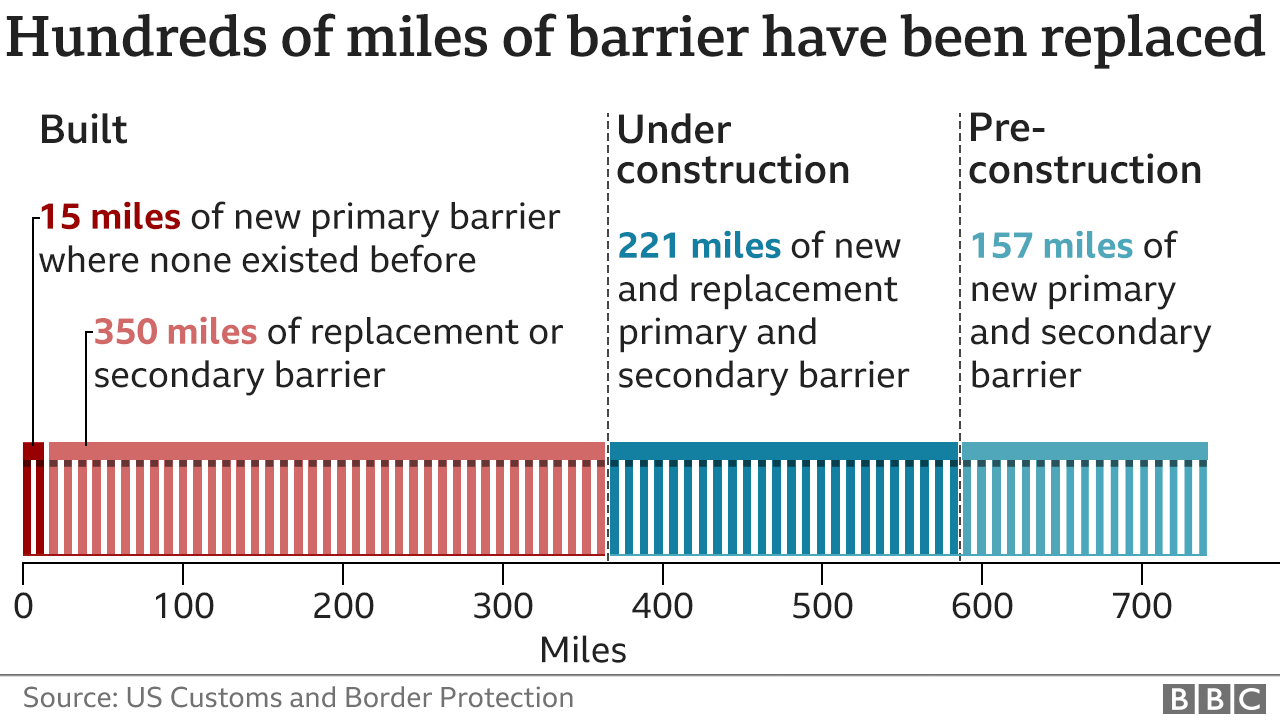

This means that in areas where no barricades existed before, they have built 15 miles of new, primary barrier or “border wall system”, as it is called by CBP.

About a further 350 miles of barrier has been built, according to CBP, made up of replacement structures and some new secondary barrier.

More is planned, too, with 378 miles of new and replacement barrier either under construction or in the “pre-construction phase”. Less than half of this will be in locations where no barriers currently exist, according to CBP.

However, Mr Trump himself doesn’t make a distinction between these new stretches of barrier and replacement structures, regarding both as new wall.

This is because, he says, replacements involve “complete demolition and rebuilding of old and worthless barriers”.

And he regards the progress made so far as a success.

“My administration has done more than any administration in history to secure our southern border,” Mr Trump said in June during a visit to the wall.

But what Mr Trump has actually built is far from what he promised at the start of his 2016 election campaign, when he pledged to build a concrete wall along the border’s entire 2,000-mile length.

He later clarified that it would cover only half of that. And by the time of his State of the Union address in February this year, his pledge had been reduced to “substantially more than 500 miles” by January 2021.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGESMr Trump is still short of that target – even if you include all the new, replacement and secondary barriers erected so far.

