IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGES

In 2016 North Korean hackers planned a $1bn raid on Bangladesh’s national bank and came within an inch of success – it was only by a fluke that all but $81m of the transfers were halted, report Geoff White and Jean H Lee. But how did one of the world’s poorest and most isolated countries train a team of elite cyber-criminals?

It all started with a malfunctioning printer. It’s just part of modern life, and so when it happened to staff at Bangladesh Bank they thought the same thing most of us do: another day, another tech headache. It didn’t seem like a big deal.

But this wasn’t just any printer, and it wasn’t just any bank.

Bangladesh Bank is the country’s central bank, responsible for overseeing the precious currency reserves of a country where millions live in poverty.

And the printer played a pivotal role. It was located inside a highly secure room on the 10th floor of the bank’s main office in Dhaka, the capital. Its job was to print out records of the multi-million-dollar transfers flowing in and out of the bank.

When staff found it wasn’t working, at 08:45 on Friday 5 February 2016, “we assumed it was a common problem just like any other day,” duty manager Zubair Bin Huda later told police. “Such glitches had happened before.”

In fact, this was the first indication that Bangladesh Bank was in a lot of trouble. Hackers had broken into its computer networks, and at that very moment were carrying out the most audacious cyber-attack ever attempted. Their goal: to steal a billion dollars.

To spirit the money away, the gang behind the heist would use fake bank accounts, charities, casinos and a wide network of accomplices.

But who were these hackers and where were they from?

According to investigators the digital fingerprints point in just one direction: to the government of North Korea.

SPOILER ALERT: This is the story told in the 10-episode BBC World Service podcast, The Lazarus Heist – click here to listen. This article is a 20-minute read.

That North Korea would be the prime suspect in a case of cyber-crime might to some be a surprise. It’s one of the world’s poorest countries, and largely disconnected from the global community – technologically, economically, and in almost every other way.

And yet, according to the FBI, the audacious Bangladesh Bank hack was the culmination of years of methodical preparation by a shadowy team of hackers and middlemen across Asia, operating with the support of the North Korean regime.

In the cyber-security industry the North Korean hackers are known as the Lazarus Group, a reference to a biblical figure who came back from the dead; experts who tackled the group’s computer viruses found they were equally resilient.

Little is known about the group, though the FBI has painted a detailed portrait of one suspect: Park Jin-hyok, who also has gone by the names Pak Jin-hek and Park Kwang-jin.

It describes him as a computer programmer who graduated from one of the country’s top universities and went to work for a North Korean company, Chosun Expo, in the Chinese port city of Dalian, creating online gaming and gambling programs for clients around the world.

While in Dalian, he set up an email address, created a CV, and used social media to build a network of contacts. Cyber-footprints put him in Dalian as early as 2002 and off and on until 2013 or 2014, when his internet activity appears to come from the North Korean capital, Pyongyang, according to an FBI investigator’s affidavit.

The agency has released a photo plucked from a 2011 email sent by a Chosun Expo manager introducing Park to an outside client. It shows a clean-cut Korean man in his late 20s or early 30s, dressed in a pin-striped black shirt and chocolate-brown suit. Nothing out of the ordinary, at first glance, apart from a drained look on his face.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGESBut the FBI says that while he worked as a programmer by day, he was a hacker by night.

In June 2018, US authorities charged Park with one count of conspiracy to commit computer fraud and abuse, and one count of conspiracy to commit wire fraud (fraud involving mail, or electronic communication) between September 2014 and August 2017. He faces up to 20 years in prison if he is ever tracked down. (He returned from China to North Korea four years before the charges were filed.)

But Park, if that is his real name, didn’t become a hacker for the state overnight. He is one of thousands of young North Koreans who have been cultivated from childhood to become cyber-warriors – talented mathematicians as young as 12 taken from their schools and sent to the capital, where they are given intensive tuition from morning till night.

