IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGES image caption Jehan Sadat was a devoted activist for women’s rights and peace around the world

By Sarah Fowler

BBC News

Her life partner, Anwar – then president of Egypt – was hit by several bullets and died two hours later in hospital. It was 6 October 1981, and Jehan’s decade-long spell as Egypt’s first lady came to an abrupt halt.

Jehan, who has died at the age of 88, spent most of her life dedicated to promoting social justice and female empowerment in Egypt, and continued to do so decades after her husband’s very public assassination.

“She led change and inspired generations to come,” says Noha Bakr, a political studies affiliate professor at the American University of Cairo.

A tough proposal

Born in Cairo in 1933 to an Egyptian father and British mother, Jehan experienced a diverse upbringing, celebrating Christmas and eating cornflakes for breakfast instead of the usual Egyptian fare of fava beans, as well as devotedly fasting each year during the Muslim festival of Ramadan.

Her dislike for gender inequality stemmed from her school days when she was advised by her parents to focus on subjects such as sewing and cooking, in preparation for marriage, as opposed to the maths and sciences that could have led to a university career.

She first met her future husband Anwar, a former army officer, at the age of 15 on a visit to her cousin’s house – not long after he was released from prison for fighting against British control in Egypt.

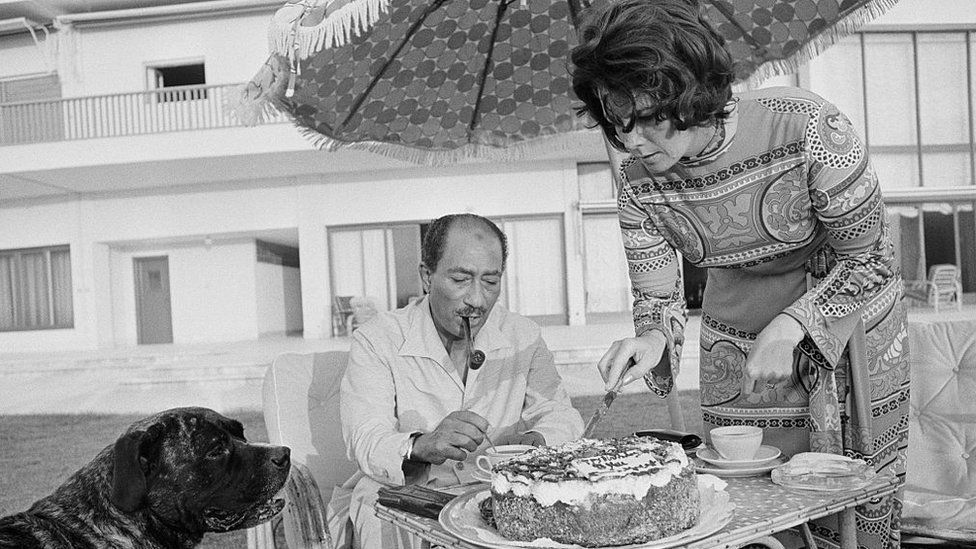

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGESHer mother in particular was reluctant to allow the marriage of her daughter to a divorced revolutionary nearly twice her age, but he won her over in a conversation about Charles Dickens. “He is intelligent. He has character. He will take good care of you. And you will never be bored,” her mother told her.

They wed in 1949 and enjoyed a marriage lasting more than three decades, having four children together.

First lady in the spotlight

Just three years later, her husband became a household name after joining a coup led by Gamel Abdel Nasser that ousted the British-backed king in Egypt from power, and changed the course of Egyptian politics forever.

Anwar Sadat went on to take several high-level posts, culminating in his election as president, after Nasser’s death in 1970.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGESJehan’s first foray into public service began in the late 1960s, when she was inspired to help several women she had met in a rural village called Talla in the Nile Delta region, who were desperate for money.

She set up a co-operative that enabled them to become skilled in sewing and economically independent from their husbands.

What started out as 25 sewing machines in an abandoned building turned into a much larger scale production line, with over 100 women making 4,000 uniforms a day for factory workers.

“She microfinanced small projects and economically empowered women – she would make exhibitions to show their work and sell them. She realised that if women are economically empowered, then they will also be politically empowered,” says Dr Bakr.

The Talla Society was the start of several projects Jehan led – she went on to form a rehabilitation programme designed for disabled army veterans and civilians and set up orphaned children’s projects in a number of cities.

