GETTY IMAGES Indian Economy Modi

By Nikhil Inamdar and Aparna Alluri

BBC News, Delhi

Narendra Modi stormed India’s political stage with grand promises – of more jobs, prosperity and less red tape.

His thumping mandate – in 2014 and again in 2019 – raised hopes of big bang reforms.

But his economic record, in the seven years he’s been prime minister, has proved lacklustre. And the pandemic battered what was an already under-par performance.

Here’s how Asia’s third-largest economy has fared under Mr Modi, in seven charts.

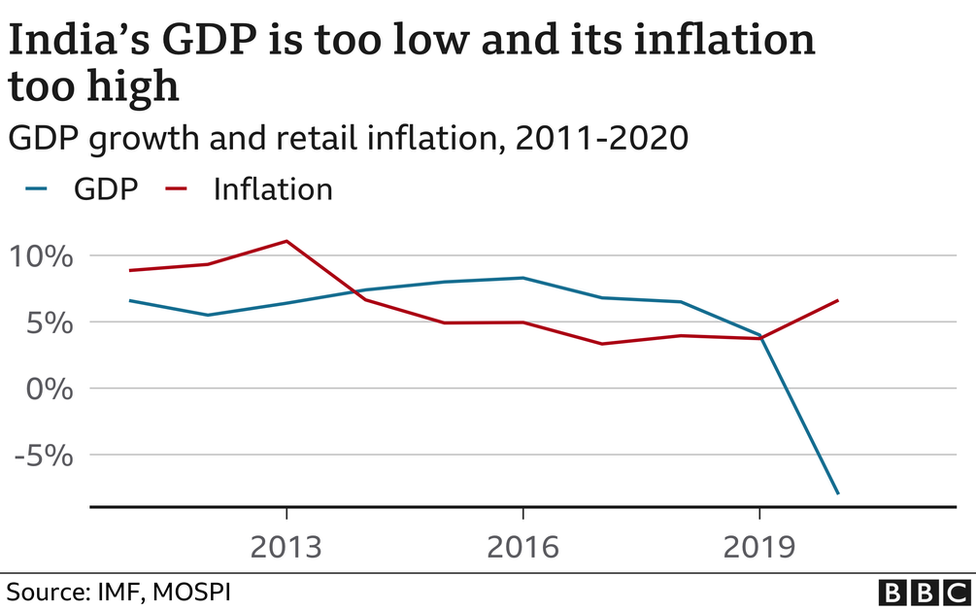

Growth is sluggish

Mr Modi’s avowed GDP target – a $5 trillion (£3.6 trillion) economy by 2025, or roughly $3 trillion after adjusting for inflation – is a pipe dream now.

Independent pre-Covid estimates for 2025 had touched $2.6 trillion at best. The pandemic has shaved off another $200-300bn.

Rising inflation, driven by global oil prices, is also a big concern, economist Ajit Ranade said.

But Covid is not solely responsible.

India’s GDP – at a high of 7-8% when Mr Modi took office – had fallen to its lowest in a decade – 3.1% – by the fourth quarter of 2019-20.

This spurred the next big problem.