When the bank’s staff rebooted the printer, they got some very worrying news. Spilling out of it were urgent messages from the Federal Reserve Bank in New York – the “Fed” – where Bangladesh keeps a US-dollar account. The Fed had received instructions, apparently from Bangladesh Bank, to drain the entire account – close to a billion dollars.

The Bangladeshis tried to contact the Fed for clarification, but thanks to the hackers’ very careful timing, they couldn’t get through.

The hack started at around 20:00 Bangladesh time on Thursday 4 February. But in New York it was Thursday morning, giving the Fed plenty of time to (unwittingly) carry out the hackers’ wishes while Bangladesh was asleep.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGESThe next day, Friday, was the start of the Bangladeshi weekend, which runs from Friday to Saturday. So the bank’s HQ in Dhaka was beginning two days off. And when the Bangladeshis began to uncover the theft on Saturday, it was already the weekend in New York.

“So you see the elegance of the attack,” says US-based cyber-security expert Rakesh Asthana. “The date of Thursday night has a very defined purpose. On Friday New York is working, and Bangladesh Bank is off. By the time Bangladesh Bank comes back on line, the Federal Reserve Bank is off. So it delayed the whole discovery by almost three days.”

And the hackers had another trick up their sleeve to buy even more time. Once they had transferred the money out of the Fed, they needed to send it somewhere. So they wired it to accounts they’d set up in Manila, the capital of the Philippines. And in 2016, Monday 8 February was the first day of the Lunar New Year, a national holiday across Asia.

By exploiting time differences between Bangladesh, New York and the Philippines, the hackers had engineered a clear five-day run to get the money away.

They had had plenty of time to plan all of this, because it turns out the Lazarus Group had been lurking inside Bangladesh Bank’s computer systems for a year.

In January 2015, an innocuous-looking email had been sent to several Bangladesh Bank employees. It came from a job seeker calling himself Rasel Ahlam. His polite enquiry included an invitation to download his CV and cover letter from a website. In reality, Rasel did not exist – he was simply a cover name being used by the Lazarus Group, according to FBI investigators. At least one person inside the bank fell for the trick, downloaded the documents, and got infected with the viruses hidden inside.

Once inside the bank’s systems, Lazarus Group began stealthily hopping from computer to computer, working their way towards the digital vaults and the billions of dollars they contained.

And then they stopped.

Why did the hackers only steal the money a whole year after the initial phishing email arrived at the bank? Why risk being discovered while hiding inside the bank’s systems all that time? Because, it seems, they needed the time to line up their escape routes for the money.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GOOGLE

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GOOGLEJupiter Street is a busy thoroughfare in Manila. Next to an eco-hotel and a dental surgery is a branch of RCBC, one of the country’s largest banks. In May 2015, a few months after the hackers accessed Bangladesh Bank’s systems, four accounts were set up here by the hackers’ accomplices. In hindsight, there were some suspicious signs: the driver’s licences used to set up the accounts were fakes, and the applicants all claimed to have exactly the same job title and salary, despite working at different companies. But no-one seemed to notice. For months the accounts sat dormant with their initial $500 deposit untouched while the hackers worked on other aspects of the plan.

By February 2016, having successfully hacked into Bangladesh Bank and created conduits for the money, the Lazarus Group was ready.

But they still had one final hurdle to clear – the printer on the 10th floor. Bangladesh Bank had created a paper back-up system to record all transfers made from its accounts. This record of transactions risked exposing the hackers’ work instantly. And so they hacked into the software controlling it and took it out of action.

With their tracks covered, at 20:36 on Thursday 4 February 2016, the hackers began making their transfers – 35 in all, totalling $951m, almost the entire contents of Bangladesh Bank’s New York Fed account. The thieves were on their way to a massive payday – but just as in a Hollywood heist movie, a single, tiny detail would catch them out.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGESAs Bangladesh Bank discovered the missing money over the course of that weekend, they struggled to work out what had happened. The bank’s governor knew Rakesh Asthana and his company, World Informatix, and called him in for help. At this point, Asthana says, the governor still thought he could claw back the stolen money. As a result, he kept the hack secret – not just from the public, but even from his own government.

