Aarogya Setu: Why India’s Covid-19 contact tracing app is controversial

- Home /

- Business /

- Aarogya Setu: Why India’s Covid-19 contact tracing app is controversial

Aarogya Setu: Why India’s Covid-19 contact tracing app is controversial

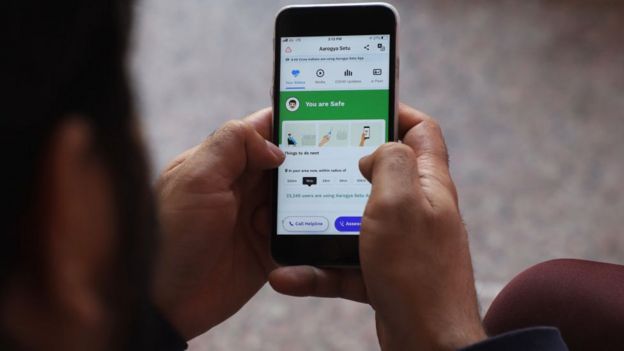

India’s Covid-19 contact tracing app has been downloaded 100 million times, according to the information technology ministry, despite fears over privacy.

The app – Aarogya Setu, which means “bridge to health” in Sanskrit – was launched just six weeks ago.

India has made it mandatory for government and private sector employees to download it.

But users and experts in India and around the world say the app raises huge data security concerns.

How does it work?

Using a phone’s Bluetooth and location data, Aarogya Setu lets users know if they have been near a person with Covid-19 by scanning a database of known cases of infection.

The data is then shared with the government.

“If you’ve met someone in the last two weeks who has tested positive, the app calculates your risk of infection based on how recent it was and proximity, and recommends measures,” Abhishek Singh, CEO of MyGov at India’s IT ministry which built the app, told the BBC.

While your name and number won’t be made public, the app does collect this information, as well as your gender, travel history and whether you’re a smoker.

Is it mandatory to download the app?

Prime Minster Narendra Modi has tweeted in support of the app, urging everyone to download it, and it’s been made mandatory for citizens living in containment zones and for all government and private sector employees.

Noida, a suburb of the capital, Delhi, has made it compulsory for all residents to have the app, saying they can be jailed for six months for not complying.

Food delivery start-ups such as Zomato and Swiggy have also made it mandatory for all staff.

But the government directive is being questioned by some.

- Coronavirus: How does contact tracing work and is my data safe?

- Coronavirus contact-tracing: World split between two types of app

- Coronavirus: India replaces ringing tone with health info

In an interview with The Indian Express newspaper, former Supreme Court judge BN Srikrishna said the drive to make people use the app was “utterly illegal”.

“Under what law do you mandate it? So far it is not backed by any law,” he told the newspaper.

MIT Technology Review’s Covid Tracing Tracker lists 25 contact tracing apps from countries around the globe – and there are concerns about some of them too.

Critics say apps such as China’s Health Code system, which records a user’s spending history in order to deter them from breaking quarantine, is invasive.

“Forcing people to install an app doesn’t make a success story. It just means that repression works,” says French ethical hacker Robert Baptiste, who goes by the name Elliot Alderson.

What are the main concerns about India’s app?

Aarogya Setu stores location data and requires constant access to the phone’s Bluetooth which, experts say, makes it invasive from a security and privacy viewpoint.

In Singapore, for example, the TraceTogether app can be used only by its health ministry to access data. It assures citizens that the data is to be used strictly for disease control and will not be shared with law enforcement agencies for enforcing lockdowns and quarantine.

“Aarogya Setu retains the flexibility to do just that, or to ensure compliance of legal orders and so on,” says the Internet Freedom Foundation, a digital rights and liberties advocacy group in Delhi.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESThe app builders, however, insist that at no point does it reveal a user’s identity.

“Your data is not going to be used for any other purpose. No third party has access to it,” Mr Singh of MyGov said.

The big issue with the app is that it tracks location, which globally has been deemed unnecessary, says Nikhil Pahwa, editor of internet watchdog Medianama.

“Any app that tracks who you have been in contact with and your location at all times is a clear violation of privacy.”

He is also worried by the Bluetooth function on the app.

“If I’m on the third floor and you are on the fourth floor, it will show that we have met, even though we are on different floors, given that Bluetooth travels through walls. This shows ‘false positives’ or incorrect data.”

What are the concerns over privacy?

The app allows the authorities to upload the collected information to a government-owned and operated “server”, which will “provide data to persons carrying out medical and administrative interventions necessary in relation to Covid-19”.

The Software Freedom Law Centre, a consortium of lawyers, technology experts and students, says it is problematic as it means the government can share the data with “practically anyone it wants”.

MyGov says “the app has been built with privacy as a core principle” and the processing of contact tracing and risk assessment is done in an “anonymised manner”.

Mr Singh says when you register, the app assigns you a unique “anonymised” device ID. All interactions with the government server from your device are done through this ID only and no personal information is exchanged after registration.

But experts have raised doubts about the government claim.

Mr Alderson has said there are flaws in the app which make it possible to know who is sick anywhere in India.

“Basically, I was able to see if someone was sick at the PMO [prime minister’s office] or the Indian parliament. I was able to see if someone was sick in a specific house if I wanted,” he wrote on his blog.

Aarogya Setu denied any such privacy breach in a statement.

But, India has “a terrible history” of protecting privacy, says Mr Pahwa, referring to Aadhaar – the world’s largest and most controversial biometrics-based identity database.

Critics have repeatedly warned that the scheme puts personal information at risk and have criticised government efforts to compulsorily link it to bank accounts and mobile phone numbers.

“This government has argued that privacy isn’t a fundamental right in court,” Mr Pahwa said. “We cannot trust it.”

India’s Supreme Court ruled in 2018 that the controversial Aadhaar scheme was constitutional and did not violate the right to privacy.

And the question of transparency?

Unlike the UK’s Covid-19 tracing app, Aarogya Setu is not open source, which means that it cannot be audited for security flaws by independent coders and researchers.

A senior IT ministry official told a newspaper that the government had not made the source code of Aarogya Setu public because it “feared that many will point to flaws in it and overburden the staff overseeing the app’s development”.

Mr Singh said “all applications are made open source ultimately and the same is applicable to Aarogya Setu also”.

Can you beat the system?

To register, users have to give their name, gender, travel history, telephone number and location.

“People can fill the form incorrectly and the government cannot verify it, so the efficacy of the data is questionable,” Mr Pahwa told the BBC.

According to a Buzzfeed report, an Indian software engineer had hacked the app to bypass the registration page, and even stopped the app from gathering data through GPS and Bluetooth.

The report also mentioned a comment on Reddit suggesting phone wallpaper as a simple workaround to not downloading the app.

“The privacy conscious are likely to do this. Those who don’t want to be forced to give their data to the government will look for and find workarounds. It could be by using a modified app or a screenshot, people will find ways,” Mr Pahwa says.

But Mr Singh argues that “if one is staying home and not meeting anyone, it would not matter whether they have the app, or deleted it or switched the Bluetooth off or lied on self-assessment”.