GETTY IMAGES image captionCitizens of the city of Kolkata being vaccinated

By Shruti Menon

BBC Reality Check

India has launched a new vaccine policy which will see the federal government buying Covid-19 jabs from manufacturers and supplying to states.

India is one of the largest vaccine makers in the world but its own vaccination drive has been moving at a slow pace. It has fully vaccinated just a little over 5% of the total eligible population so far. Shortages continue to persist in many states.

To scale up the vaccination drive, Prime Minister Narendra Modi had announced earlier this month that everyone would get “free vaccines” from 21 June.

While the new policy does change the way states were procuring vaccines, it does not change much for the citizens.

“The vaccines were free for citizens [at government centres earlier also],” says Dr Chandrakant Lahariya, public policy and health systems expert.

How has the policy changed?

Prime Minister Modi’s announcement came in a national address on TV, in which he talked about the history and logistics of vaccine programmes in India.

Responsibility for vaccinations in India was being shared between the federal government in Delhi and state governments.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT REUTERS

IMAGE COPYRIGHT REUTERSUnder the earlier Covid vaccine policy, half of all vaccines produced in India went to the federal government, and the rest went to state administrations and private hospitals.

Although the states competed at the open market for the vaccines doses for 18-44 age group, the citizens were getting them for free at state government’s vaccination centres.

Meanwhile, the federal government was vaccinating frontline workers and those aged above 45 years- also for free.

But now the federal government will buy 75% of all vaccines manufactured.

The state governments will receive their vaccines doses for free from the federal government, instead of negotiating directly with manufacturers.

These vaccinations are not free – people have to pay at private hospitals.

The federal government has fixed prices for the three approved vaccines at 780 rupees ($10.7; £7.5) for Covishield, 1,145 rupees ($15.7; £11) for Sputnik V, and 1,410 rupees ($19.3; £13.6) for Covaxin.

What does it mean in practice?

It means that state governments will now receive their allocated vaccine doses from the federal government based on the population of those states, the level of disease, vaccination progress and vaccine wastage.

That relieves the state authorities of having to purchase doses from the manufacturer at higher prices than were offered to the federal government.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGESIt also hands more control over the vaccine rollout to the federal government.

It questioned the rationale behind making states pay more for vaccines than the federal government had to.

States had to procure them on the open market, and so the financial burden on some of the poorest states such as Bihar, Jharkhand and Uttar Pradesh significantly increased.

“This is a step in the right direction and will streamline some procurement-related challenges,” says Dr Lahariya.

What does it mean for ordinary people?

“This announcement doesn’t change much for citizens,” says Dr Lahariya.

The new policy is in fact similar to what India did when it began its vaccine rollout in January this year.

This was even acknowledged by Mr Modi himself, who said “the old system, in place before 1 May, will be implemented again.”

The original policy was changed in April, when India was hit by a dramatic surge in case numbers and India’s vaccine drive was faltering.

States were then allowed to bid for vaccines directly from manufacturers, which it was hoped would encourage other vaccine makers to enter the Indian market and boost supply.

But it didn’t work out like that, and shortages of vaccines began to emerge in a number of places as supply couldn’t keep up with demand.

We’ve looked in other pieces at the challenges that face Indian vaccine manufacturers in trying to ramp up production.

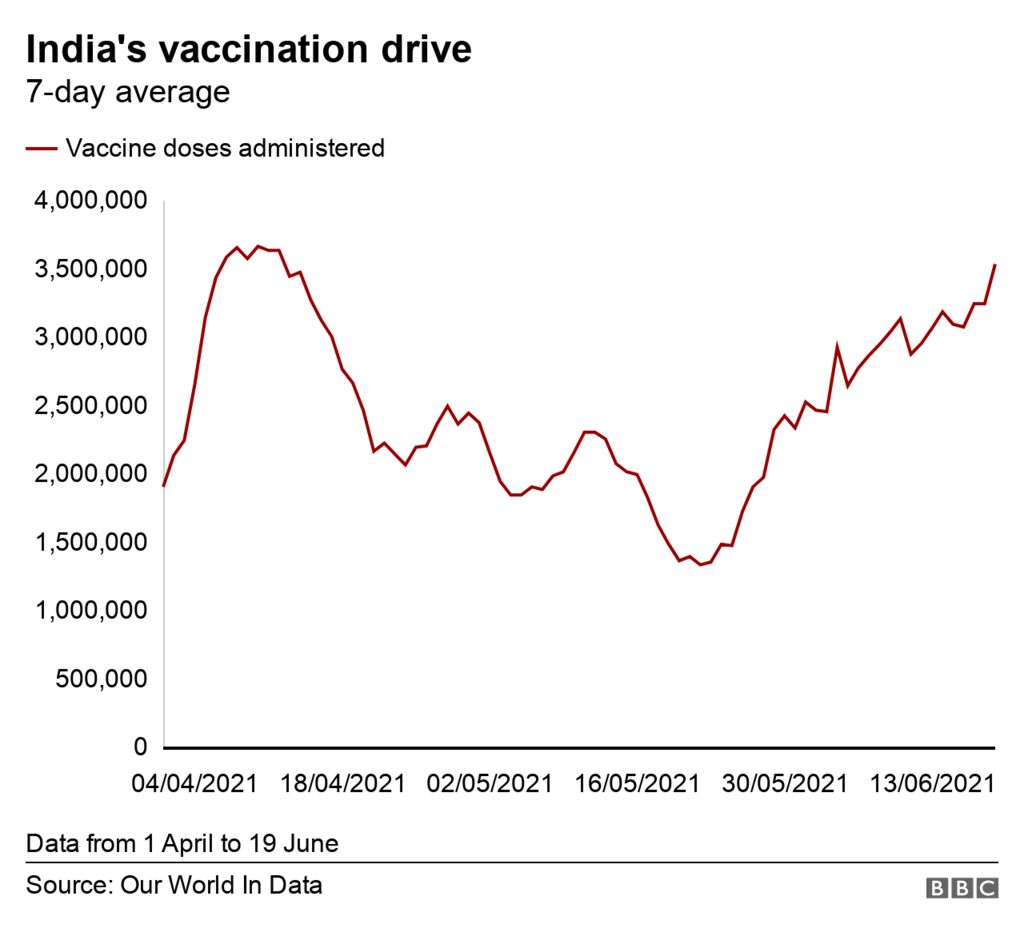

How is the vaccination drive going?

India has administered over 276 million vaccine doses since January, that’s less than 30% of the eligible adult population.

India’s adult population is estimated as being around 950 million.

The vaccine drive picked up pace in early April, with 3.66 million doses administered on 10 April, the highest so far.

But that figure then fell by nearly half in mid-May and several states suspended vaccinations for the 18-44 age group due to shortages. Experts say that India failed to order enough vaccines last year to avoid shortages.

The Indian government has pledged to vaccinate all adults by the end of the year, a target many experts say will be difficult to meet at the current pace.