Yet how much more will be built is uncertain, with Democratic rival presidential candidate Joe Biden saying that, while he would not tear down the barrier Mr Trump has built, he would not expand it further.

2. Most of the wall isn’t ‘wall’ at all

As well as scaling back his ambitions for the length of the border barrier, Mr Trump has also changed his view of what constitutes a wall.

Throughout his 2016 election campaign, when he described it, he talked about concrete.

But once elected, he began referring to a barrier made of steel, which would enable border agents to see through it.

And what has been built so far is mostly such steel fencing.

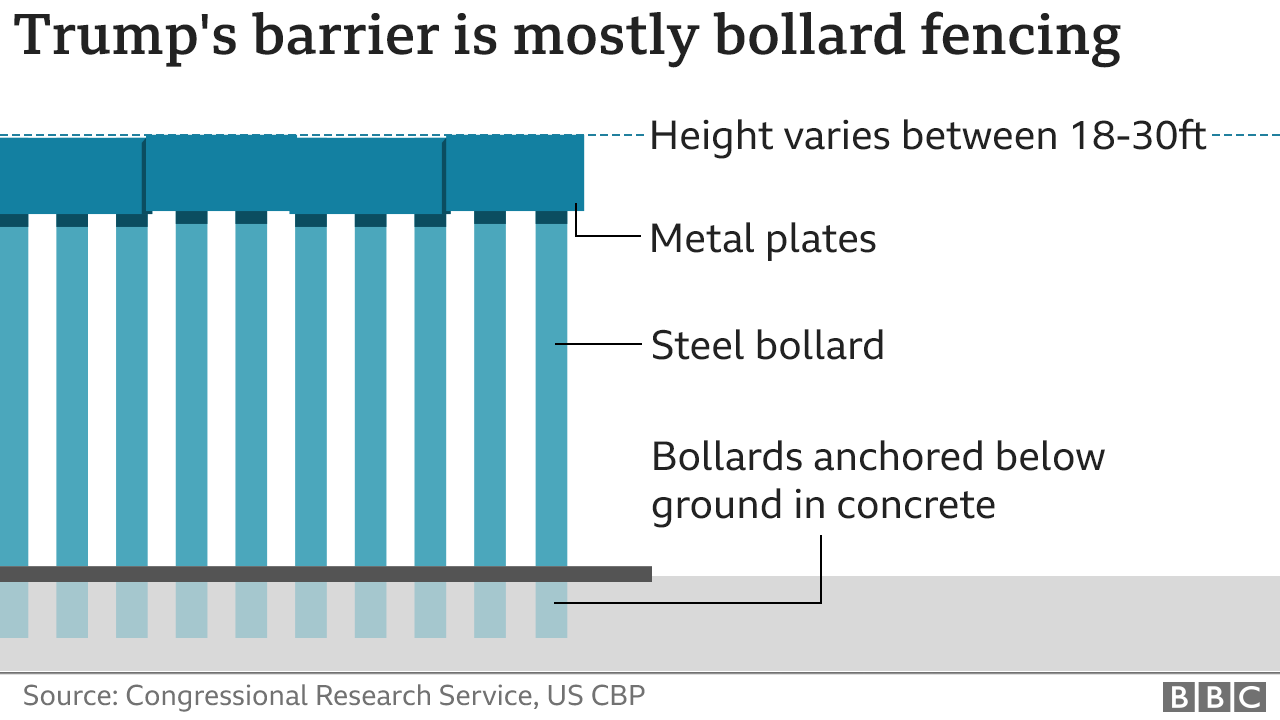

Specifically, much of the current wave of construction is 18-30ft (5.4-9m) reinforced bollard fencing, according to a report by the non-partisan Congressional Research Service.

“It poses a formidable barrier, but it is not the high, thick masonry structure that most dictionaries term a ‘wall’,” the report states.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGESHowever, the report adds that while the new barriers may not be made of concrete and in many cases replace existing structures, they do pose “a new obstacle that changes the calculus of those attempting to cross the border between ports of entry”.

