IMAGE SOURCE REUTERS image caption Wildfires have been burning in Greece in recent days

The study is by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change – a UN group that looked at more than 14,000 scientific papers.

It will be the most up-to-date assessment of how global warming will change the world in the coming decades.

Scientists say it will likely be bad news – but with “nuggets of optimism”.

And environmental experts have said it will be a “massive wake-up call” to governments to cut emissions.

The last time the IPCC looked at the science of global warming was in 2013 – and scientists believe they have learnt a lot since then.

Some papers studied by the panel show that some of the changes humans are inadvertently making to the climate will not be reversed for hundreds or maybe thousands of years.

The IPCC’s findings – which will be revealed at a press conference at 09:00 BST – will also be used during a major summit hosted by the UK in November.

The summit, COP26, which is run by the UN, is seen as a critical moment if climate change is going to be brought under control. Leaders from 196 countries will meet to try and agree action.

Alok Sharma, the UK minister who is leading the summit, said at the weekend that the world was almost running out of time to avoid catastrophe – and the effects of climate change were already happening.

The intergovernmental panel brings together representatives of world governments who appraise research by scientists. That means all governments buy into the findings.

Previously, for instance, they were reluctant to ascribe extreme events such as heatwaves and torrential rain to being at least partly down to climate change.

Now in the case of the heatdome in the US in June, they’re confident to say it would have been almost impossible without climate change.

They say the world will continue to get hotter.

It will also – especially in northern Europe – get wetter, though droughts will increase too as weather patterns shifts.

The panel studied papers showing that sea level would continue to rise for hundreds or possibly thousands of years because of heat already trapped in the ocean deep.

Prof Piers Forster, an expert in climate change from the University of Leeds, said the report “will be able to say a whole lot more about the extremes we are experiencing today and it will be able to be categoric that our emissions of greenhouse gases are causing them and they are also going to get worse”.

“The report will come with quite a lot of bad news about where we are and where we’re going, but there are going to be nuggets of optimism in there which I think are really good for the climate change negotiations,” he told LBC.

One of the causes for optimism he mentioned was that there is still a chance of keeping global warming to below 1.5 degrees.

