IMAGE SOURCE, GETTY IMAGES Image caption, China’s Belt and Road strategy has extended into the Western Balkans, including here in Montenegro

By Jessica Parker

BBC Brussels correspondent

Insiders say it’ll set out “concrete” ideas on digital, transport, climate and energy schemes.

It’s regarded as part of the West’s efforts to counter Chinese influence in Africa and elsewhere.

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen will present the “Global Gateway” initiative on Wednesday.

The EU is looking at how it can leverage billions of euros, drawn from member states, financial institutions and the private sector.

Mrs von der Leyen said in her State of the Union speech in September: “We want investments in quality infrastructure, connecting goods, people and services around the world.”

But Andrew Small, a Senior Transatlantic Fellow at the German Marshall Fund, says the backdrop is inescapable: “Global Gateway wouldn’t exist if you didn’t have Belt and Road.”

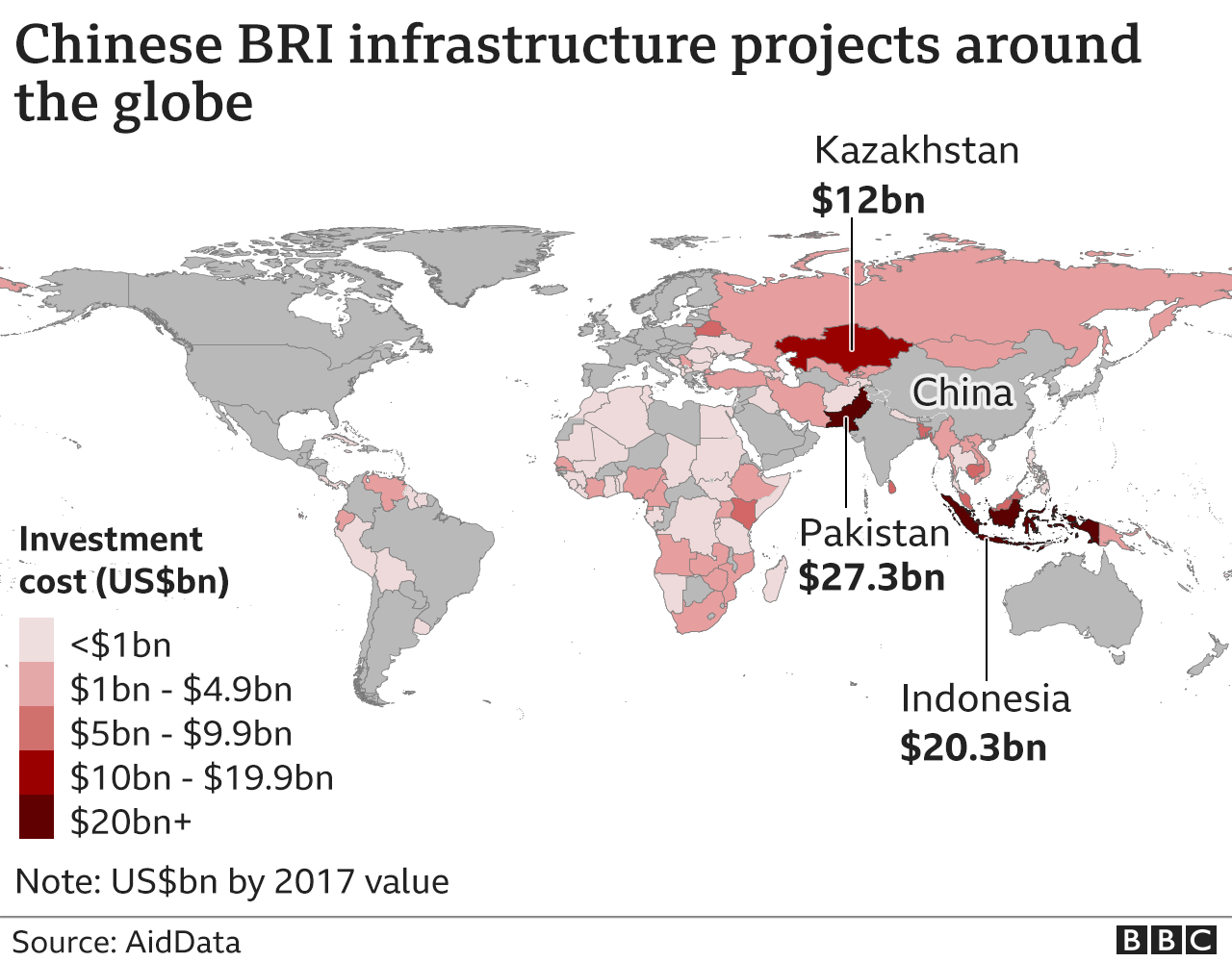

Belt and Road has been a centre-piece of Chinese foreign policy; developing trade links by ploughing money into new roads, ports, railways and bridges.

The strategy has reached into Asia, the Indo-Pacific, Africa and even into the EU’s nearer neighbours in the Western Balkans.

It has been criticised as a means of providing “predatory loans” in what is labelled “debt-trap diplomacy”.

Either way, China’s economic and geopolitical footprint has grown as tensions rise with the West.

Now the EU will attempt to marshal its own clout and resources, in what Andrew Small says will be a big test.

The question is whether the EU can really act in this geo-political space.

“Or is it too rigid, too bogged down by internal bureaucratic fighting? If they fail at this, it’s a big miss,” he argues.

One diplomat told me, “It’s a good sign that finally Europe is asserting its influence in this area.”

But a common interest could also create more competition, according to Scott Morris, a Senior Fellow at the Center for Global Development.

After all, the US has its own “Build Back Better World” initiative launched at the G7 last June. “This is a noisy space with a lot of brands bumping into each other,” says Mr Morris.

However he’s “hopeful” of success for the Global Gateway initiative. He says, “more importantly” than rivalling China, it’s a chance for Europe to “achieve a scale of financing that can do some good in developing countries that need some capital”.

Once the EU plan is approved by the College of Commissioners on Wednesday it will be presented by Ursula von der Leyen.

The EU has pointedly emphasised its “values-based” and “transparent” approach, arguing it wants to create links not dependencies.

But this is also about influence, as the Commission continues to look for ways to flex its muscles on the geopolitical stage and, in turn, find out how strong those muscles are.