Jehan’s laws

A decade later, Jehan helped lead a campaign to reform Egypt’s status law which would go on to grant women new rights to divorce their husbands and retain custody of their children.

In her book, she recounted the difficulties of convincing Anwar to back the reforms. “Over half our population are women, Anwar. Egypt will not be a democracy until women are as free as men,” she told him. “As leader of our country, it is your duty to make that happen.”

Despite a backlash from conservative Muslims, in the summer of 1979 President Sadat granted her wish and issued decrees improving the divorce status of women, as well as a second law that set aside 30 seats in parliament for women. These measures, which were later passed through parliament, became known as ‘Jehan’s laws’.

“Her actions and her work changed the world’s views on Arab women and it paved the way for future First Ladies to play a more active role in politics,” says Mervat Kojok, who knew Jehan personally as head of the Egyptian diplomat wives association.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGESAt the age of 41, Jehan decided to return to school and enrolled at Cairo University to study Arabic Literature – attending university at the same time as three of her grown up children.

She would go on to earn a masters and doctorate degree in Comparative Literature and in her later years, took on lecturing posts in Cairo and the US.

Noha Bakr recalls watching Jehan Sadat defend her thesis live on a black and white TV, and said many women – including herself – saw this as an example to follow.

“In my late 30s, I returned to university to continue my PhD after having kids. Who inspired me? She did.”

Widow at 46

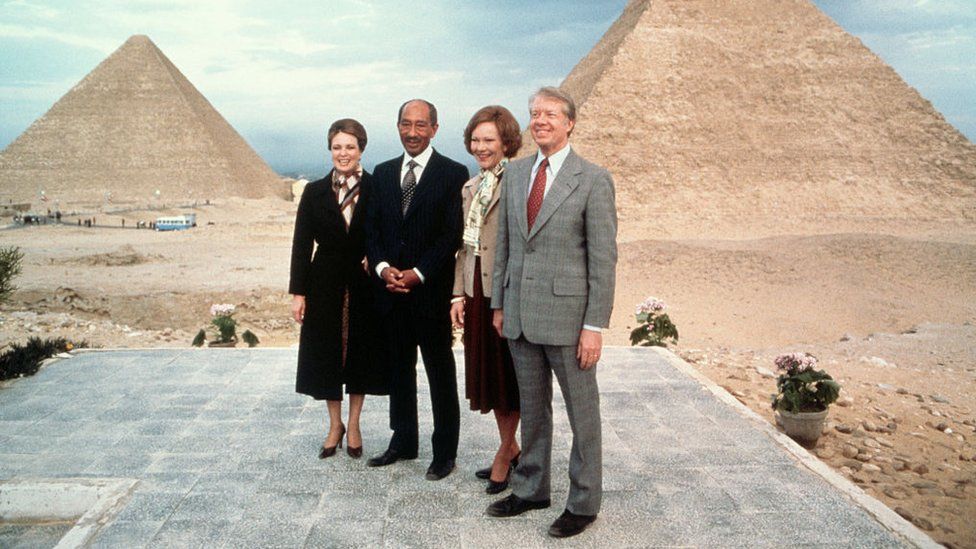

In 1978, Anwar Sadat became the first Arab leader to make peace with Israel after a series of diplomatic efforts brokered by then-US President Jimmy Carter. The same year he and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin were jointly awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGESThe decision angered many Egyptians and led to violent demonstrations against him. Even Jehan admitted she was taken aback by the move at first, but would go on to support his plan.

“His peace idea came as a shock, and not just to me, but the whole Arab world,” she once told the Jewish Chronicle.

Two years after signing the historic treaty that was hailed internationally but condemned by many of his allies in the Arab world, Anwar was gunned down by a group of Islamist extremists at that military event in Cairo commemorating Egypt’s 1973 war with Israel.

Jehan said they both always knew of the dangers he faced in signing the peace deal. In an interview with the BBC in 2015, she recalls telling him to wear a bullet proof vest but he refused: “He never cared for his safety.”

Jehan was just 46 when her husband was killed. She spent her remaining years trying to preserve his legacy of peace through her work lecturing around the world.

“Peace. This word, this idea – this goal – is the defining theme of my life. I am always hoping and praying for peace,” she wrote, 12 years before her death.