Meanwhile, Asthana was discovering just how deep the hack went. He found out the thieves had gained access to a key part of Bangladesh Bank’s systems, called Swift. It’s the system used by thousands of banks around the world to co-ordinate transfers of large sums between themselves. The hackers didn’t exploit a vulnerability in Swift – they didn’t need to – so as far as Swift’s software was concerned the hackers looked like genuine bank employees.

It soon became clear to Bangladesh Bank’s officials that the transactions couldn’t just be reversed. Some money had already arrived in the Philippines, where the authorities told them they would need a court order to start the process to reclaim it. Court orders are public documents, and so when Bangladesh Bank finally filed its case in late February, the story went public and exploded worldwide.

The consequences for the bank’s governor were almost instant. “He was asked to resign,” says Asthana. “I never saw him again.”

US Congresswoman Carolyn Maloney remembers clearly where she was when she first heard about the raid on Bangladesh Bank. “I was leaving Congress and going to the airport and reading about the heist, and it was fascinating, shocking – a terrifying incident, probably one of the most terrifying that I’ve ever seen for financial markets.”

As a member of the congressional Committee on Financial Services, Maloney saw the bigger picture: with Swift underpinning so many billions of dollars of global trade, a hack like this could fatally undermine confidence in the system.

She was particularly concerned by the involvement of the Federal Reserve Bank. “They were the New York Fed, which usually is so careful. How in the world did these transfers happen?”

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGESMaloney contacted the Fed, and staff explained to her that most of the transfers had in fact been prevented – thanks to a tiny, coincidental detail.

The RCBC bank branch in Manila to which the hackers tried to transfer $951m was in Jupiter Street. There are hundreds of banks in Manila that the hackers could have used, but they chose this one – and the decision cost them hundreds of millions of dollars.

“The transactions… were held up at the Fed because the address used in one of the orders included the word ‘Jupiter’, which is also the name of a sanctioned Iranian shipping vessel,” says Carolyn Maloney.

Just the mention of the word “Jupiter” was enough to set alarm bells ringing in the Fed’s automated computer systems. The payments were reviewed, and most were stopped. But not all. Five transactions, worth $101m, crossed this hurdle.

Of that, $20m was transferred to a Sri Lankan charity called the Shalika Foundation, which had been lined up by the hackers’ accomplices as one conduit for the stolen money. (Its founder, Shalika Perera, says she believed the money was a legitimate donation.) But here again, a tiny detail derailed the hackers’ plans. The transfer was made to the “Shalika Fundation”. An eagle-eyed bank employee spotted the spelling mistake and the transaction was reversed.

And so $81m got through. Not what the hackers were aiming for, but the lost money was still a huge blow for Bangladesh, a country where one in five people lives below the poverty line.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGESBy the time Bangladesh Bank began its efforts to claw the money back, the hackers had already taken steps to make sure it stayed beyond reach.

On Friday 5 February, the four accounts set up the previous year at the RCBC branch in Jupiter Street suddenly sprang to life.

The money was transferred between accounts, sent to a currency exchange firm, swapped into local currency and re-deposited at the bank. Some of it was withdrawn in cash. For experts in money laundering, this behaviour makes perfect sense.

“You have to make all of that criminally derived money look clean and look like it has been derived from legitimate sources in order to protect whatever you do with the money afterwards,” says Moyara Ruehsen, director of the Financial Crime Management Programme at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies in Monterey, California. “You want to make the money trail as muddy and obscure as possible.”