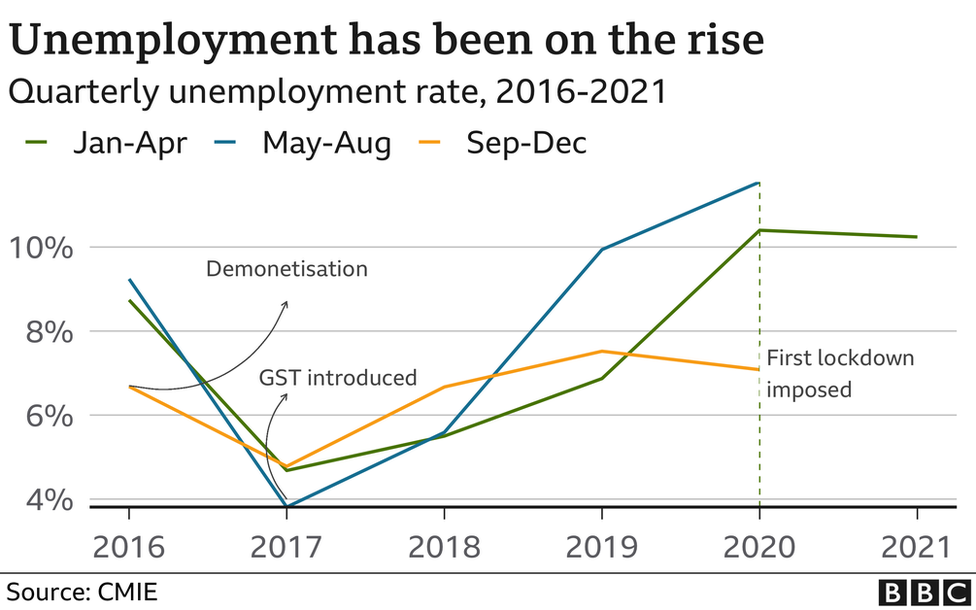

Joblessness is on the rise

“India’s biggest challenge has been a slowdown in investments since 2011-12,” said Mahesh Vyas, CEO of the Centre for Monitoring the Indian Economy (CMIE). “Then, since 2016, we have suffered too many economic shocks in quick succession.”

Unemployment climbed to a 45-year high – 6.1% – in 2017-18, according to the last official count. And it has nearly doubled since then, according to household surveys by CMIE, a widely-used proxy for labour market data.

More than 25 million people have lost their jobs since the start of 2021. And more than 75 million Indians have plunged back into poverty, including a third of India’s 100 million-strong middle class, setting back half a decade of gains, according to estimates by Pew Research.

Mr Modi’s government has also created far short of the 20 million jobs the economy needs every year, Mr Ranade said. India has been adding only around 4.3 million jobs a year for the last decade.

India is not making or exporting enough

‘Make in India’ – Mr Modi’s high-octane flagship initiative – was supposed to turn India into a global manufacturing powerhouse by cutting red tape and drawing investment for export hubs.

The goal: manufacturing would account for 25% of GDP. Seven years on, it’s share is stagnant at 15%. Worse, manufacturing jobs went down by half in the last five years, according to the Centre for Economic Data and Analysis.

Under Mr Modi, India has steadily lost market share to smaller rivals such as Bangladesh, whose remarkable growth has hinged on exports, largely fuelled by the labour-intensive garments industry.

Mr Modi has also hiked tariffs and turned increasingly protectionist in recent years – in tandem with his rallying cry for “self-reliance”.

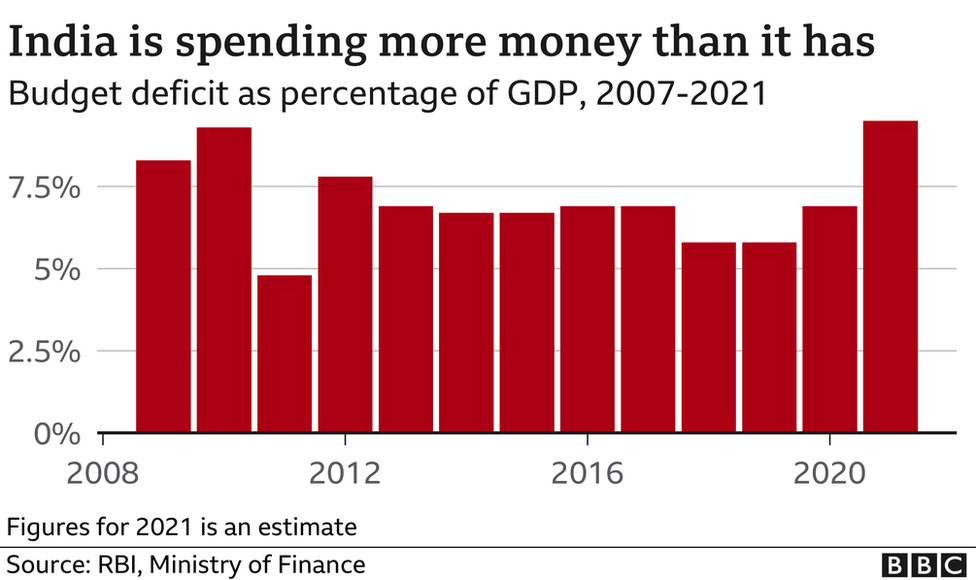

Infrastructure building is a rare bright spot

Mr Modi’s government has been laying 36km (22 miles) of highways a day on average, compared to his predecessor’s daily count of 8-11km, said Vinayak Chatterjee, co-founder of infrastructure firm Feedback Infra.