Having said that, although Mr Trump’s barriers are not themselves made of concrete, they have been constructed using a significant amount of it, according to CBP.

Some 774,000 cubic yards (592,000 cubic metres) of concrete have been used in construction so far, alongside 539 tonnes of steel.

3. How it’s being paid for remains controversial

Despite Mr Trump’s pledge on the campaign trail in 2016 to get Mexico to pay for the wall, it is the US government that has spent billions of dollars to expand and reconstruct it.

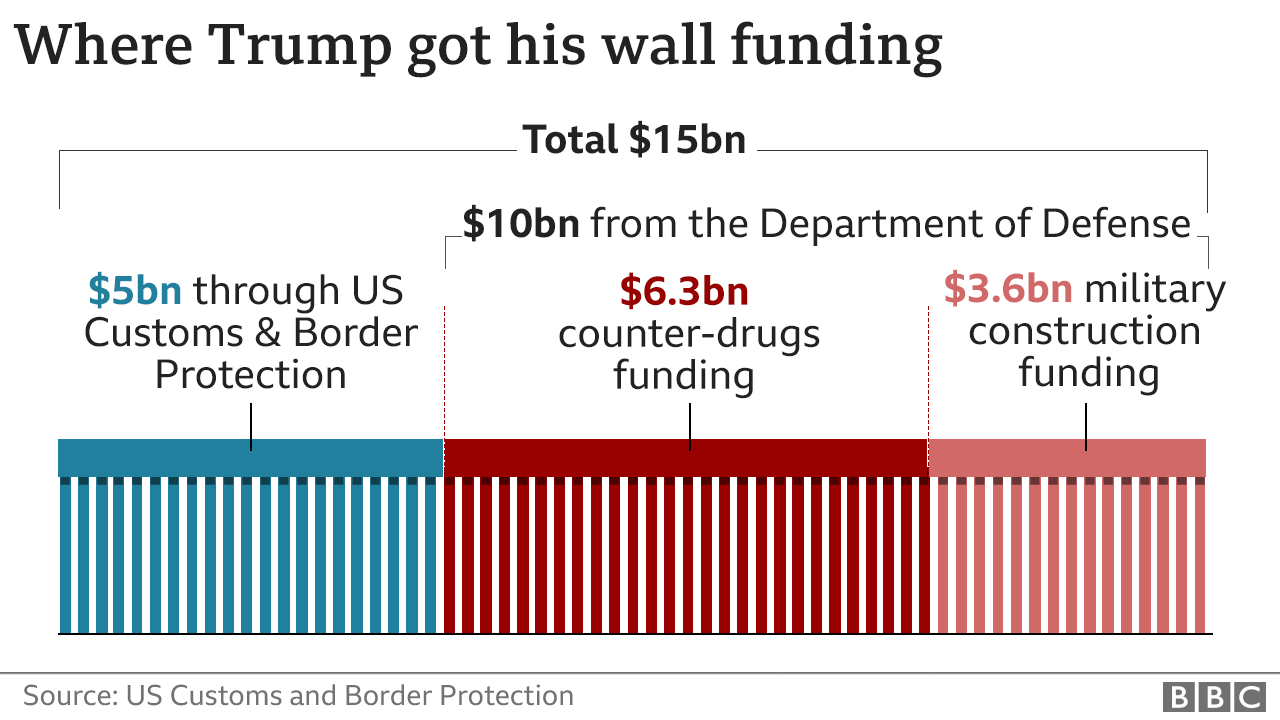

Just over $5bn (£3.9bn) in funding has come via traditional means through the CBP, but Mr Trump has also ordered almost $10bn in Department of Defense (DoD) funding to be diverted – a move that has sparked legal action.

Back in 2019, after his request for a further $5.7bn for the wall was rejected and Congress allotted only $1.4bn, Mr Trump declared border control a national emergency and used powers under the National Emergencies Act to move cash from DoD budgets.

Some $6.3bn of counter-drugs funding and £3.6bn of military construction funding has so far been diverted to the wall project, according to the CBP.