Even so, it was still possible for investigators to trace the path of the money. To make it completely untrackable it had to leave the banking system.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGESThe Solaire sits on the waterfront in Manila, a gleaming white palace of hedonism, home to a hotel, a huge theatre, high-end shops and – its most famous attraction – a sprawling casino floor. Manila has become a big draw for gamblers from mainland China, where the pastime is illegal, and the Solaire is “one of the most elegant casino floors in Asia”, according to Mohammed Cohen, editor-at-large of Inside Asian Gaming Magazine. “It’s really beautifully designed, comparable to anything in south-east Asia. It has roughly 400 gaming tables and about 2,000 slot machines.”

It was here in Manila’s glitzy casino scene that the Bangladesh Bank thieves mounted the next stage of their money laundering operation. Of the $81m that washed through the RCBC bank, $50m was deposited in accounts at the Solaire and another casino, the Midas. (What happened to the other $31m? According to a Philippines Senate Committee set up to investigate, it was paid to a Chinese man called Xu Weikang, who’s believed to have left town on a private jet and never been heard of since.)

The idea of using casinos was to break the chain of traceability. Once the stolen money had been converted into casino chips, gambled over the tables, and changed back into cash, it would be almost impossible for investigators to trace it.

But what about the risks? Aren’t the thieves in danger of losing the loot across the casino tables? Not at all.

Firstly, instead of playing in the public parts of the casino, the thieves booked private rooms and filled them with accomplices who would play at the tables; this gave them control over how the money was gambled. Secondly, they used the stolen money to play Baccarat – a wildly popular game in Asia, but also a very simple one. There are only three outcomes on which to bet, and a relatively experienced player can recoup 90% or more of their stake (an excellent outcome for money launderers, who often get a far smaller return). The criminals could now launder the stolen funds and look forward to a healthy return – but to do so would take careful management of the players and their bets, and that took time. For weeks, the gamblers sat inside Manila’s casinos, washing the money.

Bangladesh Bank, meanwhile, was catching up. Its officials had visited Manila and identified the money trail. But when it came to the casinos, they hit a brick wall. At that time, the Philippines gambling houses were not covered by money laundering regulations. So far as the casinos were concerned, the cash had been deposited by legitimate gamblers, who had every right to fritter it away over the tables. (The Solaire casino says it had no idea it was dealing with stolen funds, and is co-operating with the authorities. The Midas did not respond to requests for comment.)

The bank’s officials managed to recover $16m of the stolen money from one of the men who organised the gambling jaunts at the Midas casino, called Kim Wong. He was charged, but the charges were later dropped. The rest of the money, however – $34m – was leaching away. Its next stop, according to investigators, would take it one step closer to North Korea.