Installed renewables capacity – solar and wind – has doubled in five years. Currently at about 100 gigawatts, India is on track to achieve its 2023 target of 175 gigawatts.

Economists also largely welcomed Mr Modi’s populist signature schemes – millions of new toilets to reduce open defecation, housing loans, subsidised cooking gas and piped water for the poor.

But many of the toilets aren’t used or have no running water, and rising fuel prices have undone the benefit of the subsidy.

And the increased spending with no matching income from taxes or exports has economists worrying about India’s ballooning fiscal deficit.

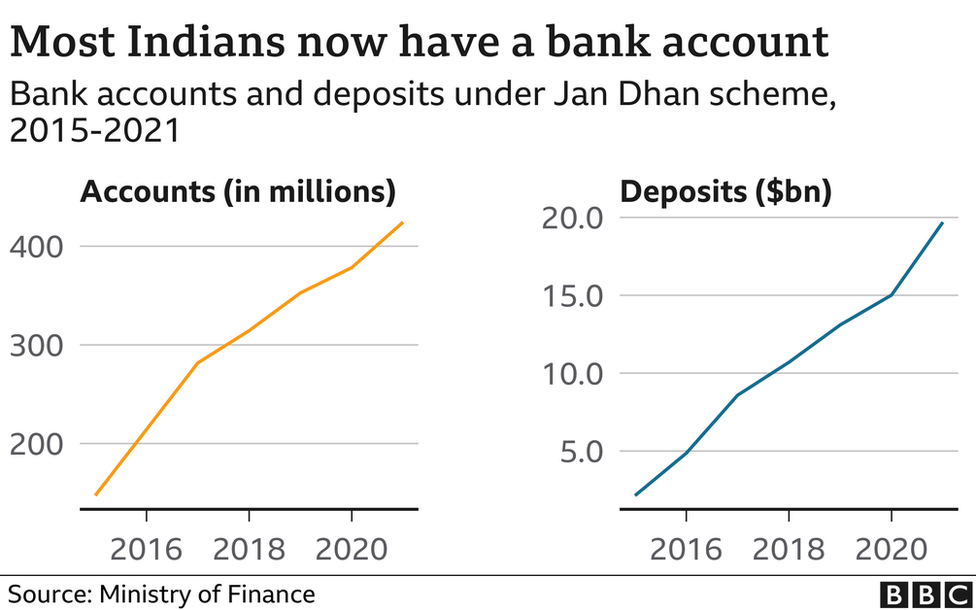

More people have joined the formal economy

This is Mr Modi’s other big achievement.

India has leapfrogged towards becoming a global leader in digital payments, thanks to a government-backed payment system. Mr Modi’s Jan Dhan scheme has enabled millions of unbanked poor families to enter the formal economy with “no-frills” bank accounts.

Accounts and deposits have risen – a good sign, although reports suggest many of these accounts lie unused.

But economists say this is a huge step in the right direction, especially since it allows the direct transfer of cash benefits, cutting out middlemen.