But Mr Trump’s decision to bypass Congress in this way has triggered a number of legal challenges – one from a number of environmental groups, represented by the American Civil Liberties Union, along with the states of California and New Mexico.

Two lower US courts have ruled in favour of these groups, concluding that the diversion of an amount of $2.5bn from DoD to construct barriers in California, New Mexico and Arizona was unlawful.

However, the Supreme Court – the highest federal court in the US – has allowed barrier construction using the funds to continue pending the appeals process. It will hear a challenge by President Trump’s administration against the lower courts’ decision next year.

Meanwhile, Democrats in the House of Representatives have also launched separate legal action.

4. Illegal crossings appear to have fallen this year

Mr Trump made reducing illegal immigration a top priority of his administration and it has been a key part of his re-election campaign.

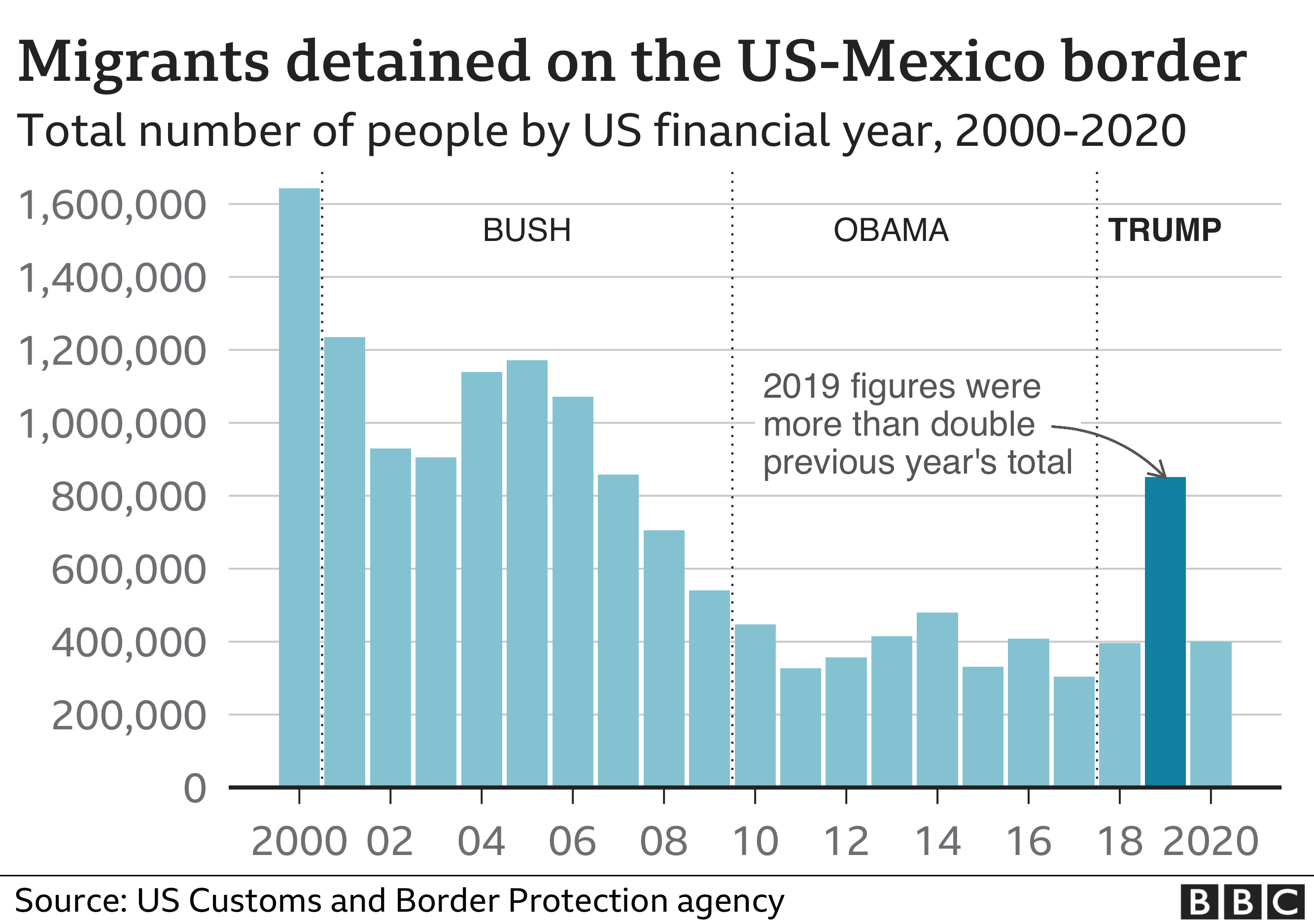

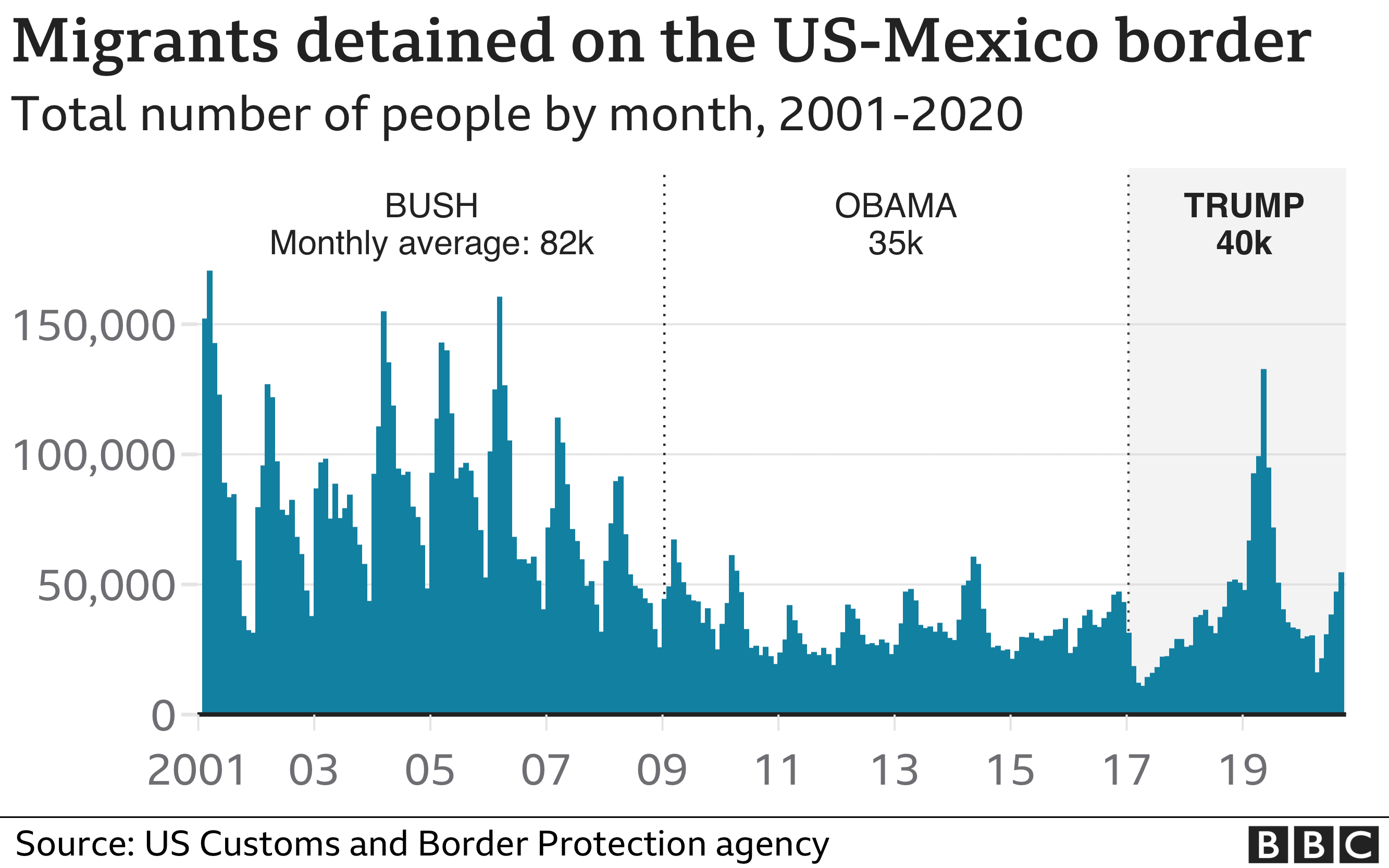

The latest figures suggest the number of migrants apprehended at the southern border this year have fallen after doubling between 2018 and 2019.