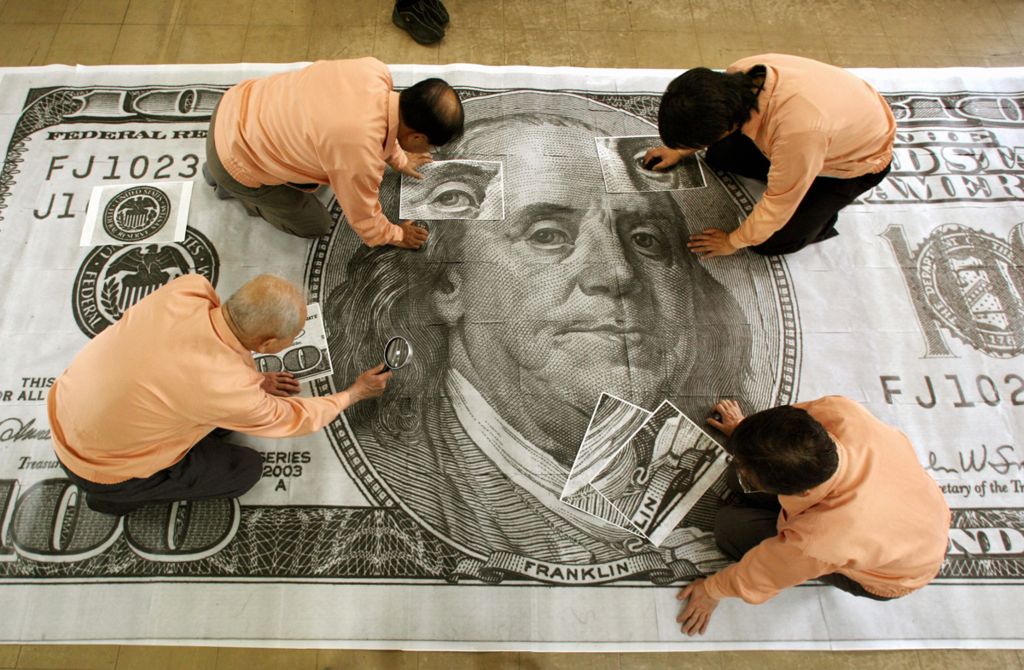

Macau is an enclave of China, similar in constitution to Hong Kong. Like the Philippines, it’s a hotspot for gambling and home to some of the world’s most prestigious casinos. The country also has long-established links to North Korea. It was here that North Korean officials were in the early 2000s caught laundering counterfeit $100 notes of extremely high quality – so-called “Superdollars” – which US authorities claim were printed in North Korea. The local bank they laundered them through was eventually placed on a US sanctions list thanks to its connections with the Pyongyang regime.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT EMPICS

IMAGE COPYRIGHT EMPICSIt was also in Macau that a North Korean spy was trained before she bombed a Korean Air flight in 1987, killing 115 people. And it was in Macau that Kim Jong-un’s half brother, Kim Jong-nam, lived in exile before being fatally poisoned in Malaysia in an assassination many believe was authorised personally by the North Korean leader.

As the money stolen from Bangladesh Bank was laundered through the Philippines, numerous links to Macau started to emerge. Several of the men who organised the gambling jaunts in the Solaire were traced back to Macau. Two of the companies that had booked the private gambling rooms were also based in Macau. Investigators believe most of the stolen money ended up in this tiny Chinese territory, before being sent back to North Korea.

At night, North Korea famously appears to be a black hole in photos taken from outer space by Nasa, due to the lack of electricity in most parts of the country – in stark contrast to South Korea, which explodes with light at all hours of the day and night. North Korea ranks among the 12 poorest nations in the world, with an estimated GDP of just $1,700 per person – less than Sierra Leone and Afghanistan, according to the CIA.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT NASA

IMAGE COPYRIGHT NASAAnd yet North Korea has produced some of the world’s most brazen and sophisticated hackers, it appears.

Understanding how, and why, North Korea has managed to cultivate elite cyber-warfare units requires looking at the family that has ruled North Korea since its inception as a modern nation in 1948: the Kims.

Founder Kim Il-sung built the nation officially known as the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea on a political system that is socialist but operates more like a monarchy.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGESHis son, Kim Jong-il, relied on the military as his power base, provoking the US with tests of ballistic missile and nuclear devices. In order to fund the programme, the regime turned to illicit methods, according to US authorities – including the highly sophisticated counterfeit Superdollars.

