IMAGE SOURCE AFP

By Paul Melly

Africa analyst

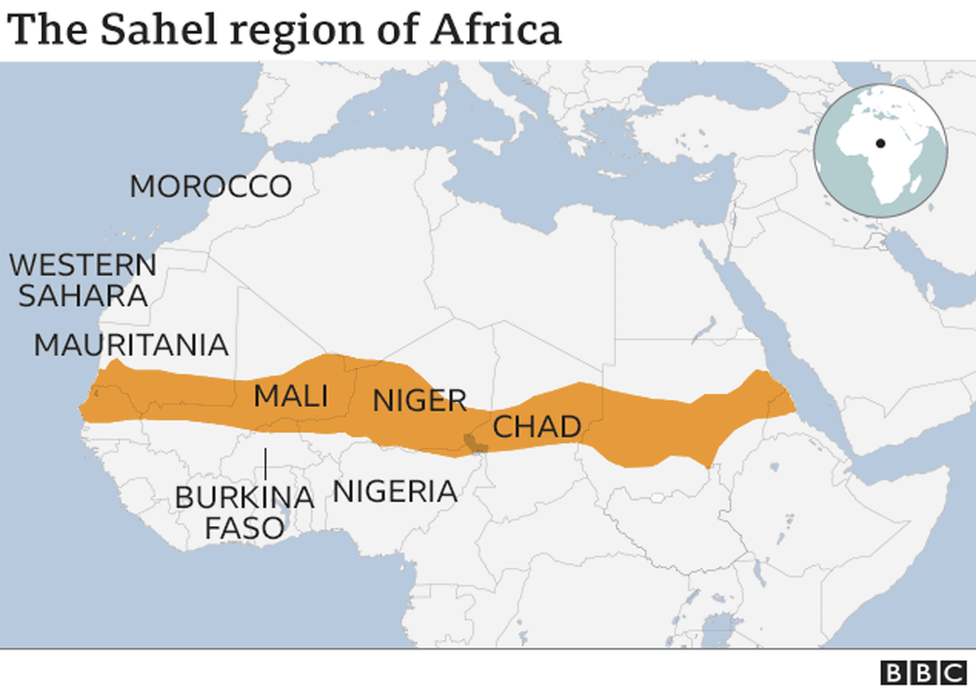

Defence ministers from the G5 Sahel countries – Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania and Niger – are planning more joint military operations and greater “hearts and minds” engagement.

This will target the farming and livestock herding communities of the “three-border region”, where Burkina, Niger and Mali converge and militant activity is at its most intense.

In finalising the new approach at defence talks this week in the Nigérien capital Niamey, the G5 nations are taking the strategic lead.

France is stepping back into a support role, after President Emmanuel Macron recently announced that its counter-terrorism Operation Barkhane was coming to an end with French troop numbers in the Sahel being cut from 5,100 to 2,500-3,000 over the next few months.

More immediately Niger, Mali and Burkina have had to take account of Chad’s abrupt decision in August to reduce its force in the three borders region from 1,200 troops to just 600.

These include:

- Nigeria-based Boko Haram and its off-shoot group Iswap, which continue to raid communities on the shores of Lake Chad

- The overspill impacts of conflict between rebels and government in the neighbouring Central African Republic.

- And in the desert north of Chad itself, homegrown insurgents who may still threaten – despite government efforts to agree frontier security arrangements with Libya.

But while the N’Djamena junta’s choice of priorities is entirely understandable, where does that leave the struggle against the jihadists in the central Sahel?