In particular, the number of children and those travelling in family groups apprehended at the border has dropped significantly in the 12 months to October, compared with the previous year.

How much this fall in numbers is down to the new barriers is unclear, though, and immigration experts say the drop is likely to be the result of the deterrent effect of a whole raft of anti-immigration measures introduced by Mr Trump’s administration rather than the barrier alone.

Those fleeing violence or persecution to the US have found asylum rules tightened, been forced to wait in camps for long periods as their cases are determined and come up against new limits on the number of refugees accepted into the country.

The administration has also adopted emergency procedures during the coronavirus pandemic that allow agents to expel those crossing the border back to Mexico, bypassing normal immigration and asylum proceedings.

“Any effect that the physical wall has had in reducing unauthorised migration has paled in comparison to the administration’s bureaucratic wall,” says Sarah Pierce, US immigration policy analyst at the independent Migration Policy Institute.

A series of “interlocking policies” have “significantly reduced unauthorised arrivals”, she told the BBC.

But although figures for detentions at the border are likely to have dropped for the year as a whole compared with 2019, monthly figures have been rising since the spring and reached a 13-month high in September.

This is driven partly by single adults from Mexico who have been trying to enter the US repeatedly, according to CBP figures. Data shows the “recidivism rate” – the number of repeat crossers – has risen by 37% since the end of March.

Mark Morgan, CBP’s acting commissioner, has suggested worsening economic conditions due to the coronavirus pandemic in Mexico and further afield could be to blame.

5. A key migrant camp is emptying

Thousands who have made the journey to the southern US border have found refuge in temporary border communities – often in shanty towns with little infrastructure or resources and vulnerable to pressure from violent organised-crime gangs.

According to Human Rights Watch, these migrants are under threat from criminal organisations which kidnap them on the assumption that they have relatives in the US who could be extorted for money.