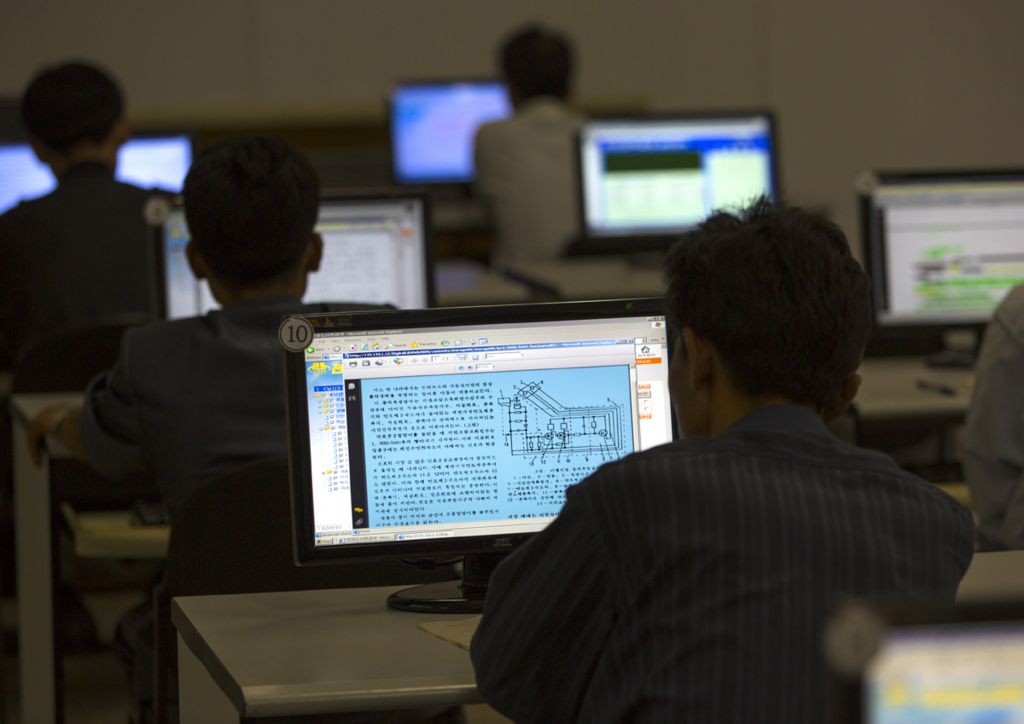

Kim Jong-il also decided early on to incorporate cyber into the country’s strategy, establishing the Korea Computer Centre in 1990. It remains the heart of the country’s IT operations.

When, in 2010, Kim Jong-un – Kim Jong-il’s third son – was revealed as his heir apparent, the regime unfurled a campaign to portray the future leader, only in his mid-20s and unknown to his people, as a champion of science and technology. It was a campaign designed to secure his generation’s loyalty and to inspire them to become his warriors, using these new tools.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGESThe young Kim, who took power in late 2011 upon his father’s death, called nuclear weapons a “treasured sword”, but he too needed a way to fund them – a task complicated by the ever tighter sanctions imposed by the UN Security Council after the country’s first tests of a nuclear device and a long-range ballistic missile in 2006. Hacking was one solution, US authorities say.

The embrace of science and technology did not extend to allowing North Koreans to freely connect to the global internet, though – that would enable too many to see what the world looks like outside their borders, and to read accounts that contradict the official mythology.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGESSo in order to train its cyber-warriors, the regime sends the most talented computer programmers abroad, mostly to China.

There they learn how the rest of the world uses computers and the internet: to shop, to gamble, to network and to be entertained. It’s there, experts say, that they are transformed from mathematical geniuses into hackers.

Scores of these young men are believed to live and work in North Korean-run outposts in China.

“They are very good at masking their tracks but sometimes, just like any other criminal, they leave crumbs, evidence behind,” says Kyung-jin Kim, a former FBI Korea chief now who now works as a private sector investigator in Seoul. “And we’re able to identify their IP addresses back to their location.”

Those crumbs led investigators to an unassuming hotel in Shenyang, in China’s north-east, guarded by a pair of stone tigers, a traditional Korean motif. The hotel was called the Chilbosan, after a famous mountain range in North Korea.

Photos posted to hotel review sites such as Agoda reveal charming Korean touches: colourful bedspreads, North Korean cuisine and waitresses who sing and dance for their customers.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGESIt was “well-known in the intel community”, says Kyung-jin Kim, that suspected North Korean hackers were operating from the Chilbosan when they first broke on to the world stage in 2014.

