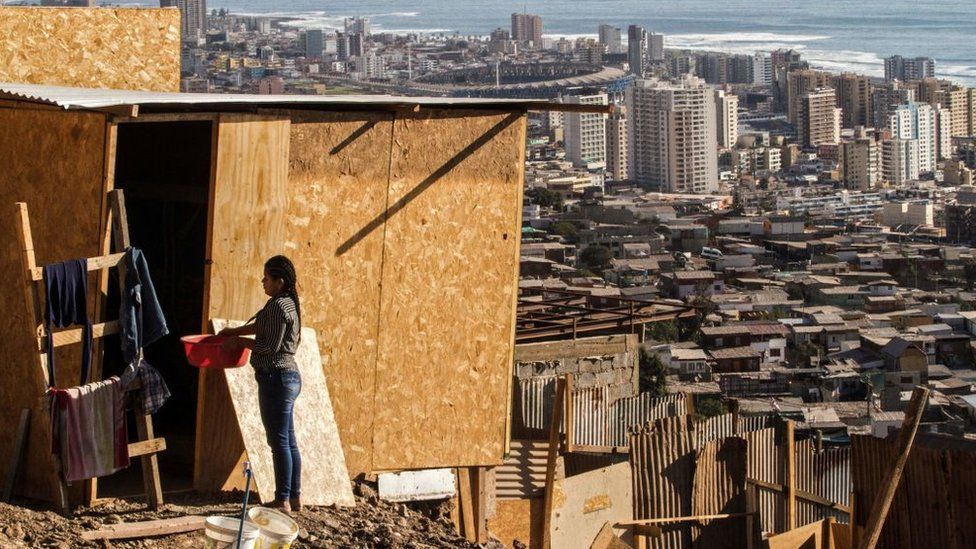

IMAGE COPYRIGHT MARCELO HERNANDEZ/GETTY image caption A new constitution was a key demand of protesters in 2019

A new constitution to replace the one dating back to Gen Pinochet’s military rule was a crucial demand of protests which swept through Chile in 2019.

Government-backed candidates have only secured about a fourth of the seats.

That is short of the number which would have made it possible for them to block sweeping changes.

Right-wing President Sebastián Piñera said it was a historic election in which citizens had sent a clear message, and that his government and other traditional parties were not attuned to the demands and aspirations of the people.

How did we get here?

Last October, an overwhelming majority of Chileans voted in favour of rewriting the constitution in a referendum, held as a result of mass street demonstrations across the country a year earlier.

Millions of Chileans are heavily indebted, for example, often to pay for schooling and private pensions.

What happens now?

The Constitutional Convention is made up of 155 citizens, and it is the first in the world to stipulate parity between male and female members. Proposals will require two-thirds approval.

With 98.3% of the votes counted, independent candidates had secured 48 seats, the left 28, the centre-left 25, and the right-wing coalition 37. Seventeen seats have been set aside for representatives of indigenous groups, who are not mentioned in the existing charter.

The government, which enjoys the support of the business community, was hoping to secure at least a third of the seats to be able to block proposals they do not agree with.

What do people want in the new text?

Poverty levels have dropped dramatically in Chile over the last 20 years, and the country is now the richest in South America on a per capita basis. But it remains one of the world’s most unequal nations.

Some of the more controversial proposals include changes to private property rights enshrined in the current text as well as to the employment legislation, which could clash with interests of traditional investors.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GLENN ARCOS/AFP

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GLENN ARCOS/AFPParties on the left want greater state control of mineral and natural resources – Chile is the world’s largest copper producer – and more public spending on education, health, pensions and social welfare.

Guillermo Guzmán, a 57-year-old architect, told AFP news agency that he voted “in the hope of getting change for the country… So that we can build a new constitution that is very different to the one left to us by the dictatorship”.

But those on the right say the free-market system in place is one of the main factors behind Chile’s economic growth.

What has the reaction been?

The president said it was “a great opportunity” for Chileans to build a more “fair, inclusive, prosperous and sustainable country”, saying: “It’s our duty to listen with humility and attention to the message of the people.”

But he also cautioned against extreme changes that some fear could threaten the country’s reputation as being one of the most stable in the region.

Gabriel Boric, a leading member of the far-left coalition, said the result paved the way for major changes. “We’re looking for a new treaty for our indigenous populations, to recover our natural resources, build a state that guarantees universal social rights.”

IMAGE COPYRIGHT MARCELO HERNANDEZ/GETTY

IMAGE COPYRIGHT MARCELO HERNANDEZ/GETTYMireya Davila, of the University of Chile’s Institute of Public Affairs, told AFP the political system was “being reconfigured”, adding: “The electoral force of the independents is much greater than previously thought and this confirms that the citizenry is fed up with the traditional parties.”

But she said the process of writing a new text would be “complex” because it would “require negotiating with each of the independents and dealing with each of their positions”.

The popularity of the Piñera government has fallen recently amid poverty and joblessness related to the Covid-19 pandemic. The country, however, has carried out one of the fastest vaccination rollouts in the world.