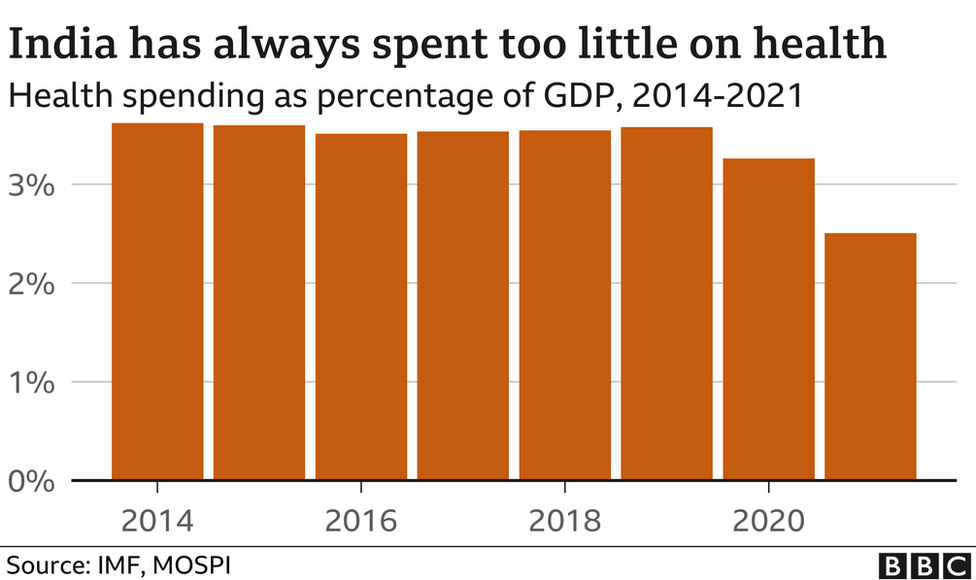

Healthcare spending is dismal

“Like previous governments, this one has continued to neglect healthcare. India has among the lowest levels of public spending on healthcare in the world,” economist Reetika Khera said.

Experts say the emphasis is on tertiary care at the expense of preventive or primary care.

“This is hurtling us towards a US-style health system which is expensive and has poorer health outcomes in spite of that,” Ms Khera added.

And Mr Modi’s ambitious health insurance scheme, launched in 2018, appears to have been under-used even during Covid.

“It was long awaited but more resources need to go into it,” said public health expert Dr Srinath Reddy. India needs to use Covid as a wake-up call to invest heavily in strengthening primary healthcare, he added.

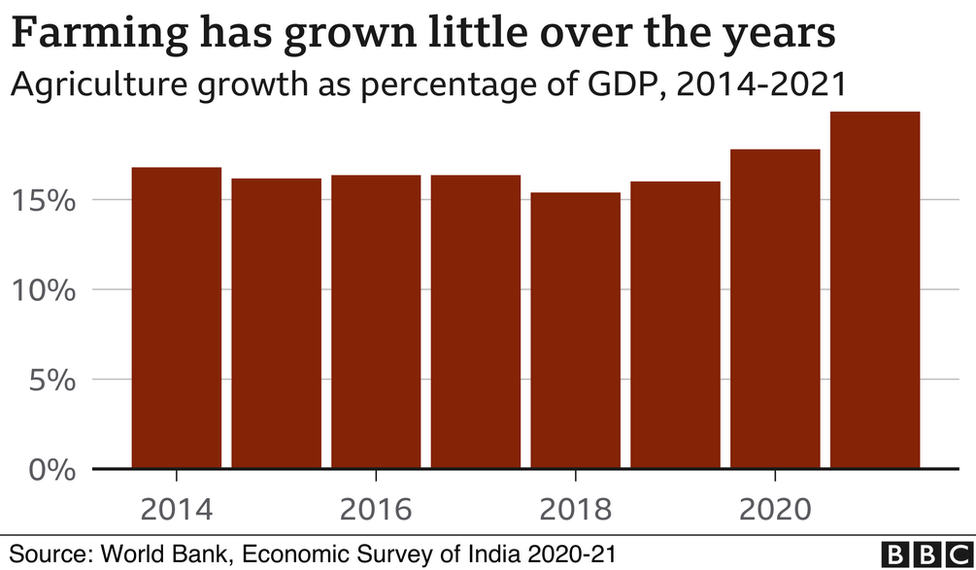

Too many still work in farming

Farming employs more than half of India’s working-age population but contributes too little to GDP.

Almost everyone agrees India’s farming sector needs reform. Pro-market laws passed last year are stuck after months-long protests by angry farmers who say they will shrink their incomes further.

Mr Modi, who had promised to double farm incomes, insists that’s not true.

But experts say piecemeal reforms will achieve little – the government instead needs to spend to make farming more affordable and profitable, economist Professor R Ramakumar said.

“Demonetisation destroyed the supply chains, some irreparably, and GST led to a rise in input prices in 2017. The government has also done very little to alleviate the pain of 2020 [Covid lockdowns],” he added.

Mr Ranade said the solution partly lies outside farming: “Agriculture will do well when other sectors are able to absorb the surplus labour.”

But that will only happen when India sees a revival in private investment – now at a 16-year low, according to CMIE – and possibly the biggest economic challenge Mr Modi faces.

Data by Kieran Lobo and charts by Shadab Nazmi