Meanwhile, in the Chinese city of Dalian, where Park Jin-hyok is believed to have lived for a decade, a community of computer programmers was living and working in a similar North-Korea-run operation, says defector Hyun-seung Lee.

Lee was born and raised in Pyongyang but lived for years in Dalian, where his father was a well-connected businessman working for the North Korean government – until the family defected in 2014. The bustling port city across the Yellow Sea from North Korea was home to about 500 North Koreans when he was living there, Lee says.

Among them, more than 60 were programmers – young men he got to know, he says, when North Koreans gathered for national holidays, such as Kim Il-sung’s birthday.

One of them invited him over to their living quarters. There, Lee saw “about 20 people living together and in one space. So, four-to-six people living in one room, and then the living room they made it like an office – all the computers, all in the living room.”

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGESThey showed him what they were producing: mobile phone games that they were selling to South Korea and Japan through brokers, making $1m per year.

Although North Korean security officials kept a close eye on them, life for these young men was still relatively free.

“It’s still restricted, but compared to North Korea, they have much freedom so that they can access the internet and then they can watch some movies,” Lee says.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGESAfter about eight years in Dalian, Park Jin-hyok appears to have been anxious to return to Pyongyang. In a 2011 email intercepted by the FBI, he mentions wanting to marry his fiancee. But it would be a few more years before he was allowed to do this.

The FBI says his superiors had another mission for him: a cyber-attack on one of the world’s largest entertainment companies – Sony Pictures Entertainment in Los Angeles, California. Hollywood.

In 2013, Sony Pictures announced the making of a new movie starring Seth Rogen and James Franco that would be set in North Korea.

It’s about a talk show host, played by Franco, and his producer, played by Rogen. They go to North Korea to interview Kim Jong-un, and are persuaded by the CIA to assassinate him.

North Korea threatened retaliatory action against the US if Sony Pictures Entertainment released the film, and in November 2014 an email was sent to company bosses from hackers calling themselves the Guardians of Peace, threatening to do “great damage”.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGESThree days later a horror-film image of a blood-red skeleton with fangs and glaring eyes appeared on employees’ computer screens. The hackers had made good on their threats. Executives’ salaries, confidential internal emails, and details of as-yet unreleased films were leaked online – and the company’s activities ground to a halt as its computers were disabled by the hackers’ viruses. Staff couldn’t swipe passes to enter their offices or use printers. For a full six weeks a coffee shop on the MGM lot, the HQ of Sony Pictures Entertainment, was unable to take credit cards.

Sony had initially pressed ahead with plans to release The Interview in the usual way, but these were hastily cancelled when the hackers threatened physical violence. Mainstream cinema chains said they wouldn’t show the film, so it was released only digitally and in some independent cinemas.

But the Sony attack, it turns out, may have been a dry run for an even more ambitious hack – the 2016 bank heist in Bangladesh.

Bangladesh is still trying to recover the rest of its stolen money – around $65m. Its national bank is taking legal action against dozens of people and institutions, including RCBC bank, which denies breaching any rules.

As skilful as the hacking of Bangladesh Bank was, just how pleased would the Pyongyang regime have been with the end result? After all, the plot started out as a billion-dollar heist, and the eventual haul would have been only in the tens of millions. Hundreds of millions of dollars had been lost as the thieves had navigated the global banking system, and tens of millions more as they paid off middlemen. In future, according to US authorities, North Korea would find a way to avoid this attrition.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGESIn May 2017, the WannaCry ransomware outbreak spread like wildfire, scrambling victims’ files and charging them a ransom of several hundred dollars to retrieve their data, paid using the virtual currency Bitcoin. In the UK, the National Health Service was particularly badly hit; accident and emergency departments were affected, and urgent cancer appointments had to be rescheduled.