Motorbikes massacres

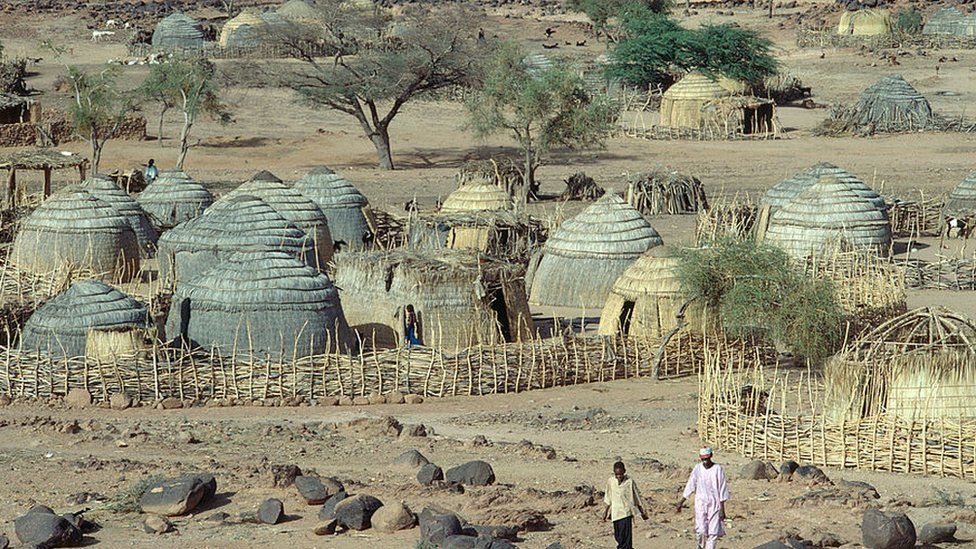

Human Rights Watch estimates that 420 civilians have been killed this year in western Niger alone.

Recent attacks have been typical.

On 16 August gunman on motorbikes burst into the village of Dareye-Daye, which had already been raided in March, and massacred 37 people.

But in fact the Chadian troops that have just been withdrawn were largely equipped with heavy artillery and tracked armoured vehicles – impressive hardware but ill-suited to the highly mobile conflict in the central Sahel, where the June-September wet season renders many zones impassable.

The contingent was only despatched to the central Sahel in February by the late President Déby.

France repeatedly pressed him to contribute to the G5 Sahel “joint force” – an arrangement under which member states’ forces collaborate and operate across borders in the fight against jihadist groups.

The Chadian deployment was originally planned for last year – but was then delayed while Déby concentrated his fire nearer home, fighting Boko Haram.

Once that offensive had been completed, he was happy to play the role of valued emergency ally – a stance that enhanced his regional profile and earned goodwill in Paris, sparing him from overt French pressure over his authoritarian rule at home.

IMAGE SOURCE AFP

IMAGE SOURCE AFPBut by the time Chadian armoured units finally reached the three borders region, the tactical needs of the struggle there were already changing.

Elements of the Malian army, for example, were switching to motorbikes to chase after the fast-moving jihadist bands.

So the Chadians’ departure may not be too harmful for the new G5 strategic effort – and the 600 Chadian soldiers who remain in the area will still contribute.

EU force to take on prominent role

Adjusting to the reduction in France’s military role is more crucial.

Mr Macron has for months faced domestic political questions over his long-term strategic goals in the Sahel.

When on the eve of the G7 summit in June he announced that Operation Barkhane would end, he stressed that France would still maintain a substantial presence in the region.

IMAGE SOURCE GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE GETTY IMAGESThe details followed on 9 July, in a joint press conference with Niger’s recently elected President Mohamed Bazoum.

Europe’s Force Takuba, which was set up last year and operates in close partnership with the Malian army, is to take a more prominent role.

A substantial extra French contingent is being absorbed into Force Takuba – which already consists of several hundred French, Estonian, Czech, Swedish and Italian special forces, with their own helicopters.

Romania has promised troops and there are hopes that other countries will decide to contribute too.

Based in Niamey, Takuba will focus on the three borders, working in support of the G5 armies.

France will keep a small distinct force for specialist counter-terrorist missions and will also remain a major contributor to the European Union mission that helps to train Sahelian armies.

Moreover, French bases in Ivory Coast and Senegal will be maintained, because of real concern about jihadist efforts to infiltrate the countries on the West African coast.

But both G5 governments and France recognise that development and basic service provision, to improve the lives of people across the Sahel, must also be a crucial part of the picture.

Numerous European donors now prioritise the region in their development spending.

However, the challenge is to translate money and grand plans into practical services and projects benefitting local people.

And the military forces of Burkina, Niger and Mali, with Western allies, need to gradually rebuild the security that can allow everyday economic life and development efforts to move forward in greater security.

Paul Melly is a Consulting Fellow with the Africa Programme at Chatham House in London.