Political conflict is hardwired into the British system of government, but what happens when there is a national emergency that needs a unified response?

The gap between the front benches in the House of Commons is 3.96m – more than enough to comply with social distancing regulations.

But infection control was the last thing on the mind of the architects who laid out the chamber. The gap is traditionally said to be two swords’ length, to prevent MPs duelling with each other.

There were few signs of armed conflict breaking out at Prime Minister’s Questions on Wednesday, in an eerily quiet and sparsely populated chamber.

But it was a return to something like business-as-usual, with Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer putting the prime minister on the spot over the coronavirus crisis in care homes.

They got into a spat afterwards, which culminated in the prime minister reminding the leader of the opposition, in a letter, that the “the public expect us to work together” in the face of “this unprecedented pandemic”.

Is he right? Should the opposition parties swallow their pride and get behind the government? Or do they need to keep up the pressure and the criticism more than ever?

On being elected Labour leader, Sir Keir Starmer declared: “In the national interest, we will engage constructively with the government.”

He said he would not indulge in “opposition for opposition’s sake”.

Initially, some grassroots members and some of his own MPs felt that he hadn’t created enough dividing lines with the government – especially over social care.

But his first priority wasn’t to distance himself so much from Boris Johnson as from the previous Labour leader.

Starmer was well aware of Jeremy Corbyn’s unpopularity with some traditional Labour voters who – for the first time – defected to the Conservatives at the last election.

So as a step on the long journey to rebuilding trust, he made a point of saying things that you wouldn’t expect to hear from his predecessor.

It was only when Boris Johnson returned to front-line politics that Starmer’s “constructive criticism” emphasised the latter part of that phrase.

His tone was restrained not ranting – but the format of Prime Minister’s Questions played to his strengths as a lawyer.

He concentrated on his opponent’s apparent weakness – a lack of attention to detail.

He asked what would sound like reasonable questions to the wider electorate – but which, he assumed, his opponent would find difficult to answer.

Some Conservative MPs are now criticising him for “gotcha” politics – especially after challenging the prime minister over now-withdrawn care home guidance.

But looking beyond the immediate crisis, he sees his task as not only building up trust in his own party, but eroding it in the prime minister.

So far -on limited evidence – his approach doesn’t appear to be harming him.

One poll suggested he was marginally more trusted than Boris Johnson.

He has found it easy to ask searching questions of the government – but he has yet to set out extensively what Labour would do were the party in office.

He is in no rush to do so. As his predecessor might have discovered, “winning the argument” in opposition does not necessarily translate into winning an election.

While Sir Keir’s personal ratings have gone up, Labour is still languishing some way behind in the polls.

If he is to get to Number 10, he knows his will be a long-haul political journey.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Are the parties working together?

Boris Johnson has made an effort to keep opposition parties in the loop on key pandemic decisions, with regular briefings.

There is also some cross-party working on the government’s Cobra emergency committee, with Labour’s London Mayor Sadiq Khan, and the leaders of the Scottish, Welsh and Northern Irish administrations.

And government ministers have welcomed opposition input on measures to help people through the lockdown, such as extending statutory sick pay and more support for private renters.

Some cynics have suggested that one reason for cross-party working is that it will enable the PM to share the blame when things go wrong.

Others have criticised the opposition parties for being too negative and not coming up with solutions.

It is a dilemma for the Labour leader in particular, who is constitutionally obliged to oppose the government.

Why do we have an official opposition?

It’s not written down anywhere that the second largest party in the Commons has to systematically oppose everything the government does.

The convention emerged in the 19th Century, with the growth of two-party politics. The idea was to have an alternative government ready to step in when the governing party of the day was voted out.

In previous centuries, opposition to HM government, on anything other than private or local matters, was regarded as treason.

But as the Crown’s influence on Parliament weakened, and Britain’s democracy matured, it was seen as good practice to hold the government to account for its decisions.

And with the governing party’s MPs expected to be loyal, the job fell to what became known as the opposition, the party that had lost the most recent election.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESNevertheless, the leader of the opposition did not become a salaried position until 1937 and the idea of a formal shadow cabinet, a ready-made team of alternative minsters that meets regularly, did not get going until the 1950s.

Other countries have leaders of the opposition but surprisingly few have a shadow cabinet on the lines of the Westminster model, which is most closely followed in Australia, New Zealand and Canada.

There is no official opposition leader or shadow cabinet in America, although there have been informal efforts to set one up.

In the UK, smaller parties like the Liberal Democrats and the SNP, who also appoint shadow ministers, have often proved to be more effective than the official opposition, which has only ever been Conservative or Labour, since the early years of the 20th Century.

But the official opposition has a special status at Westminster, and is given more time, and public money, to hold the government to account – and to take centre stage every week at Prime Minister’s Questions.

A wartime coalition?

Some, such as Tory former minister George Freeman, have called for a cross-party “national government” to steer the country through the coronavirus emergency.

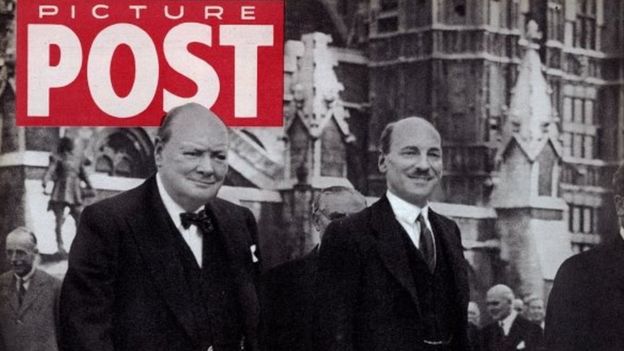

The wartime coalition government, formed in 1940, at a time when the UK was facing an existential threat from Nazi Germany, is often held up as an example of how to set aside political differences for the greater good.

Conservative Prime Minister Sir Winston Churchill drafted Labour leader Clement Attlee in as his deputy prime minister, and appointed other Labour, and Liberal, figures to cabinet positions, for the duration of the war.

There appears to be little appetite for something similar now, from either side.

Although Labour might take heart from the fact that Sir Winston’s solid, uncharismatic deputy went on to defeat the great war leader by a landslide in the 1945 election.