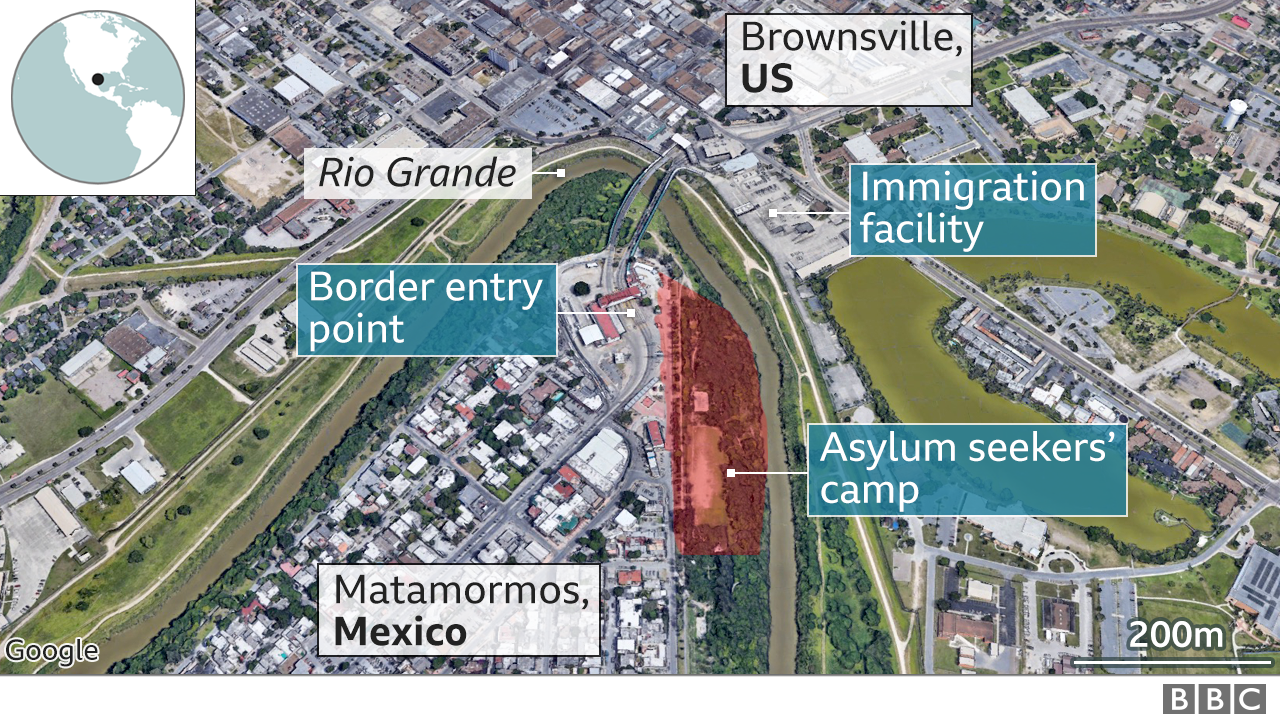

In the town of Matamoros, across the border from Brownsville, Texas, hundreds of people set up one such camp in 2018 near the entry point, in the scrubland on the banks of the Rio Grande.

By the start of this year, the camp had around 3,500 people living in tents – men, women, and children from across Central and South America and beyond. Another 10,000 asylum seekers are thought to be living elsewhere in the city.

Charities such as the World Food Kitchen, the Dignity Village collective and Global Response Management (GRM) provide food, tents, clothing and medical care to those living in the camp, where around 50% of residents are under the age of 15.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGESBut Andrea Leiner, director of strategic planning for GRM, says coronavirus and July’s Hurricane Hanna have had dire consequences.

Coronavirus restrictions have meant the border has been closed for all but essential travel and immigration hearings have been postponed.

Hurricane Hanna not only brought floods to the camp but also caused an infestation of rats, snakes and mosquitoes, forcing many residents to flee.

Ms Leiner says the repeated blows of plague, famine, and hurricane, on top of the legal restrictions, have drained people of hope.

“These people have nowhere to go. They can’t go home – they will be killed if they go home – and they can’t get into the US, so they are stuck in this purgatory right now and we don’t see that ending any time soon,” she says.

6. The barrier is unlikely to stop most kinds of drugs coming into the US

Mr Trump has claimed in the past that 90% of heroin in the US comes across the southern border and that a wall would help the fight against drugs.

