IMAGE COPYRIGHT ANBARASAN/BBC image caption Nawang Dorjay said he feared for his life when the simmering tension between India and China turned violent

By Ethirajan Anbarasan

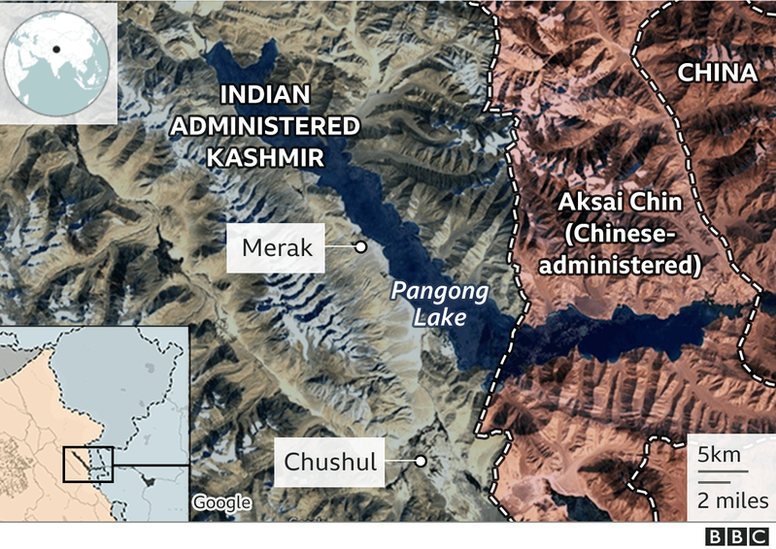

BBC News, Pangong Tso, Ladakh

The 62-year-old veteran, who runs a small convenience store in the village of Merak, feared for his life as he went along the mountain crest, carrying ammunition and other essentials. Mr Dorjay had been recruited along with hundreds of others from nearby villages when tensions escalated dramatically between the two armies last year.

“We came close to the Chinese and we thought they might target us,” he said.

A year ago, India and China accused each other of intruding into each other’s territory in Ladakh. In fact, most of the estimated 3,440km-long border has been undefined since a war in 1962, with both countries having different perceptions of their frontier.

According to Indian media, the confrontation began after Chinese forces put up tents, dug trenches and moved heavy equipment several kilometres inside what had been regarded by India as its territory.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGESVisits to the lake have been rare since – travellers were only allowed to return in January, and the BBC is one of few media outlets to reach villages like Merak, home to around 350 people, many of them nomads. Here, though, life goes on much as it did before, women in their traditional attire tend to yaks and pashmina goats, and the village seems relatively untouched by coronavirus pandemic.

There are reminders here and there of the lurking danger that overshadows the picture postcard scenery: army vehicles carry supplies and soldiers frequent the newly-laid single lane road to the fortified forward areas. For decades, the simmering tension between India and China has overshadowed this region.

“During winter, our people from here and the nearby Chushul area used to take Yaks and goats to graze in the mountains on the other side,” Mr Dorjay said. “But over the years the Chinese have gradually taken over Indian territory and the grazing areas have reduced.”

The repercussions of last year’s border scuffles are also being felt a long way from this inhospitable territory.

“The border stand-off in the past year has profoundly altered India-China bilateral relations,” said Ajai Shukla, an Indian military expert who once served as a colonel in the army. “The Chinese have put on the table an earlier claim line that the Chinese had laid out in 1959. If India were to accept that, it would lose a significant chunk of territory,” he said.

According to Mr Shukla and several other experts, China’s advance into Eastern Ladakh means hundreds of square kilometres of territory that India claimed as its own effectively became China’s.

China already controls the Aksai Chin plateau further east of Ladakh. This region, claimed by India, is strategically important for Beijing as it connects its Xinjiang province with western Tibet. Beijing has consistently argued that it was Delhi’s provocative actions in Ladakh that led to the current stand-off.

“From the Chinese point of view, Indian soldiers have been building roads and other infrastructure in Ladakh’s Galwan valley, which according to China falls under its territory,” Zhou Bo, a retired Senior Colonel in the People’s Liberation Army, told the BBC.

“From the Chinese side we insist on the traditional customary line as China-India border while India insists on the Line of Actual Control before the war in 1962,” he said. “But there is a fundamental difference over where the Line of Actual Control lies.”

IMAGE COPYRIGHT ANBARASAN/BBC

IMAGE COPYRIGHT ANBARASAN/BBCBack in the mountains, the ongoing tensions have caused problems for villagers in the Pangong Tso lake area, especially after Delhi agreed to pull back its troops from certain areas.

“The Indian army is not allowing the nomads to take their livestock to the traditional winter grazing land in the mountains,” said Konchok Stanzin, an independent councillor representing the border village of Chushul.

“When the nomads go and set up tents and pens for livestock in the mountains, that creates a landmark. During border negotiations these landmarks are important. If the nomads are stopped from going to their traditional grazing land it could be to our disadvantage in the long run,” he said.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT ANBARASAN/BBC

IMAGE COPYRIGHT ANBARASAN/BBCIn a response to Mr Stanzin, the Indian army in April said the Line of Actual Control had not been delineated, leading to “incorrect interpretation of alignment by civilians”.

It also said that because of the “present operational situation in Eastern Ladakh, the graziers have been advised to restrict their cattle movements”.

The border stand-off has faded from the media as India copes with a devastating second wave of coronavirus, but experts warn it may come back to haunt the Indian prime minister, Narendra Modi.

Mr Modi’s initial response last spring – saying there had been no intrusion – caused dismay among Indian defence experts. Things have not moved on much since then, Mr Shukla said.

“India’s political leadership is pretending that no territory has been lost to the Chinese,” he said. “The government wants to hide its failures. But if we pretend that no territory has been lost, how are we going to demand it back?”

IMAGE COPYRIGHT ANBARASAN/BBC

IMAGE COPYRIGHT ANBARASAN/BBCOn its part, Delhi realises that China is a superior military power and one of its largest trading partners. Without Chinese imports and investments, many Indian businesses will struggle.

India is now desperately importing life-saving medical equipment and medical oxygen equipment from Chinese entrepreneurs as the country reels from the pandemic.

That’s why many are urging both countries to move on from the current stand-off and maintain peace and tranquillity along the border.

“I believe this is not a watershed moment in our bilateral relationship, but it should be a turning point for us to think how we can really enhance confidence building measures,” Mr Zhou said.