As investigators from the UK’s National Crime Agency delved into the code, working with the FBI, they found striking similarities with the viruses used to hack into Bangladesh Bank and Sony Pictures Entertainment, and the FBI eventually added this attack to the charges against Park Jin-hyok. If the FBI’s allegations are correct, it shows North Korea’s cyber army had now embraced cryptocurrency – a vital leap forward because this high-tech new form of money largely bypasses the traditional banking system – and could therefore avoid costly overheads, such as pay-offs to middlemen.

WannaCry was just the start. In the ensuing years, tech security firms have attributed many more cryptocurrency attacks to North Korea. They claim the country’s hackers have targeted exchanges where cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin are swapped for traditional currencies. Added together, some estimates put the thefts from these exchanges at more than $2bn.

And the allegations keep coming. In February the US Department of Justice charged two other North Koreans, whom they claim are also members of the Lazarus Group and are linked to a money-laundering network stretching from Canada to Nigeria.

Find out more

Computer hacking, global money laundering, cutting edge cryptocurrency thefts… If the allegations against North Korea are true, then it appears many people have underestimated the country’s technical skill and the danger it presents.

But this also paints a disturbing picture of the dynamics of power in our increasingly connected world, and our vulnerability to what security experts call “asymmetric threat” – the ability of a smaller adversary to exercise power in novel ways that make it a far bigger threat than its size would indicate.

Investigators have uncovered how a tiny, desperately poor nation can silently reach into the email inboxes and bank accounts of the rich and powerful thousands of miles away. They can exploit that access to wreak havoc on their victims’ economic and professional lives, and drag their reputations through the mud. This is the new front line in a global battleground: a murky nexus of crime, espionage and nation-state power-mongering. And it’s growing fast.

Geoff White is the author of Crime Dot Com: From Viruses to Vote Rigging, How Hacking Went Global. Jean H Lee opened Associated Press’s Pyongyang bureau in 2012; she is now a senior fellow at the Wilson Center in Washington DC.

You may also be interested in:

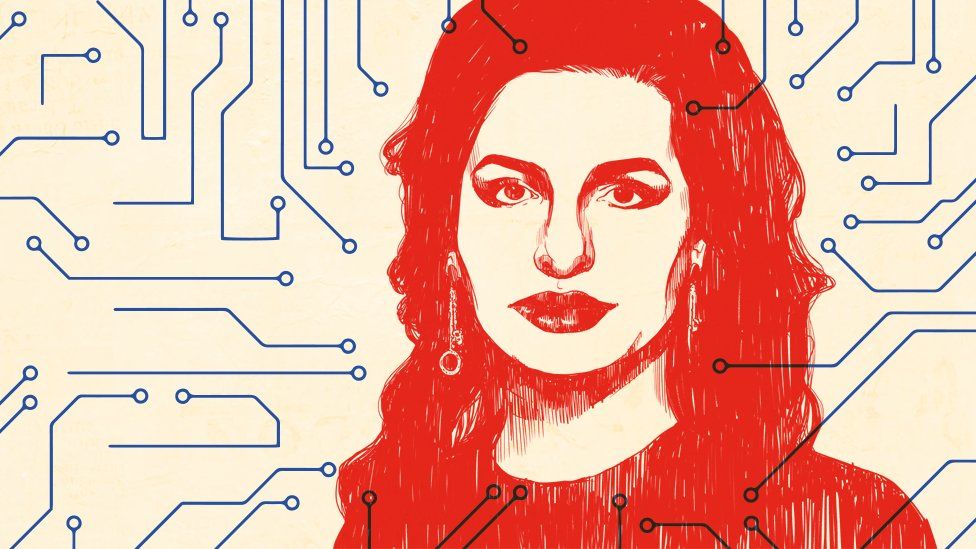

Ruja Ignatova called herself the Cryptoqueen. She told people she had invented a cryptocurrency to rival Bitcoin, and persuaded them to invest billions. Then, in 2017, she disappeared. Jamie Bartlett spent months investigating how she did it, and trying to figure out where she’s hiding.