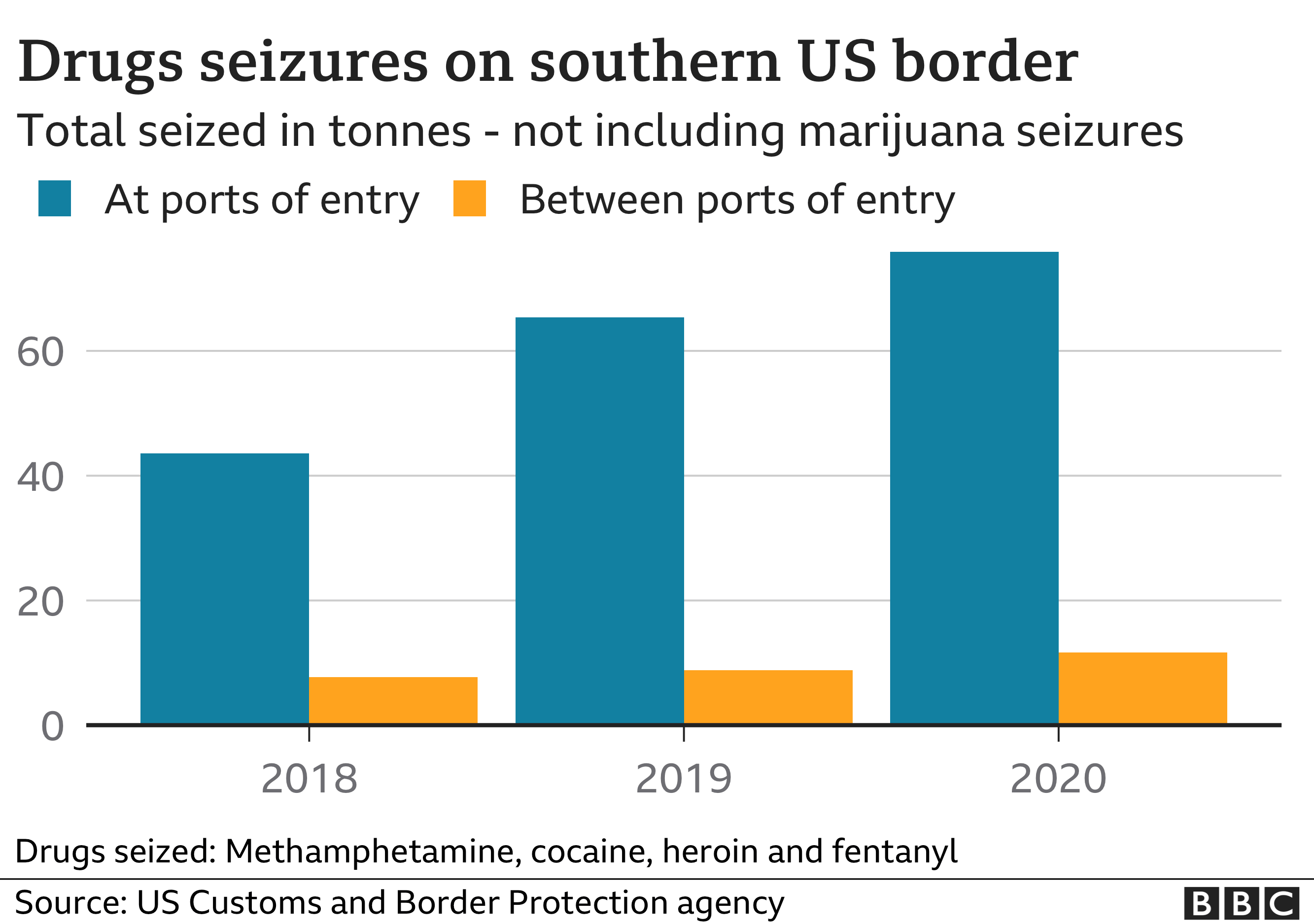

However strengthening and extending the border barrier is unlikely to do much to reduce illegal drugs – such as heroin, cocaine and methamphetamine – because most come through established border checkpoints, known as ports of entry.

While the majority of the heroin in the US does come from Mexico, the Drug Enforcement Administration says most of it is hidden in privately owned vehicles or transporter lorries, mixed with other goods, and smuggled through legal entry points.

CBP figures for drugs – excluding marijuana – seized on the southern border also show most come through ports of entry, although a report by the Congressional Research Service does state that border barriers can serve to push people to cross in places where they are more likely to be “detected, intercepted, and detained”.

Rodney Scott, chief of the US Border Patrol, agrees – and gives the example of San Diego, where he says cartel lorries used to drive across the border “three or four at a time on an almost daily basis, with high-speed pursuits throughout town”.

“Those stopped immediately with the border wall system, ” he says. “It does not mean cartels will stop smuggling drugs – now we’re going to deal with tunnels and other aspects – but it pushed that threat, the daily life-and-death threat for kids waiting for a school bus near the border, out of those areas.”

Smugglers also appear increasingly to be using boats to try to land drugs on the beaches of southern California – with the numbers intercepted by CBP’s air and marine operations jumping 82% last year.

Marijuana is the most trafficked drug, with more than 227 tonnes seized on the southern border this year. It is also the drug most likely to be smuggled in areas away from the border checkpoints.

Traffickers regularly use underground tunnels to smuggle tonnes of marijuana, mainly in the California and Arizona stretches of the border.

Design by Zoe Bartholomew and Gerry Fletcher