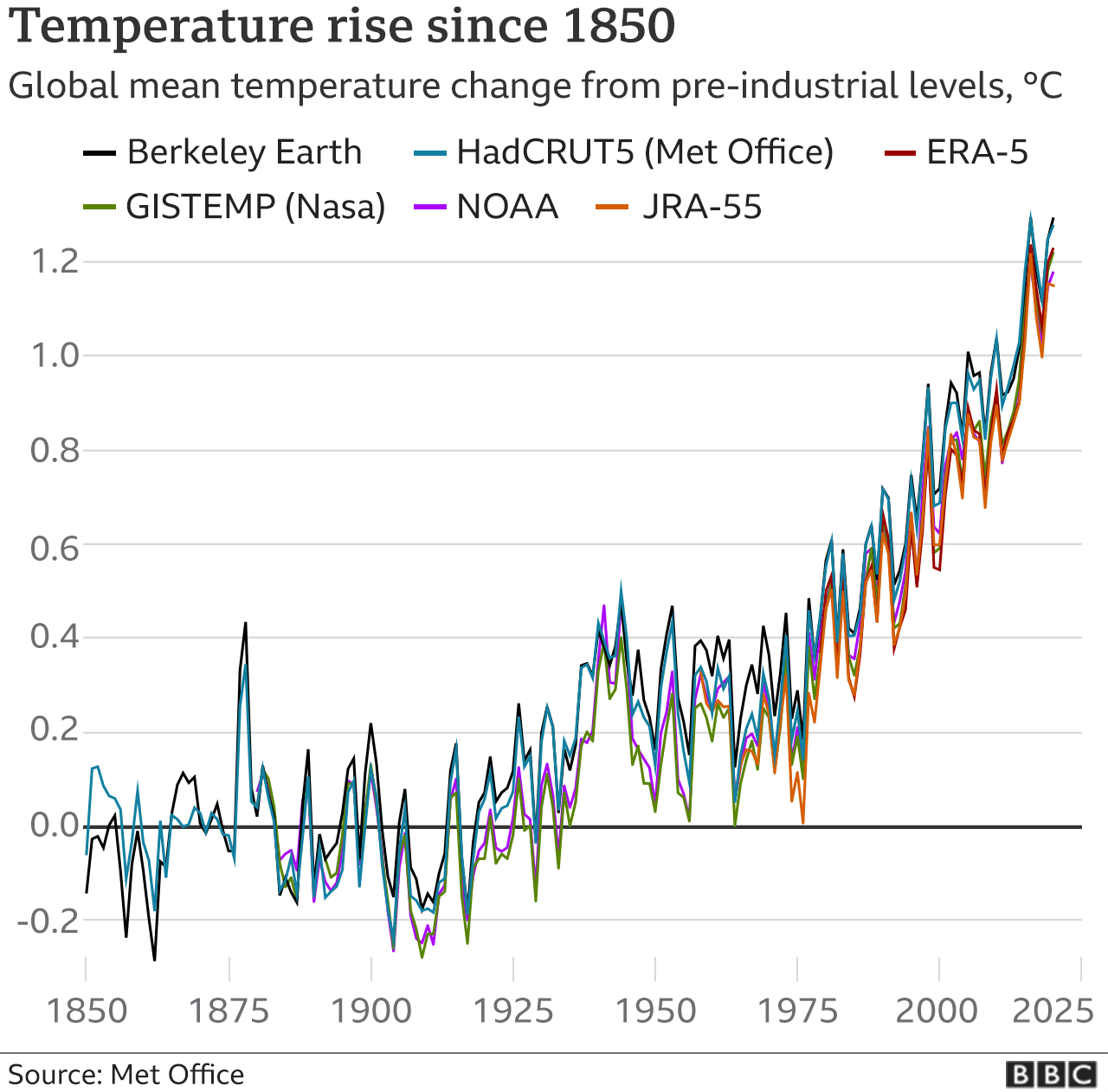

Experts say the impacts of climate change are far more severe when the increase is greater than 1.5C. So far, global temperatures have climbed to 1.2C above pre-industrial levels.

The Paris climate agreement in 2015 established the goal of keeping the increase in the global average temperature to no more than 2C and to try not to surpass 1.5C.

Richard Black, from non-profit advisory group the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit, said: “Coming just before COP26, this report is a massive wake-up call to all those governments that have not yet put forward realistic plans to cut emissions over the next decade.

“It will show that choices made now have a big effect on our future – leading to a runaway world of wild weather impacts and incalculable risks at one end, and at the other a future where climate change is constrained within manageable bounds.”

So, what can we expect from the report?

According to many observers, there have been significant improvements in the science in the last few years.

“Our models have gotten better, we have a better understanding of the physics and the chemistry and the biology, and so they’re able to simulate and project future temperature changes and precipitation changes much better than they were,” said Dr Stephen Cornelius from WWF, an observer at IPCC meetings.

“Another change has been that attribution sciences have increased vastly in the last few years. We can make greater links between climate change and extreme weather events.”

As well as updates on temperature projections, there will likely be a strong focus on the question of humanity’s role in creating the climate crisis.

In the last report in 2013, the IPCC said that humans were the “dominant cause” of global warming since the 1950s.

The message in the latest report is expected to be even stronger, with warnings of how soon global temperatures could rise 1.5C above pre-industrial levels. Experts say the impacts of climate change are far more severe when the increase is greater than 1.5C.

It is expected that this time the IPCC will also outline just how much of an influence humans are having on the oceans, the atmosphere and other aspects of our planetary systems.

One of the most important questions concerns sea-level rise. This has long been a controversial issue for the IPCC, with their previous projections scorned by some scientists as far too conservative.

“In the past they have been so reluctant to give a plausible upper limit on sea-level rise, and we hope that they finally come around this time,” said Prof Arthur Petersen, from UCL in London.

As the world has experienced a series of devastating fires and floods in recent months that have been linked to climate change, the report will also include a new chapter linking extreme weather events to rising temperatures.

What is the IPCC?

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change is a UN body set up in 1988 to assess the science around climate change.

The IPCC provides governments with scientific information they can use to develop policies on global heating.

The first of its comprehensive Assessment Reports on climate change was released in 1992. The sixth in this series will be split into four volumes, the first of which – covering the physical science behind climate change – will be published on Monday. Further parts of the review will cover impacts and solutions.

A summary has been approved in a process involving scientists and representatives of 195 governments.